[Update, 22 Oct 2018] Equatorial Space Industries has won the first prize in the MBRSC Innovation Challenge at this year’s GITEX Future Stars. Held in Dubai, the Singapore startup was one of 15 international teams that competed. They eventually emerged as the winner by the the jury from Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC), and walked away with US$30,000.

Said Simon Gwozdz, CEO of Equatorial Space Industries, “We are thrilled to have gotten the grand prize – not only because it will massively speed up our prototyping, but also open up possible collaboration opportunities with the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre, especially on their ambitious Mars 2117 Initiative. We couldn’t be more honored and hope it will be first of many great things to come in the near future.”

–

We all know Elon Musk for many reasons.

We know him as the co-founder and CEO of Tesla Inc.

Not just giving us some serious eyecandy with its sleek lineup of cars, Musk has also been pushing the frontiers of the way we drive cars; from its fully electric fleet to Autopilot, which looks to open us up to a future of self-driving vehicles.

We also know him as the founder of SpaceX, and, in a way, the enabler of space travel and exploration dreams.

Fascinated by space and life on other planets, Musk came up with Mars Oasis in 2011, a project which aimed to land a miniature experimental greenhouse on Mars.

The greenhouse was to grow samples of food crops in an enclosed chamber filled with treated Martian regolith (soil), to test the feasibility of humans living off the largely unexplored planet.

“The first life on Mars, as far as we know, and the farthest that life’s ever travelled,” he enthused in an interview with Wired.

But he soon ran into a roadblock – one that eventually became the definitive reason for SpaceX’s existence.

“I started to price it out,” he continued in the interview.

“The spacecraft, the communications, the greenhouse experiment: I figured out how to do all that for relatively little. But then came the rocket – the actual propulsion from Earth to Mars.”

The cheapest US rocket that could make the journey cost US$65 million, and, needing two, the project would set him back US$130 million.

Including everything else involved in Mars Oasis and the potential overrunning of costs, Musk knew he wasn’t able to cover it.

Of course, that wasn’t going to stop him.

He travelled to Moscow, Russia, with aerospace suppliers fixer Jim Cantrell and founder of The Founder Institute (also Musk’s best friend from college) Adeo Ressi, to look for refurbished intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) – “Without the nukes, obviously” – as an alternative.

After several failed meetings from 2001 to 2002, they met again with ISC Kosmotras, which offered the group one rocket for US$8 million.

This was deemed too expensive, and once again, the trio returned to the US empty-handed.

On the plane ride back, Musk had an epiphany – instead being subject to exorbitant prices, why not start a company and build his own affordable rockets?

With that, SpaceX was launched (pun not intended) in 2002.

Having graduated with a Physics and Economics degree, Musk relooked at the process of building a rocket from the standpoint of a physicist, and not a rocket scientist.

He then found out that the cost of the materials typically used in construction was just “around two percent of the typical price [of a rocket,] which is a crazy ratio for a large mechanical product”.

Six years later, in 2008, SpaceX successfully launched its first rocket, Falcon 1, into orbit around the Earth.

This was its 4th attempt, since its first launch in March 2006.

The Falcon 1 was launched a total of five times in its 3-year career, with its swansong seeing it successfully delivering the Malaysian RazakSAT satellite to orbit in July 2009.

Since then, SpaceX has continued to achieve milestones in spacetech.

It was the only private company to return a spacecraft from low-Earth orbit in December 2010, and it was, again, the only private company to have delivered cargo to and from the International Space Station (ISS).

And if you’re wondering why there are such blatant mentions of SpaceX being a private company, it’s because the space industry had, all along, been the domain of governments and NASA.

So more than it just being proof of Musk’s success, the Falcon 1 and SpaceX represented something bigger – the rise of the private sector’s rapidly growing interest and progress in the space industry – what many might refer to as the ‘New Space’ movement.

For these New Space entrepreneurs, development of spacetech by governments and NASA have moved at a crawling pace over the years because costs of developing and launching are simply too high.

“We’re not even close to being on track to becoming a space-going civilisation,” said Musk in a USA Today article from 2005.

The main intention of New Space firms can be summarised as such – making space travel and exploration an attainable reality for more people by reducing the barriers of entry concerning access to space.

But this is not an article about Elon Musk.

And so, after all that preamble, we come to the main stars of this article – the Singapore team from Equatorial Space Industries (ESI), who, just like the billionaire, has strong ambitions of forwarding humanity’s progress in space exploration.

