Much has been said about Singapore’s resilience to the economic woes caused by the Covid-19 pandemic — in no small part thanks to its deep reserves that provided the necessary resources to keep the economy afloat, without forcing the government to go into debt to bail out local citizens.

But there’s another characteristic of Singapore economy that has gone largely unappreciated and ironically, is also often a target of scorn from some Singaporeans and local wannabe politicians: its labour market.

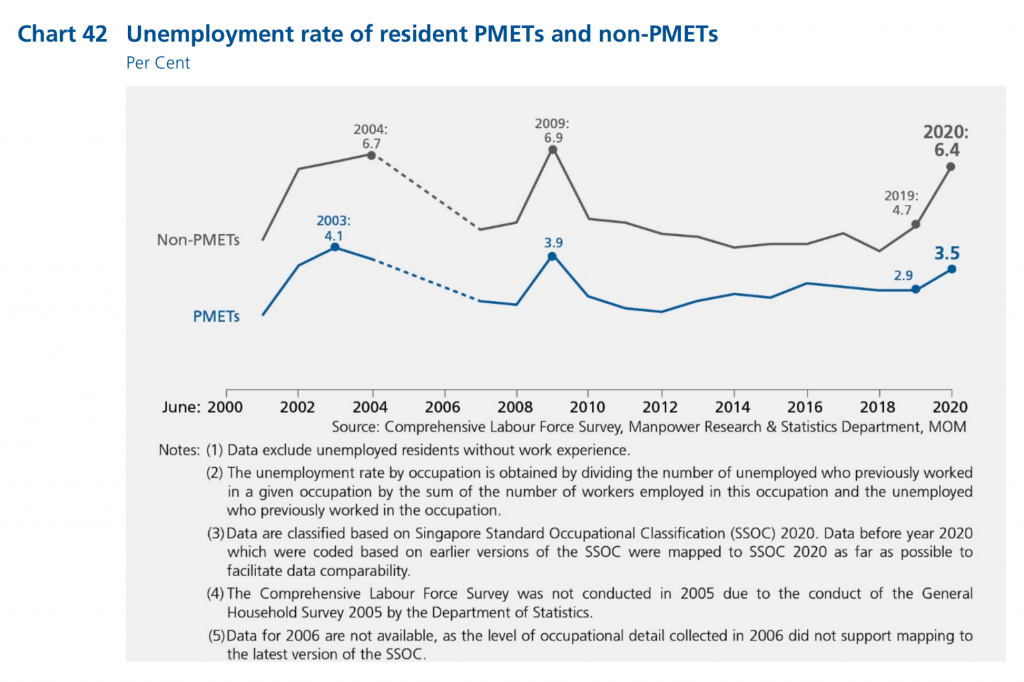

With unemployment rate at 3 per cent overall and 4.1 per cent for residents, the country is the envy of the world, where the rates are at least two to three times higher right now.

Despite the severity of the crises, it is also lower than what the country experienced a decade ago, in the aftermath of the financial meltdown in the United States.

Learn From ‘Handicapped’ Countries

Rory Sutherland, vice-chairman at Ogilvy and a man who dedicated his life to studying human behaviour (turning it into a goldmine for the renowned advertising agency), once remarked that to seek innovative ideas you have to look at the extremes.

An example he gave in an interview referred to improvements in modern mobile devices and apps, and how it could pay to look at them as if you only had one hand.

How useful and accessible are they then? How can they be made simpler, smaller, thinner et cetera to be made easier to use if you couldn’t use two hands?

Examining such outlying scenarios can yield improvements for all users. This works as a good analogy for entire countries as well.

You will find many great ideas among those who have less or who are constrained by unfavourable circumstances — as if they were, for one reason or another, handicapped.

Take Japan, for example. It’s a country ravaged by earthquakes, which has few natural resources and yet is one of the most developed and innovative in the world.

The same logic applies to Korea, Taiwan or even Singapore, while resource-rich nations like Russia, Gulf Arab states and neighbouring Malaysia are trailing behind. Their greater natural wealth has not transformed into greater creativity. It’s quite the opposite actually; it has made them complacent.

The world was after all, once colonised by relatively small European nations, which were in competition with each other over resources and trade with distant — and far more populous — lands in Asia.

Great Britain, the windswept collection of rocks in the Atlantic, was not so long ago an intercontinental empire that the sun never set over. A nation of 10 million people (ca. 1800) conquered India, humiliated 300+ million-strong China and was the source of the industrial revolution that transformed the planet.

Therefore, it pays to look at small nations — that are constrained by geographic circumstances yet are still doing well against all odds — for inspiration and what their successes tell us about future trends.

Singapore is such a country in many ways, but its immigration policies and resilience of the labour market rarely come into focus.

