The electric vehicles (EV) market in Singapore is currently gaining massive traction, fuelled by the clear commitment of the government and major players to electrify mobility and install charging points across the nation.

Clear goals have been set by the government, with up to 60,000 charging stations to be deployed by 2030 and plans to phase out internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles by 2040.

Back in 2018, Singapore had introduced the vehicular emissions scheme for cars and taxis, which allows car buyers and taxi operators who choose cleaner car models to receive an upfront rebate of up to $20,000 and $30,000 respectively.

In the recent Budget 2021 announcement, Minister Heng Swee Keat announced that Singapore will be setting aside S$30 million over the next five years for EV-related projects and initiatives, such as measures to improve charging provision on private premises.

Starting in 2021, those who purchase electric cars and taxis will receive a rebate up to 45 per cent on the additional registration fee (ARF), capped at S$20,000. Road tax for electric vehicles will also be lowered.

While the EV and green energy proponents are celebrating these ambitious goals as well as revisions in tax schemes and budget allocation, we have to carefully assess whether the government has really taken all the practical steps needed to make good of their public declaration.

Despite launching incentives to push for EV adoption, it seems that the current government’s policies have not addressed a major blindspot: what do we have to do to phase out the fuel vehicle and oil industry?

Disincentivising The Petrol Economy

Norway, the world’s largest per capita market in electric vehicles, becomes a paragon of example.

According to the Norwegian Road Federation, full electric cars made up 54 per cent of all new cars sold in Norway in 2020, marking the first time they outsold ICE vehicles for a year as a whole.

With over 8,500 charging points, its EV sales accelerated in end-2020, reaching a peak in December with a 67 per cent share of the car market.

Norway owes its success to both the carrot and the stick approach. It offered extremely generous incentives to EV buyers, and financially punished people who continued to use gas or diesel cars.

While Singapore has begun to introduce the ‘carrot’ in terms of tax breaks and funding to push for EV-related initiatives, Singapore has yet to introduce a stringent ‘stick’ approach to disincentivise people from continuing to use fuel cars.

Minister Heng did not elaborate in detail on measures to reduce the number of existing petrol vehicles on Singapore roads within the 20-year timeframe.

Separately, he announced that the increase of petrol duty rate — $0.79 for premium fuel, and $0.66 for intermediate grade fuel.

However, this duty hike is likely to cause only a marginal impact on the cost of living of petrol car users in the immediate term.

Furthermore, the duty hike will only have a limited impact on the petrol industry at large as petrol companies will likely pass on the price increase entirely to consumers.

Moreover, only 20 per cent of our local refinery production of petrol and diesel is reserved for domestic use. Growing regional demand for these fuels elsewhere will most likely replace the displaced domestic demand.

Currently, Singapore is still dubbed the “oil hub in Asia” and the oil industry accounts to as much as 5.4 per cent of the country’s 2020 GDP.

So how prepared is Singapore to shift the revenue from oil and gas, to green energy?

Have there been concrete plans in place to phase out fossil fuel projects and contracts, and subsequently, concrete schemes to absorb displaced manpower and retrain them to integrate into the green energy revolution?

Instead of relying on clearer direction from the government, currently the onus seems to lie on private fossil fuel providers to find ways to fundamentally support the city-state transformation into a clean energy hub.

For example, energy giants such as Royal Dutch Shell have started rolling out EV charging points at gas stations in Singapore since 2019.

Shell has announced major investment in renewables, planned to cut its crude processing facilities in Singapore by half, and expanded its portfolio of lower-energy carbon solutions.

Owning A Petrol Vehicle Is Still Cheaper Than An EV

Singapore has a much higher initial purchase price for vehicles compared to other countries in Southeast Asia. Despite the multiple subsidies given by the government for EVs, it is still difficult to establish a levelled price.

An EV costs between S$100,000 and S$160,000 for mass market models, and might not be the most affordable option out there on the market.

There are also currently limited Battery-Powered Electric Vehicle (BEV) models available in Singapore — mostly high-priced brands, and a few alternatives for fleet applications like taxis, last-mile delivery, service and utility cars.

