Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

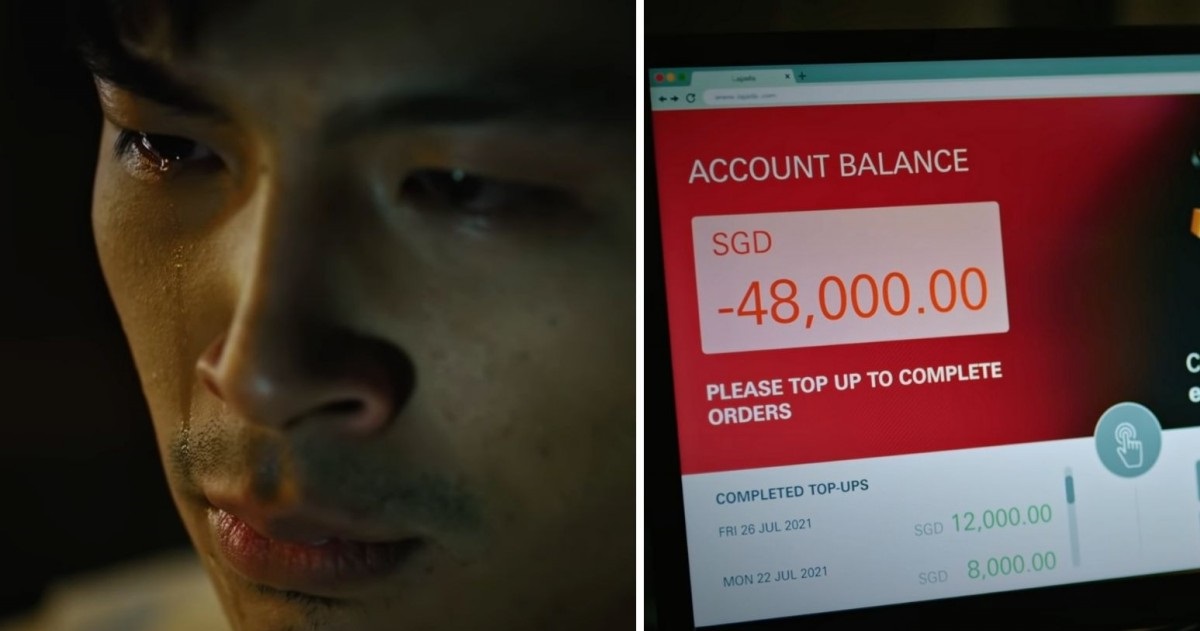

Scams have been making the headlines quite frequently in recent months.

First, there was a phishing scam that targeted OCBC customers. Just a few months later, there was another one that targeted DBS customers instead.

In general, scams are becoming more commonplace — 2021 saw a 24 per cent increase in reported cases as compared to 2020, and while rates for other crimes declined overall, the increase in scams was so significant that Singapore’s overall crime levels drove up.

Even celebrities have not been spared — Singaporean rapper Yung Raja lost almost S$100,000 to an NFT scam earlier this year.

The increasing number of affected Singaporeans, as well as the high-profile targets, have caused quite the outcry.

In response, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has announced that a framework for the equitable sharing of losses arising from scams is on the way.

In the meantime, the Association of Banks in Singapore has also put in place new guidelines in an attempt to try and reduce the amounts lost to scams. OCBC has even gone as far as to give customers access to a kill switch to freeze their accounts if they suspect that they have been scammed.

However, not everyone is satisfied. In particular, some have called for banks to bear all the losses from such scams, meaning that Singaporeans who fall victim to the scams should be compensated fully for the amount that they have lost.

Why should banks bear the losses?

For many consumers, this may seem fair. One of the reasons why consumers put money in banks is to keep their funds secure, so security is of course, one of the main responsibilities of the banks.

When scams occur and banks release funds into the possession of scammers, there is a case to be made that the banks have failed in this duty — they have failed to keep our funds safe, and the resulting loss should not accrue to the consumer, but to the service provider, which in this case is the bank. The scam therefore reflects an underinvestment in security on the bank’s part.

Certainly, if banks fail to adequately ensure the security of their customers’ funds, why should customers be held responsible when these funds are stolen? Instead, customers should be made whole, with banks compensating losses to customers due to their security oversights.

But at the same time, we should also consider that banks have been putting up greater security measures in an effort to prevent scams. So is it really true that banks are underinvesting in their digital security measures?

There are already several levels of verification that customers have to go through in order to access their accounts, and scammers also have to go through them in order to fraudulently transfer funds.