Where Singapore Stands In The East-West Divergence

When you examine the labour markets, the developed world is now broadly divided into two groups of countries: those which try to embrace immigration and fail at it (struggling to deal with various sociopolitical and economic consequences of importing millions of migrants), and those which refuse or find it hard to open up, although they may soon be forced to by the circumstances.

The first group is of course, Europe and North America, which see an influx of immigration that is much needed for their ageing societies. Yet, it proves to be highly problematic to manage, leading to instability, crime, political polarisation and poverty.

This is in opposition to East Asian countries, like China or Japan, which are also ageing at a rapid pace. However, due to their insular cultures, strong ethnonational identities and difficult languages, they are not open to foreign immigration — which can lead to severe economic consequences in the future.

They will simply lack qualified labour, with ever-increasing number of pensioners who are only going to consume, but not produce anymore.

Singapore is a notable outlier, straddling this great divide. It’s a developed, mainly English-speaking country based in Asia, with a large local Chinese majority (around three-quarter of local citizens).

With the lowest fertility rate in the world, it is ageing rapidly; yet it is open and welcoming to immigration into all social strata and from all destinations, as long as they have the required skills and a job offer.

Its measured approach created a mosaic of ethnicities, cultures and religions — easily the most multi-cultural country in the world — which is also the world’s safest and most prosperous. It has already achieved what no one else has.

Prioritising Job Security For Singaporeans

Before the pandemic, out of 5.7 million people in the country, only 3.5 million were citizens.

The remaining nearly 40 per cent consisted of various groups of migrants — permanent residents, qualified employment pass and S-pass holders, as well as lower tiers of work pass holders, including maids and construction workers.

Singapore has limited space, so it could never afford the generosity of wide open borders witnessed in Europe or America. Like in the example I brought up above, it has to operate with just one hand and make the most of it.

It cannot simply allow all incoming workers to bring their families with them. Only upper-tier immigrants with considerable qualifications who are likely to be in short supply locally can both command the necessary salaries and be seen as valuable enough to be allowed to relocate with families.

This carefully-designed system allows for remarkable flexibility that provides resilience to the local labour market and is the best compromise for all participants, while protecting the core resident workforce.

It has allowed the diminutive city-state to attract much-needed world-class talent, as well as hundreds of thousands of relatively cheap workers performing menial tasks that the local inhabitants no longer want to do.

It has helped to grow the quality of local labour force, ensuring that the smartest people can call Singapore home, regardless of where they were born.

Meanwhile, physical workers can make good money here, while supporting families in considerably less costly locations in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Philippines, Indonesia and so on.

In case of a crisis making them redundant, it creates fewer problems locally (unemployment and resulting poverty), while allowing them to retreat to a much cheaper life back home until the situation goes back to normal and they can return. It’s a win for everyone, which allows for flexible and fair working conditions for all.

As a result, quite remarkably, the overall employment for Singaporean residents increased by 15,000 by the end of 2020, with foreign workers bearing the brunt of the pandemic-induced cuts. Over 180,000 lost employment during the year, mainly in low-end jobs in construction and manufacturing, which were most impacted due to the crisis.

You may think that this is me being at my cruelest and most heartless. After all, they are people too, with lives, families and careers.

But the truth is that the situation would have been much worse if they lost their jobs and had to support themselves and their families in Singapore instead of taking a temporary refuge back in their home countries. It is typically much more affordable to live in, where they can rely on a much larger circle of friends and relatives.

It would be bad for Singapore as the country would have to support them somehow. It would be bad for them too, as they would be struggling to find employment to bear the much higher living costs. Poverty and crime would likely follow, as they typically do elsewhere.

Due to the regulated nature of Singaporean immigration — which does not permit settling down in the city unless you can really afford it and your skills guarantee a sufficient income (and benefit for the country) — it spares people much more painful experiences during economic busts.

At the same time, it never closes the doors for their return. They can do so when the situation improves and more workers are needed.

It’s a strictly needs- and merit-based system that prevents emergence of pockets of poverty and social exclusion during downturns, while prioritising job security for local residents.

A Glimpse Into What The Future Holds

Singapore’s labour market is years ahead of all other countries, foreshadowing the future of employment in the developed world.

As entire nations grow both wealthier and older, they will have to grapple with gaps in workforce on all levels in the economy. To fill them, they’re going to compete for talents who are able and willing to do these jobs — from sweeping streets to nuclear physics.

At the same time, they will be forced to manage social ills that often come with mass immigration, which may fuel nationalistic sentiments and pit the societies against the newcomers, especially if their influx is not carefully managed.

To avoid these issues, immigration has to be tied to available employment and privileges associated, with it restricted depending on a person’s ability to fend for themselves and their dependents — like how it’s like in Singapore.

When managed properly, a large migrant workforce won’t be a problem, but it also elevates the local economy and protects the jobs of local residents. Their lives are surrounded by a protective buffer of flexible migrant employment, which can be adjusted quickly in times of crisis.

Featured Image Credit: Shadow of light / Shutterstock