As 136 countries — Singapore included — have signed a landmark agreement establishing a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15 per cent, there’s doubt as to how it is going to affect the city-state.

After all, small business havens like Singapore are the primary target of this global deal, in an effort by governments all over the world to force corporations to pay more in taxes and curb their ability to avoid it through complicated foreign, offshore mechanisms.

Earlier in July, Minister of Finance Lawrence Wong responded to questions in the parliament that the deal will make it harder for Singapore to attract investments.

But is it really?

In his responses, he mentioned the necessity for the city to compete qualitatively, by offering better business conditions, better workforce, infrastructure etc.

The thing is, Singapore is already doing that and has done it for time immemorial.

Perhaps then, Minister Wong’s statements were just a public show of concern ahead of finalisation of the deal which, in reality, is going to benefit Singapore more than it can hurt it.

Making MNCs pay their ‘fair share’

Isn’t Singapore going to lose some tax revenue to other countries?

Let’s start with the first of the two pillars of the agreement, which is aimed at the world’s largest corporations like Google, Amazon or Apple.

Critics may point out the specific provisions of the document, that are supposed to force large MNCs to pay taxes where their revenues come from.

On the face of it, then, it seems that Singapore — and other small countries — would stand to lose a lot of money. After all, the local market is tiny and all large businesses headquartered here make most of their sales abroad.

If they are forced to pay taxes where they make sales, shouldn’t the city-state brace for tough times?

No. When you read the fine print, it becomes clear that this rule is pretty much dead on arrival, as it applies to strictly defined businesses, whose:

- Global sales are over 20 billion euros

- Profit margins are above 10 per cent

And once they fulfil these criteria, only 25 per cent of their profits above the 10 per cent margins would be reallocated to national markets outside of their primary locale.

In effect, that is going to end up being a pittance, coming only from a handful of businesses that qualify. Amazon, for example, would not, as its profit margins have never exceeded 10 per cent and are typically within low to mid single digits.

In fact, intensive reinvestment or other ways of minimising profit margins, could easily be used by the largest global corporations to fall outside of the purview of the agreement and avoid the new tax obligations entirely.

What about the second pillar? The global tax floor of 15%? Isn’t that going to hurt Singapore?

The end to corporate tax competition

The main consequence of the second pillar is limitation of corporate tax competition, particularly the “race to the bottom” by some countries hoping to attract foreign businesses to run their operations through their fiscal jurisdiction, helping them to collect a portion of the money that would otherwise be paid somewhere else.

However, again, this does not necessarily apply to Singapore as, contrary to what many seem to believe, it has never actually been a tax haven.

Local corporate tax rate is not low at all. At 17 per cent, it is comparable to many European countries and not much lower than American federal rate of 21 per cent that’s in force since 2018, after president Donald Trump cut it from a whopping 35 per cent.

It’s also considerably higher than 12.5 per cent levied in Ireland, 10 per cent in Bulgaria, or just nine per cent in Hungary — all EU countries no less.

Effective tax rate in the city-state is certainly lower than 17 per cent, due to various incentives — and is likely below the new 15 per cent global floor — but it’s not so far off for the new rules to make a meaningful difference.

Singapore is not the Cayman Islands. It’s not a tax haven as such — it’s a normal country, with a fairly standard tax system and only marginally more attractive rates than elsewhere.

It has other — and far more important — advantages that, collectively, make it so attractive to businesses:

- Low bureaucracy – doing business in Singapore is easy, compared to almost every other jurisdiction in the world.

- Low corruption – there’s no need to worry about the necessity of paying kickbacks to corrupt officials to get anything done.

- Political stability – with a single, business-friendly party in charge of the country, Singapore is safe and predictable over the long term.

- Excellent infrastructure – world-class harbour and airport make it easy to trade with the rest of the world.

- Qualified workforce and fairly attractive immigration policies – no business can operate without the right people.

- Location – finally, all of the above are collected in this small place in the middle of Asia, at the crossroads between the Far East and the West. No other country comes close.

Only after all of these are considered, does taxation come into play — and the authorities have made sure that Singapore’s taxes are as low as they need to be and as high as they can be, so the city-state remains attractive but can also draw benefits from hosting so many foreign companies.

Will international business suddenly turn its back on Singapore even if due to the new global tax rate it will, effectively, be forced to pay a few percentage points more on its income? It’s unlikely.

