Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

Whenever I read anything anywhere about global demographic crisis manifesting itself in developed countries, which are seeing plummeting fertility rates, it inevitably is portrayed chiefly as an economic crisis — and is treated by governments as such.

We’re being told that, due to rising living costs, people refuse to have more children and so authorities in countries around the world come up with various support packages, spending billions of dollars to encourage families to have more kids.

The result is that it has, thus far, roundly failed everywhere it has been tried.

Show me the money

I really don’t know why anybody would ever have thought that it would work in the first place, since the decision to have or not to have kids has quite little to do with money.

What makes it all even more absurd is that it’s visible to the naked eye.

Ask yourself these questions:

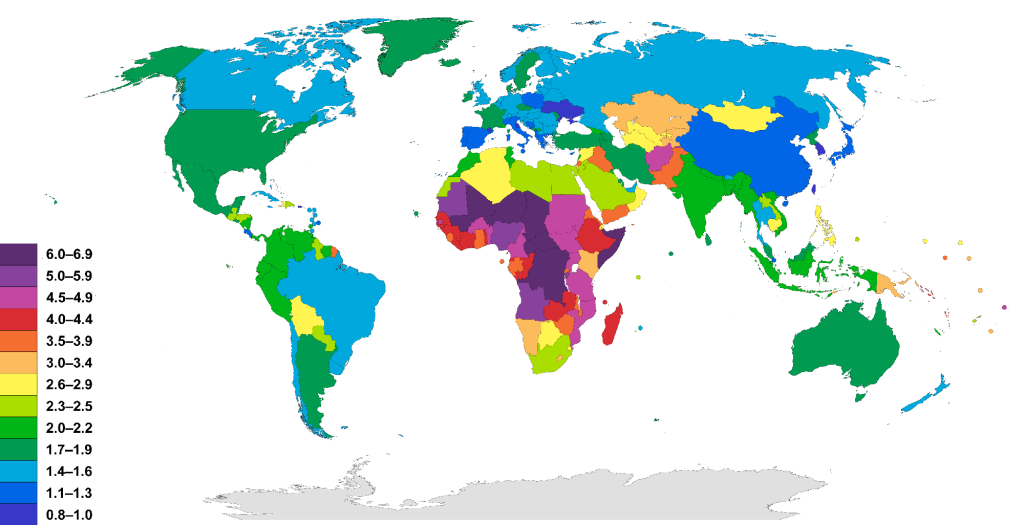

- Where are fertility rates the highest in the world?

- Are wealthy people having the most children?

If fertility rates were significantly affected by economic status, then the answers to these questions should be: “the developed world” and “yes” — but it’s the exact opposite.

We all know that, by far, the most children are born in some of the poorest countries in the world. It is also fact that the poorest families in each respective society tend to be the largest.

And before you jump to tell me that the poor are simply irresponsible, have nothing better to do, are not intelligent enough or can’t afford contraception (or don’t have access to it), please consider how Singaporean households used to look like just a few decades ago.

We hear a lot of complaints about access to appropriate housing, expensive living et cetera but it wasn’t so long ago that many Singaporeans would live in five, six, seven pax or larger households, often in a two- or three-bedroom apartment, while being considerably poorer than they are today.

There was no MRT, many HDBs didn’t even have lifts, and most people were making a few hundred dollars per month. The problem was, in fact, so significant that the authorities ran their now (in)famous campaign of “Stop-at-Two” in the 1970s.

In other words, Singaporeans used to have many children, despite lack of government incentives, much lower economic status, and much poorer housing conditions than they do today.

Secondly, while the richest guy in the world, Elon Musk, has managed to father 10 kids, he’s an outlier among the wealthy.

Again, if living costs were the underlying problem, one would expect that, within the same country, richer people would have more children — but that isn’t the case either.

So, how on Earth did anybody conclude that money is the issue?

Don’t get me wrong, some form of parental support may nudge some to have another child, but nowhere in the world has it been proven to actually solve the problem of low fertility rates.

Western Europe is often presented as an example where social policies may have helped, but it falls apart when you dig into the ethnic background of the most fertile families and discover they comprise mainly impoverished immigrants not locals, while overall TFR keeps going down.