This means that scammers must first obtain the credentials of customers in order to access their accounts. If customers safeguard their own credentials properly, scammers would theoretically be unable to transfer any money out.

As such, customers must share some blame for the scams as well. No amount of infrastructure can guard against a lack of vigilance.

On top of this, there is a limit as to how much banks can increase security before it becomes a hassle. There will only be so much hassle that customers are willing to take before the alternative becomes preferable, a return to physical banking.

And lest we forget, scams also exist for physical banking. There will always be a cat-and-mouse game between scammers and banking security, whether it is online or offline.

While it is also true that making banks responsible for losses will likely incentivise them to invest in security, we must remember that when the only tool we have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.

Better ways to deal with scams need to be found, instead of simply hammering away with the one tool that we have.

Incentives and moral hazard arguments must be applied fairly

Some have also argued that if consumers share losses with banks, banks will simply find ways to shift the blame to consumers in an effort to reduce their own liability and losses.

This is certainly cause for concern. American insurance companies have come under the spotlight in popular culture for their willingness to play the blame game in an effort to reduce the amounts that they pay to customers.

If banks in Singapore were to do the same, it would be to the detriment of customers if they lose money to scams and banks refuse to accept any responsibility.

But to suggest the same situation would arise in Singapore simply because banks can blame consumers for their losses is ridiculous. As the saying goes, just because you can, doesn’t always mean you should.

Banks remain profit-driven institutions — they rely on customers to deposit funds, in order to reinvest these deposits for profit and pay customers’ interest payments. The difference is pocketed as profit.

While we may consider banks monolithic, uncaring entities in a country of cold, calculating efficiency, banks are ultimately still subject to competition with each other — offering better savings plans, interest rates, and terms of use.

For a bank to simply blame customers when they get scammed would mean harming their long term profits when consumers recognise the pattern of behaviour and switch to a different bank.

Unnecessary blame-shifting, therefore, would be a strategic business error on the part of the banks, and likely a fatal one.

Banks in Singapore have already shown that they are willing to take lower profits in order to compensate victims, even when the banks may not be entirely at fault. OCBC offered a one-time payout for scam victims, fully covering any losses from the phishing scam.

As MAS and OCBC have noted, this was a one-off payout that should not indicate how future scam losses should be settled.

The payout already sets a dangerous precedent. If consumers know that banks will cover their losses, there really is no incentive for them to remain vigilant.

Even though there may be lengthy investigations into the veracity of their claims of being scammed, customers will still get their money back at the end of the day, while banks suffer the loss on the customers’ behalf.

The cost of lax vigilance, therefore, is not placed where it should be, and it is of utmost importance that the cost is placed where it belongs.

The argument that there is a moral hazard in loss sharing cuts both ways — if we assume that moral hazard will exist for banks when they are able to offload blame onto customers, we must also assume moral hazard for customers who are secure in the knowledge that they will not suffer for their own lapses.

The way forward must therefore be one that constrains this moral hazard as much as possible, but forcing banks to bear all the losses from scams is definitely not a solution that satisfies this condition.

Is blame-shifting really something to be avoided at all costs?

While it may seem that blame-shifting is something that is inherently bad, it really should not be considered as such. In many cases, blame-shifting is necessary, and when dealing with how to equitably share losses from scams, it may actually work as a force for good.

In a court of law, lawyers present the best case for their clients — the case which presents their clients as fault-free as possible and shifts as much blame as possible to another party.

This is, ultimately, how the legal system works — it works on the strength of arguments to ensure that judgements are fair.

Blame shifting, therefore, is part of the game, within limits. Lawyers present the best case, but cannot present a false case, one that is not true.

What is to be avoided is excessive blame-shifting, and banks are already incentivised to avoid this.

Banks are already facing an unwinnable uphill battle and running lower profits in order to compensate victims and investigate claims. As consumers, while the pain of losing our hard-earned money is something that we wish to avoid, we should ultimately recognise that more often than not, we may have a part to play in causing the loss in the first place.

When banks bear all the losses, consumers have almost nothing to lose from their carelessness and this is an unfair scenario. While banks do their best to protect us, we must also do our part to protect ourselves.

At the end of the day, the banks are not the enemies of consumers — we both have a shared interest in protecting our property from those who would hope to unfairly acquire it.

But when our efforts fail, it is only right that an equitable sharing of losses is reached — one that encourages all parties to do better in the future.

Featured Image Credit: The Drum