According to a Rakuten Insight Survey in 2019, the awareness of available electric car brands in Singapore is still very low, way less than 50 per cent on average per brand.

The recent Budget 2021 announcement also did not address the topic of the annual additional flat road tax component.

Since EV drivers do not need to pay petrol taxes, an additional annual lump sum tax of S$200 in 2021, S$400 in 2022 and S$700 in 2023 is imposed, significantly increasing vehicle-related taxes.

Given the available land transportation choices available for the average Singaporean household, the most affordable option is still the cheaper models of petrol vehicles, or the public transport route.

Walter Theseira, associate professor and head of the Urban Transportation Programme at the Singapore University of Social Sciences, said the key issue was whether the auto industry would be ready.

If it’s not ready and there aren’t enough zero or low-emissions vehicles on the market, no policy tool will work because the public will perceive a huge loss in choice and availability of cars.

– Walter Theseira, associate professor and head of the Urban Transportation Programme at SUSS

Thankfully, current trends in the global auto industry seem to be going in alignment with the government’s 2040 goals.

Big markets such as China, Japan, United States and India have been racing to produce more variety of EVs.

Luxury car makers such as BMW and Rolls Royce that traditionally produced higher-end and fuel-heavy cars have also jumped onboard to develop luxury electric and renewable models.

To further accelerate this transformation, perhaps the Singapore government should look into more stringent ways to ‘punish’ the continuous production, sales, and purchase of ICE vehicles.

Other Blindspots In S’pore’s EV Infrastructure Plans

According to Andrey Berdichevskiy, Singapore-based leader of Deloitte’s Global Future of Mobility Solution Centre, charging installation is highly dependent on the land and car park ownership — a landscape that is highly fragmented in Singapore.

An orchestrated approach involving major owners and operators of car parks (e.g. HDB and major real estate players), other points of interest like gas stations, as well as fleet-related infrastructure is urgently needed to accelerate EV charging adoption in Singapore.

It is not enough that the government declares an intention to “install more charging stations”.

There needs to be a more integrated approach among government agencies – comparable to the efforts in autonomous vehicles spearheaded by the Land Transport Authority (LTA) – to bring relevant players together in a coordinated manner to roll out the public, private and destination charging in Singapore.

– Andrey Berdichevskiy, leader of Deloitte’s Global Future of Mobility Solution Centre

In an email statement to Vulcan Post, he explained that there are three other big areas the government has not addressed to ensure a smooth transition to full electrification:

1. Repair expertise

Supporting end-users in overcoming EVs ownership complication is key to encouraging greater adoption.

Even in markets with more advanced EV systems, repair expertise remains an important issue, as many ground technicians lack sufficient knowledge of EV systems.

Efforts that OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) are investing in this area include the replacement of workshops with body shops in markets such as Norway, where bodyshop technicians — unlike repair technicians — are required to undergo advanced training programs to perform work involving high voltage battery systems.

2. Affordable insurance scheme

As EVs are a relatively new vehicle type and more costly than conventional ICE vehicles, users are likely to be more concerned about their safety aspects and other cost-related issues that may arise.

Insurance coverage may therefore be a key consideration in the purchase decision. Currently, many insurance players have already begun integrating EVs into their quotation systems, although the premium rates for EVs are still relatively higher than conventional ICEVs due to the higher associated repair costs.

3. Market for second-life batteries

The recycling of used electric batteries is a significant feature of the sustainability benefits of EV adoption.

For example, about 75 per cent of EV batteries can be remanufactured into other vehicles or stationary energy systems. To tap into this immense potential and capitalise on the scarcity of lithium and other rare-earth elements, Southeast Asia (SEA) will need to develop its second-life market by building necessary technical capabilities.

In short, the government needs to think like an average consumer who is taking his or her first step switching to EV and make it easy for everyone to do so.

Before introducing the stick, it is also important to prime a very attractive and attainable carrot.