Ironically, however, establishing such a minimum floor is in Singapore’s interest and it can even lead to an increase in tax revenues, if it is forced to collect more money under the terms of the agreement. Businesses are more likely to pay up and enjoy other benefits than seek any other jurisdiction.

Most importantly, however, it effectively removes the risk of future competition on corporate tax rates — something that the city-state would be more vulnerable to than most developed countries.

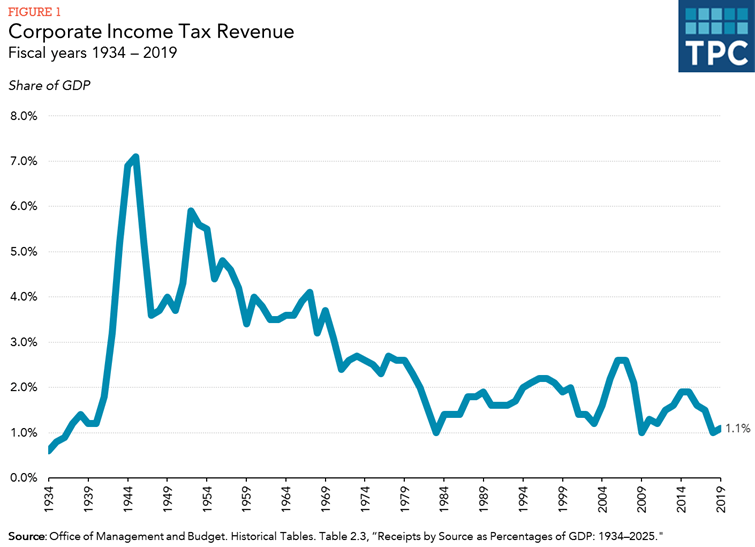

You see, economies of the West don’t actually rely on corporate tax incomes very much. In the US, UK, Germany or France, corporate tax receipts amount to between four and six per cent of their annual budgets — and even less in proportion to GDP (between one and two per cent).

In Singapore, however, the share of corporate taxes is a whopping 23 per cent of operating revenues and over 18 per cent when we factor in the NIRC – and between three to four per cent of the GDP.

If the city-state was pushed into tax rate competition, it could lose billions of dollars each year and slide into a persistent, large deficit.

Paradoxically, Western countries are in a much better position to lower corporate tax rates, or even abolish them entirely.

Dealing with an estimated annual deficit of one to two per cent of GDP (if any of them simply removed the CIT) would not be a problem with a slightly more responsible fiscal management, as they have been running even larger deficits already, even before the pandemic.

For instance, annual federal CIT revenues in the US in recent years have been around US$200 to US$350 billion, while the country kept running deficits of anywhere between US$500 and US$900+ billion. Removing federal corporate taxation would hardly make a major difference.

In reality, the gap would likely be smaller as some of the money would still return in other forms (e.g. through taxes on personal income from higher remuneration of workers or company executives, higher employment, taxation on capital gains thanks to more investment, greater utilisation of financial services and so on).

Also, corporations which have moved trillions of dollars abroad (in the process of tax optimisation) would now repatriate the funds and freely use them domestically, what would likely yield additional economic benefits, and contribute to tax revenues via other channels.

As a result, the net impact of either significantly cutting or outright abolishing corporate taxation in the West would be relatively small and could even end up creating enormous economic benefits.

In other words, the countries most loudly demanding global rules on corporate taxation could easily become tax havens themselves – and at a fairly low cost.

The reason they aren’t going to is not that freezing or raising taxes is in their best interest, but that it’s in the best interest of their politicians, scrambling to find and cement new sources of “revenue” they can keep “bribing” their voters with.

Ironically, if they ever decided to cut corporate tax rates, places like Singapore would really feel the pinch as they would simply not be able to compete due to much higher reliance on revenues they generate for their national budgets.

The greatest threat to Singapore has always been the return of common sense and responsibility in Western governance, which could easily make those large economies far more competitive — and attractive. Fortunately for the city-state, however, they have decided to continue crippling themselves. And now they have even put it in a binding international agreement.

With the new floor set at an effective rate of 15 per cent, Singapore doesn’t have to fear tax competition. And because its key advantages have always been legal, political and institutional, it is bound to be even more — not less — attractive than it is today.

Featured Image Credit: The Conversation