Following the National Day Rally speech, there seems to be some confusion regarding the announcement that companies in Singapore will be required to pay local citizen/PR employees a minimum of S$1,400 per month.

Judging by public comments online, many people appear to be cheering it as an introduction of national minimum wage for all Singaporeans. This is incorrect.

In reality, not only is it not a minimum wage, but it has existed in Singapore for years and its purpose is quite different.

What Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong was referring to is Local Qualifying Salary (LQS) — a solution meant to counteract abuse of employment of foreign workers at the expense of Singaporeans.

It applies only to companies that want to employ foreigners by ensuring that a minimum number of Singaporeans find employment there first and with a sufficiently high minimum salary, which is set by the LQS.

It’s only after the quota of properly paid Singaporeans is reached, can the companies employ foreigners (particularly with a higher paid S-Pass rather than a work permit).

Here’s an overview of various measures meant to regulate foreign workforce in Singapore over the past five years and the role LQS plays among them:

LQS was put in place to ensure that the laws are not gamed by dishonest employers trying to gain access to cheap foreign labour.

It’s easy to imagine how they could dodge the laws simply by paying a few hundred dollars to ghost stand-in “employees” (friends or family) just to fill the necessary quota enabling them to employ foreigners, without actually providing employment to locals.

This minimum salary requirement is meant to encourage creation of real jobs for the poorest Singaporeans before the employer can hire any foreigners.

After the latest revisions, minimum LQS level was already raised from S$1,000 in 2016 by about S$100 per year, to S$1,400 in 2020.

However, until now, it also offered an additional tier of S$700 to S$1,400, which would count as 0.5 local employee. For instance, if a company employed two Singaporeans at say S$1,000 per month, it would count (for its quota determining how many foreign workers it can employ) as one employed Singaporean.

With yesterday’s announcement, the part marked in yellow is going away and S$1,400 will be the absolute minimum for all employees.

So while it’s not a minimum wage as such, it serves to:

- Protect the poorest Singaporeans

- Guarantee employment for locals ahead of cheap foreign labour

- Ensure a minimum salary for Singaporeans employed by companies wishing to tap foreign workers

Protecting Singaporeans and Singaporean companies alike

Depending on the industry, there are different limits of maximum dependency on foreign workers holding S-passes and basic work permits. For manufacturing, construction, process and marine shipyards, these levels may seem very high at 60 to 87.5 per cent of total workforce.

But only 18 to 20 per cent of those employed can work at the S-Pass level, with a minimum salary of S$2,500 and levies — what is going to be cut to 15 per cent from 1 January 2023. Nearly every other foreign worker would carry just a basic work permit and be among the lowest-paid in the company (with a pay no Singaporean would accept).

These regulations are meant to ensure that mid and higher tier employees are largely local, while business owners are allowed greater flexibility at the low-end, in jobs that Singaporeans wouldn’t take due to very low pay.

In other words, the system not only seeks to protect local employment but also provides gradual incentives to hire Singaporeans in increasingly better paid and more responsible jobs.

At the same time, it allows for an influx of very cheap labour to perform menial tasks that there’s a lack of local workforce for, thus increasing the productivity of Singaporean companies, while keeping costs relatively low and productivity high.

On top of that, through a fairly complex system of levies, it permits the government to draw billions of dollars every year from the gaps between low employment costs of foreigners versus high employment costs of locals, while still keeping overall labour expenses low enough for Singaporean businesses.

It’s a form of taxation on foreign employment that provides healthy revenues to the national budget while being another tool used to fine-tune the local labour market, encouraging or discouraging influx of workers from abroad in specific industries.

A more sophisticated system

Given the complexity of the above, it should now be quite understandable why the local government resists the calls to implement a blanket, nationwide minimum wage. It is simply a much more antiquated solution than what Singapore already employs.

Judging by public comments, many people seem to erroneously believe that the city-state — being ranked as the most business-friendly country in the world — is some sort of a capitalistic free-for-all.

The reality is however, that Singapore is easy and straightforward where it needs to be, and very precisely regulated in areas that may have a negative impact on the society.

While populists in the West tend to pit workers against business owners, Singapore recognises that the needs of both sides have to be addressed — both by dialogue and careful, custom-tailored and adjustable legislation — for the whole country to keep growing.

“You make profit a dirty word and Singapore dies,” remarked Lee Kuan Yew 40 years ago. Businesses driven to make money is what makes economy flourish, for the benefit of all. That said, this drive cannot get out of hand and happen at the expense of workers that contribute to it.

A thoughtless, blanket minimum wage would upset not only many foreign corporations (in fact, it would likely matter least to them as they tend to operate in more developed industries) but chiefly, many domestic small, family businesses which would be forced to deal with burdensome bureaucracy when having friends or relatives perform services for them or employing help on an ad hoc basis.