The government needs to incentivise usage, not solely the purchase — usage incentives can help to minimise TCO (Total Cost of Ownership), improve the convenience for private usage, and effectiveness for commercial deployments.

Lacking Public Reinforcement, Campaign, Education

Lastly, a more concerted public and private collaboration and campaigns across all boards need to happen in order to realise the government’s agenda by 2040.

For instance, the government needs to leverage the electric vehicle economies at scale via fleet electrification.

According to Deloitte, fleet use cases such as ride hailing, logistics, and public transport in SEA have an annual kilometres travelled of about 450 per cent more compared to private-use vehicles across countries.

With smart charging schedule optimisation, the downtime of electric fleets can be significantly reduced, and utilisation of charging stations can be increased with positive impacts on the return on investment of an electrification strategy.

The government has already started to invest massively in such schemes.

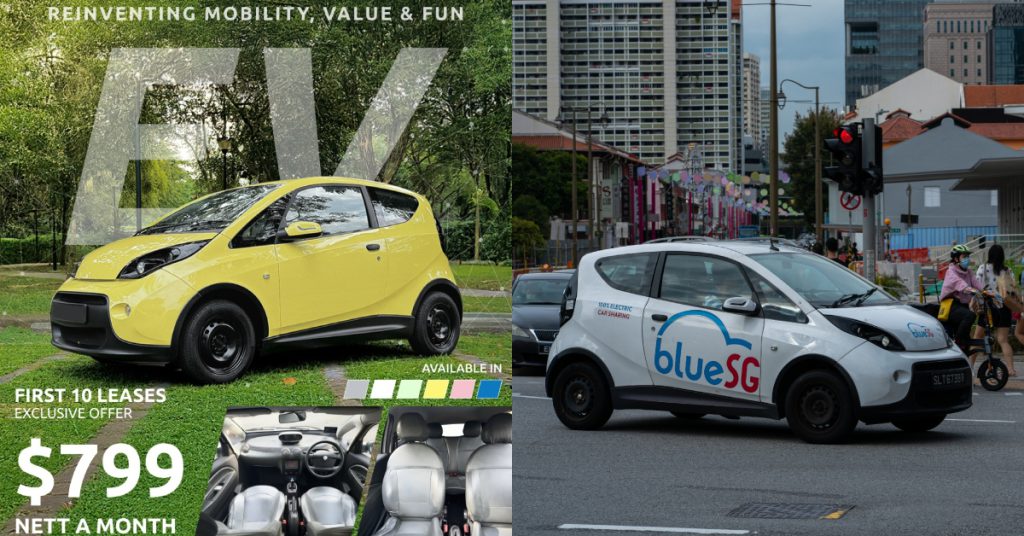

BlueSG is the world’s second largest electric car sharing services and it has since been growing rapidly. However, there are currently only 667 BlueSG cars available in Singapore.

Other projects such as electric shared scooters, electric taxis, and electric buses are still in trial development phase.

Public campaigns and education need to be implemented at all levels of the society to change generational mindset and shift perception.

A recent Deloitte Future of Mobility survey revealed that concerns about climate change ranks lowest among the reason Singaporeans choose to acquire an EV.

Lower fuel cost, ease of maintenance, better driving experience and government incentives seem to be their top reasons in making the shift instead.

This is however, not ideal. Societal behaviour hinges too heavily upon governmental ‘carrot and stick’ schemes, and may be easily swayed with any changes in the policy or economic development.

For an absolute and permanent transformation to take place, more Singaporeans — especially the younger generations — have to become more aware and conscious in limiting their carbon footprint for posterity.

A sort of moral imperative needs to permeate the national consciousness to compel new car owners to jump onboard the EV train.

Not just economically, culturally and socially, the government has to introduce measures to change our society’s belief system. For example, it can introduce compulsory green lifestyle programming and syllabus into Singapore schools’ curriculum and public service announcements.

A nationwide fully electric mobility is definitely not an impossible goal. The question does not lie in whether we will make it happen, but rather when and how we are going to get there.

Featured Image Credit: SP Group