Others point to a few more homogeneous, Eastern European nations, particularly Czechia, as a success story after its rates increased from 1.3 to about 1.8 in the past 20 years — ignoring the fact that it’s still below replacement levels and the country remains dependent on inflow of immigrants for a boost to local resident figures.

Sure, 1.8 may sound like a world of difference compared to Singapore’s 1.05 (or South Korea’s dismal 0.78, the lowest in the world) but you have to bear in mind that this region of EU is still much less wealthy and nowhere near as urbanised as both Western EU and most developed nations of East and Southeast Asia, which are facing the biggest problems.

So, again, is it really about the money?

And if it isn’t, then what is it about after all?

Managing expectations

Plummeting fertility rates are a universal problem of all developed, wealthy societies. In fact, few things are stronger than the inverse correlation between wealth and fertility, which transcends borders, ethnicity and culture.

Every country in the world used to have large households in its impoverished past, which rapidly shrank as it has grown richer.

But you may ask – what about those surveys in Singapore which are showing that 80 per cent of Singaporeans want to marry and 77 per cent want to have children, preferably two or more!?

“Of those who were married, a vast majority — 92 per cent — indicated that they wanted to have two or more children, similar to the past surveys conducted in 2016 and 2012.”

– Straits Times

92 per cent! How can it be then, that the TFR is so low? Is it about BTO delays? Rising resale HDB prices? Plate of chicken rice going up?

No, it’s about expectations we all have about life.

Having children isn’t only about the money but, primarily, time.

Sure, when you have a bit more in the bank, you are able to pay for maids and babysitters but these services can’t replace all — or even most — of your responsibilities as a parent.

When you ask people what they would want, they will tell you their dreams. But when reality hits, few want to give up most of their lives for two decades to cater to the needs of growing kids. Yes, they would like to have two or more — but they also want a good job, lovely holidays, concerts, dinners with friends and so on.

Women used to be stay-at-home full-time moms, but now the majority wants to pursue a career — and a successful one, at that. There’s an expectation that you can have it all — a family, professional success, frequent holidays and the ability to look great at the same time.

Something’s gotta give. Plus, we have to deal with a lot more distractions than our parents.

Life is easier today than it was before, and we are all richer than our predecessors were — but there are many more things competing for our attention and wallets.

Shopping, travel, fine dining, entertainment, electronic gadgetry, endless competition to look better, prettier, more successful on social media – and so on.

You can’t have it all to the full, so most people settle for one, at most two children (rarely) to tick the “family” box and move on to other things.

Breathing room

Besides time, another issue is space.

As I mentioned before, people used to have lower expectations about their housing. Five or six people could occupy a fairly small flat. Today, every child has to have their own bedroom.

It’s not that HDB apartments have shrunk or become less affordable in proportion to income (they haven’t), but people’s expectations have vastly outgrown them.

Even five-room flats typically have just three bedrooms. Today, this means that you can comfortably house just two kids (parental bedroom + two for the children), despite having over 1,000 square feet of space.

Even if it was subdivided to create another room or two, owners would have to give up something — like a study, store room or a walk-in wardrobe that they have grown used to.

To house as many kids as their parents or grandparents did, everybody would now have to occupy a large bungalow, simply because modern expectations of living comforts have grown so much.

If you don’t believe me, just look at what happened to the housing market during the pandemic.

As the reality of work from home kicked in — which was really just spending a few hours more in your apartment, hardly the end of the world — demand for housing surged, with prices following.

All of a sudden, thousands have realised they want more space to do as little as work from their laptops.

Being forced to share it with your family — even a small one — during office hours, proved to be enough of an incentive to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on an upgrade.

Do you think a few thousand bucks from the government, longer maternal leave and some childcare perks stand a chance to make any impact in such a reality?

Paradoxically, then, people used to have more kids when their expectations were lower. When there was less to do, less to aspire to, less to show off to your social circles.

It would also explain why even in those shrinking, developed countries it’s the poorest who still have the most offspring — because their aspirations and ambitions outside of family life are lower too.

It’s not money but simpler life that large families sprout on.

But I don’t think most people would be willing to accept it, so demographic problems — in Singapore and elsewhere — are unlikely to be fixed, no matter how much is spent.

Featured Image Credit: SmartParents

Also Read: How costly are resale HDB really? One chart combines all transactions to give you the answer