Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

Last week, for the first time ever, Singapore’s Supreme Court issued an injunction blocking the sale of a Non-Fungible Token (NFT).

The NFT in question was from the famed Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC) series, a collection of NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain that has totalled more than US$16 billion in sales. NFTs from this collection have been purchased by celebrities including singer Justin Bieber and DJ Steve Aoki.

The disputed NFT was BAYC #2162. It was owned by Singaporean Janesh Rajkumar, though it is now in the possession of the defendant only known as ‘chefpierre’.

Facts of the case

The dispute is primarily over ownership of BAYC #2162, which in addition to being a rare item, is one of Rajkumar’s most prized assets. He had “no intention to ever part with or sell” it.

He had initially entered into a loan agreement with chefpierre on NFTfi, a decentralised borrowing and lending platform. The agreement stipulated that Rajkumar would pledge BAYC #2162 as collateral in exchange for a loan from chefpierre.

Rajkumar is a frequent borrower on NFTfi, and chefpierre is a frequent lender on the platform. The agreement also stipulated that chefpierre would not be able to foreclose on the loan if Rajkumar was unable to repay the loan on time. Instead, an extension on the repayment would be granted.

However, when Rajkumar failed to repay the loan by this second deadline, chefpierre foreclosed the loan and moved BAYC #2162 to his personal wallet, where it ended up for sale on OpenSea.

Rajkumar then claimed that this was an act of unjust enrichment — the loan agreement forbade foreclosure of the loan, so Rajkumar is suing to get his NFT back.

The court injunction ruled that NFTs qualify as a digital asset that could be protected, and prevents any sale of BAYC #2162. OpenSea complied with the injunction, marking the NFT as “reported for suspicious activity” on their site.

Lead counsel for Rajkumar, Shaun Leong from Withersworldwide, celebrated the win.

He told Bloomberg that the decision is the first in a commercial dispute where NFTs are recognised as valuable property worth protecting, and that the injunction and ruling implies legal recognition that NFTs are a digital asset and people who invest in it have rights that can be protected.

Legal protections: can of worms?

While many are celebrating the legal interference of Singapore’s legal system in protecting the rights of NFT holders to private property, a question that needs to be asked is what happens when we take this trajectory to its logical conclusion.

NFT holders might now be happy that their NFTs are now classed as assets, and entitles them to some legal protection. But what happens if there are multiple competing jurisdictions, with multiple different precedents on what should happen?

A hypothetical scenario could be this: When an NFT becomes disputed between two claimants, both with plausible claim to be the rightful owner, they may not necessarily belong in the same legal jurisdiction.

If both obtain injunctions or even rulings that the NFT rightfully belongs to them, who becomes the final arbiter?

This no longer becomes a case of disputed property — it is now a case of competing competencies between two legal systems, with no basis of enforcement, or method of resolution. Even if this situation does not arise, legal proceedings are fair only when both sides are able to tell their side of the story.

One of the key features of the cryptocurrency and NFT worlds is the offer of anonymity for users. In this case, Rajkumar surrendered his anonymity to bring the case before the court, while chefpierre chose not to surrender his anonymity and present his claim.

Before this, the world of NFTs has no legal system to resolve disputes, partially because the Ethereum blockchain’s smart contracts have worked so far to ensure that contracts in bad faith are difficult to make. Smart contracts are automatically executed and activities are tracked on the blockchain, making it difficult to hide and obscure user actions.

However, concerns can arise when we deal with unintentional conflicts — when contracts are poorly worded, or the letter of the law is obeyed without regard to its spirit.

Is relying purely on court orders from a multitude of different jurisdictions then a good way forward for the NFT community? Probably not.