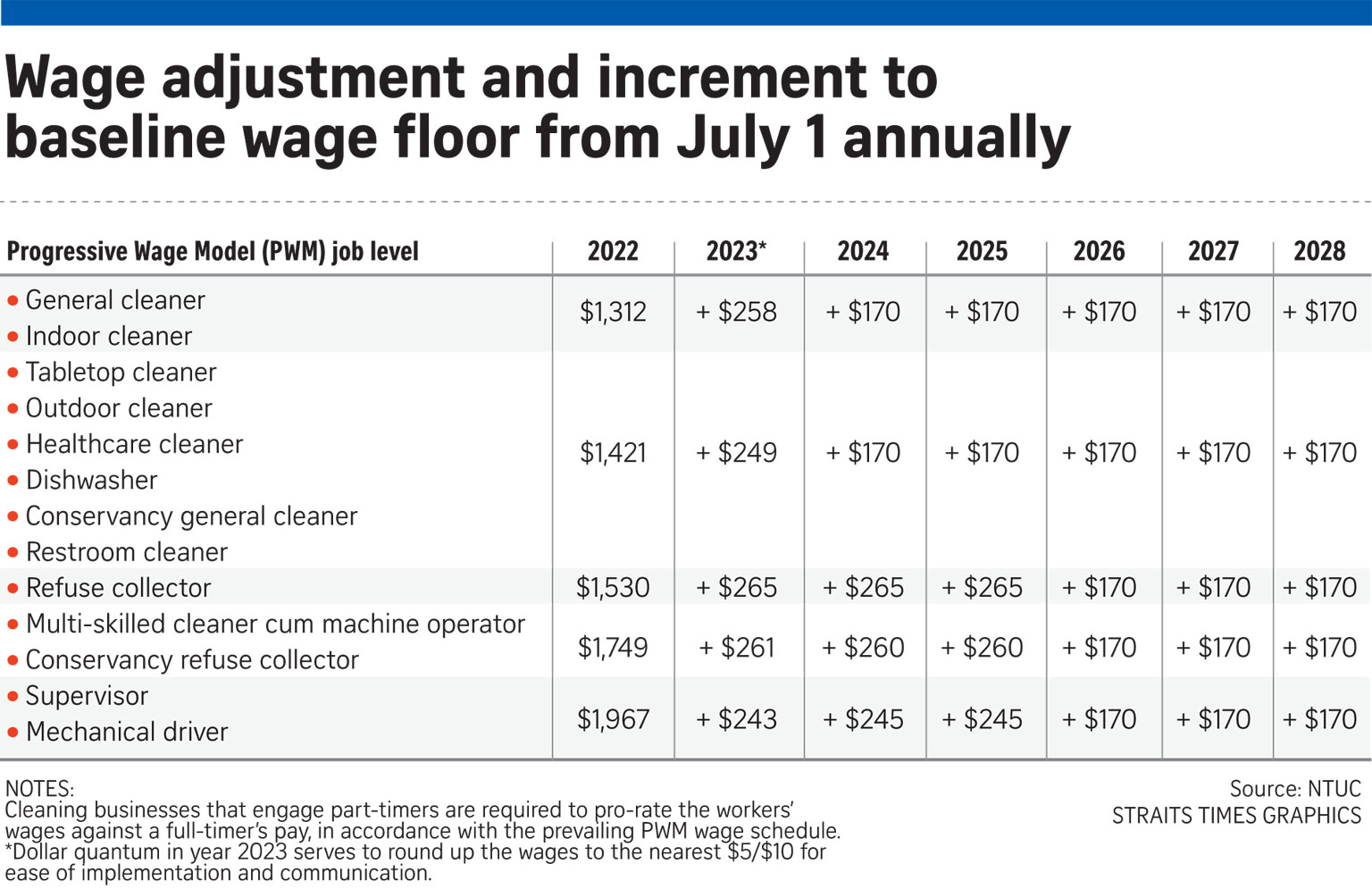

At the same time, there are targeted solutions like Progressive Minimum Wage (PMW) — which is going to now be expanded into new industries — focused on larger companies and professions which do not have a clear career progress path, like in cleaning or security, and could leave people relatively more impoverished as time goes by.

PMW not only sets the minimum wage floor for the most vulnerable jobs. It actually provides a career plan leading to much higher salaries than a typical minimum wage would guarantee, helping those down at the bottom not only secure a liveable basic salary, but actually climb the ladder with time.

Both PMW and LQS are just some of the tools in a highly developed, precise system of rules, levies, quotas and ceilings covering various sectors of the economy.

They aim to provide a healthy balance, guaranteeing easy access to meaningful employment to all willing locals, while allowing companies a deal of flexibility in hiring foreign workers to fill the gaps they need to have filled to remain globally competitive and keep entire Singapore growing.

Featured Image Credit: Prime Minister’s Office