“Like Many Kids, I Dreamt Of Space For Years”

By day, Simon Gwozdz is a final year student at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

By night, he’s the CEO and founder of Equatorial Space Industries (ESI), a startup based at The Hangar at NUS Enterprise.

“Like many kids, I dreamt of space for years,” recalled Gwozdz.

“But it took me until a few years back when I started to learn the technology and science behind it – at which time, I got in touch with the local New Space scene and benefitted from the treasure trove of experiences from people working in it.”

It was also at that point that he started understanding the emerging niche for small launchers for nanosatellites.

Nanosatellites, while tiny (they can as small as 10 cubic centimeters), do pretty much the same things that regular-sized satellites do – but at a similarly tiny fraction of the usual cost.

Costing less than US$1 million to build and launch one into space, nanosatellites, in line with New Space, has enabled more individuals to collect data and pictures from space.

“Flocks of nanosatellites hold great promise, and many startups develop networks of hundreds of them for various functions at Low Earth Orbit,” shared Gwozdz.

“Nanosatellites benefit from being in a large number, very close to Earth. Therefore, constellations of these can provide continuous global coverage with very low latency. Some of the most common uses include earth imaging, observation, and remote sensing.”

But arguably the biggest opportunity is Internet of Things (IoT) communications – which is a key aspect of initiatives such as Singapore’s Smart Nation.

“Sadly, their only current option is to ‘piggyback’ them on a larger rocket, with a larger satellite, which doesn’t let them choose their target orbit at the right time.”

Larger satellite launches are also much more costly, creating an almost impenetrable barrier of entry.

But just like how access to computers were only for the rich and powerful decades ago, Gwozdz saw the potential for nanosatellites to also go ‘mainstream’, eventually benefitting smaller companies and individuals interested in space as well.

And the best way he could bring this vision to reality was to create a cost-efficient, high-frequency solution to nanosatellite launches – the goal that he and the ESI team have been working tirelessly to realise.

A Team Brought Together By A Passion For Rocketry

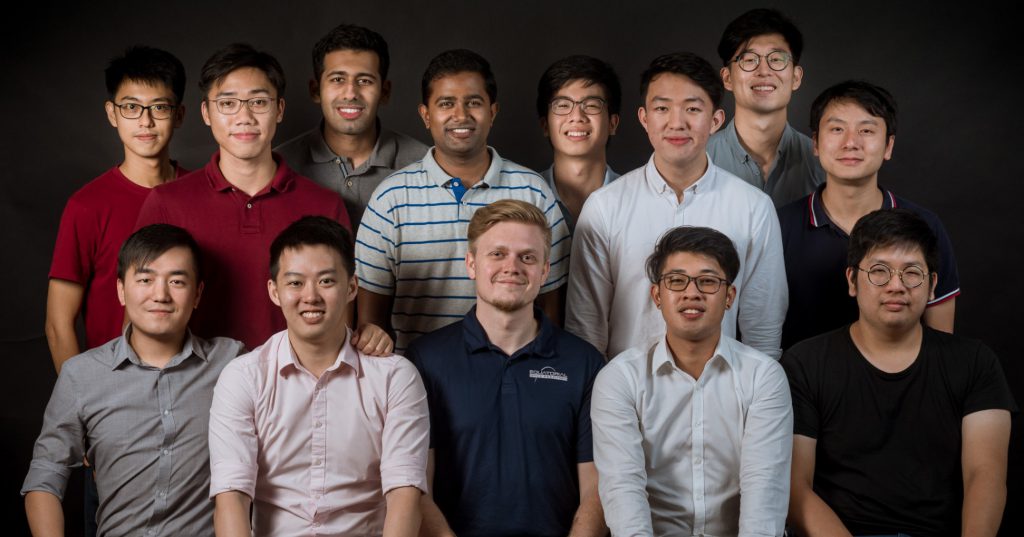

Mostly in their mid-twenties, the ESI team is made up of individuals from “many walks of life, [but] brought together by the passion for rocketry and the vision to be the first orbital launch company in the region”.

An NUS alumni himself, Eric Liu (one of ESI’s two software engineers) shared that there are also “several NUS graduates on the team”.

“They have full-time job commitments in various industries during office hours, but gather only in the evening to hack on the rocket engine.”

“Sometimes, we carry on working until 2am!”