Of the community, by the community, for the community

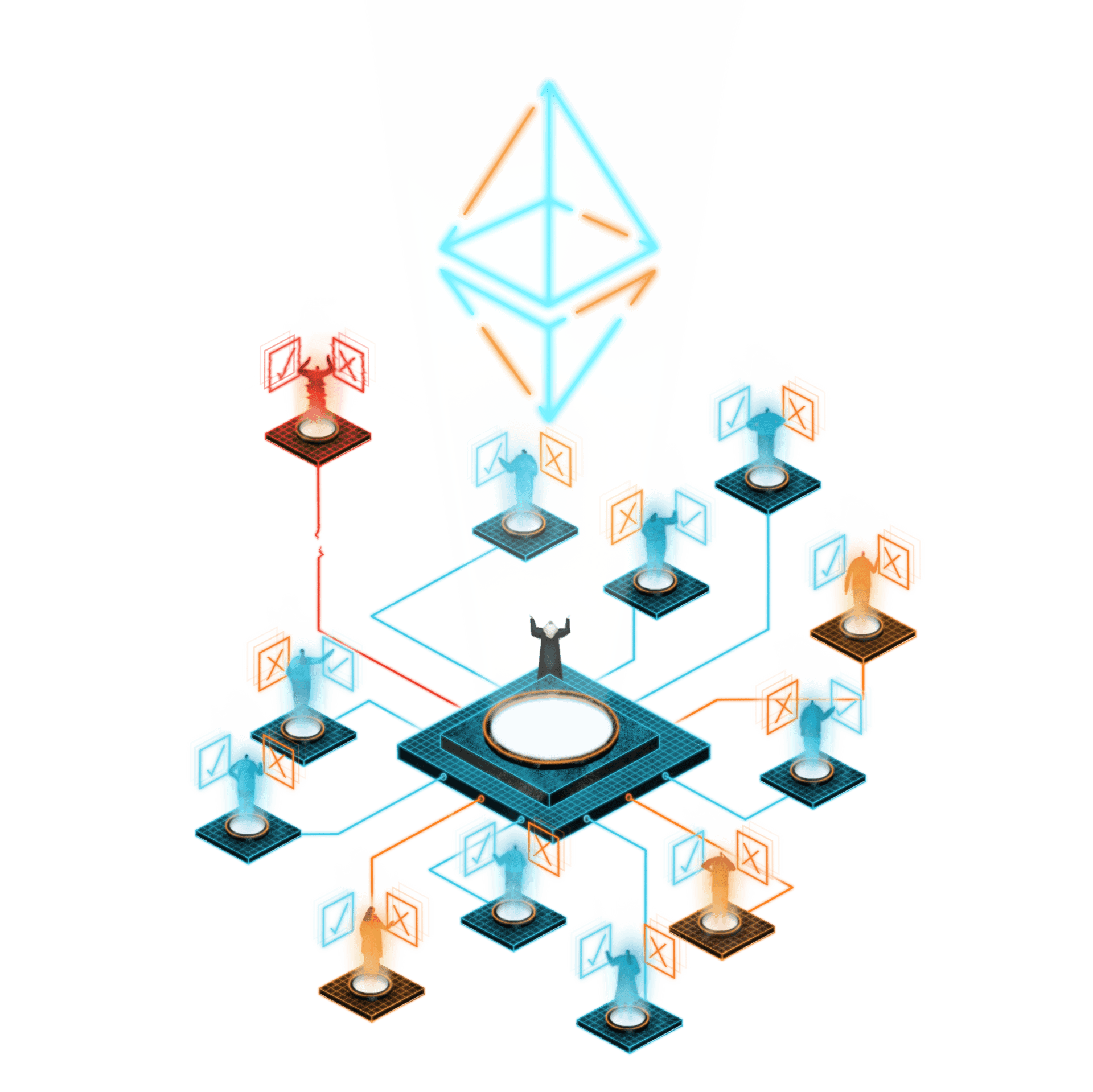

The NFT space already has some degree of decision-making capability and the mechanism to back it up: the decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO).

DAOs rely on proofs of ownership of governance tokens, transparent votes, and act as a form of governance platform for blockchains.

A solution for legal disputes within the NFT community should, ideally, be wholly contained within the NFT community. A DAO can provide this — with legal experts being trained to provide legal and binding judgements to which NFT platforms such as OpenSea can answer to.

However, that does not mean precluding and ignoring judgements made by sovereign courts. On the contrary, it might mean working with these courts instead.

As NFTs rise in popularity, these disputes might become more commonplace. Platforms like OpenSea might have to contend with conflicting orders from multiple jurisdictions.

A DAO-style court of NFT holders might resolve this by considering the merits of every case, and providing a definitive source of authority for which NFT platforms might obey.

Since these organisations are comprised of NFT holders and other members of the NFT community, they would be better suited to determine if any party has acted out of line, or to arbitrate disputes between rival claimants.

Additionally, a dispute resolution mechanism within the NFT community may provide an additional guarantee for sceptics who are not yet confident in the security of their investment, and offer them some chance of legal recourse where there was previously none.

While the interjection of Singapore’s supreme court has now provided some guarantee, this guarantee is limited — it exists in Singapore and may not be recognised elsewhere.

A DAO to resolve such legal disputes — that is part of the decentralised community that fully understands the culture, expectations, and importance of what is at stake — would be much better equipped to deal with these disputes on a regular basis than courts that often lack the expertise on a complex subject matter that is the NFT world.

As the NFT landscape gets more complex, disputes are going to become increasingly difficult to avoid.

This dispute over BAYC #2162 may seem isolated now, but there are already other similar cases. Just last month, UK’s High Court ruled that NFTs are considered property, allowing them to be frozen through court injunctions.

The uncertainty of protections being offered evenly everywhere in the world offers a strong reason for why the NFT community itself might benefit from its own dispute resolution mechanism — a DAO, court, or anything else, that might guarantee fair protection and participation for anyone involved — wherever they are on the planet and whoever they might be.

Featured Image Credit: MetaGaming