Added Gwozdz, “It’s a challenge [to juggle full-time commitments and ESI work], but ultimately, we understand the massive opportunity and market necessity of small launchers.”

“If we are to capture this opportunity, we have to move as fast as we practically can – and that means working after hours despite the fatigue.”

Not surprisingly, the ESI team also draws a lot of inspiration from Elon Musk’s SpaceX, “which prove that private businesses can succeed and even outpace traditional players, which makes it an obvious inspiration to people like us”.

The New Space community “and the many brilliant people working to solve problems back on Earth using the nanosat platform, and who need a launch” have also been the batteries that keep the ESI team going despite the fatigue.

ESI’s ‘Volans’, And Its Monetisation Strategy

We now come to the main star of the piece – what the ESI team has been working on since its founding in 2017.

Called ‘Volans’, their rockets are optimised for 35-70 kg payloads depending on orbit, and are “the only one to offer such a payload bracket for orbits both polar and equatorial from day one”.

In terms of manufacturing the Volans, Gwozdz shared that they’re planning to have a production line “with a variety of fabrication machines working on each component”.

For proof-of-concept development so far, it’s actually surprising just how many of the required hardware can be bought off-the-shelf in this time and era!

“Naturally, quality sensors and actuators that we need tend to get pretty pricey, but are still accessible.”

With an aim to monetise on launch contracts, Gwozdz shared that there are “over 12,000 nanosatellites under development now”, and they’re confident that they can stand out from competitors with their ability to offer dedicated launches for smaller than average payloads.

“On top of this, the usual bread-and-butter details such as pricing, quality of service, and flexibility of schedule can make or break a company, and we work closely with prospective clients to deliver just what they want.”

Joked Gwozdz, “We may or may not sell hats and flamethrowers, too!”

Launching From The South China Sea, And Getting The Govt’s Attention

While their operations are fully based in Singapore, launching their Volans from even the most ulu part of the island is a no-no.

“Apart from lack of a safety buffer which would be pretty hard to come by, Singapore is surrounded by populated areas in Malaysia and Indonesia, and launching rockets over towns is a very bad idea!”

Instead, their Volans would be launched from a barge on the South China Sea, a location that “offers a beautiful range either northbound or eastbound” and more importantly, “won’t trouble anyone on land”.

Regarding legal matters, Gwozdz shared that their launches will require air traffic control clearance as well as licensing of the rocket for liability purposes as according to international law, and they are currently in touch with relevant agencies around the region in regard to this.

They’ve also been in touch with a few government bodies in Singapore.

One of them is the Economic Development Board (EDB), who they are in contact with for certain aspects of their project.

I’d like to say in 20 years, not having a space launch capability will be very much like not having an airport or a harbour, and Singapore’s strong industrial base and advantageous location could give us the ‘Changi of spaceflight’ for centuries to come.

One Of The Biggest Challenges So Far – Convincing People About New Space

Just like how friends and family “have been quite incredulous” when the team first unveiled their project, Gwozdz admitted that one of their most immediate challenges was convincing people from outside the industry “just how down-to-earth” New Space really is – no pun intended.

“Rockets, in essence, are an enabler of IT Infrastructure in the form of thousands of satellites currently under development.”

Also, it’s literally rocket science so it took us a while to get the hang of how to deal with the many, cross-disciplinary systems involved.

ESI is currently 100% bootstrapped, but the team has managed to operate with “remarkable cost effectiveness”.

“But as we work on new prototypes to prove our dollar’s worth, we are pursuing various grants and keep busy getting in touch with prospective investors in preparation for our Seed Round,” revealed Gwozdz.

With manpower on a voluntary basis (i.e. team members are not paid), Liu added that, “The people who are already in the team fully understand that we all must work very hard until we get funded, so rocketing can become a real career in this country.”

Is Sending People To Space In The Works?

Ending off the interview, I had to address the elephant in the room – are there any intentions to eventually send people to space?

“Manned flights are a whole different beast – in terms of launch mass, required reliability and the complexity of life support systems,” said Gwozdz.

“But give me a call in a few years, and we will see what can be arranged!”

I’d like to thank Gwozdz and his team for their time, and explaining to me the intricacies of space tech!

Currently, the team is preparing for a full-thrust test of their scaled-down prototype before developing their first round of flight hardware. Follow their progress on their website here.

Also Read: For Gamers, By Gamers – How Razer CEO Min-Liang Tan Built A Cult Brand From A Gaming Mouse