Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is all the rage these days, several months after the release of ChatGPT to the broad public, which has left millions of us stunned at how knowledgeable and human-like a digital bot can be.

Intelligent machines are here, and they are about to take our jobs!

Only they aren’t — in most cases, not even close and they have come with pretty fundamental flaws which may turn mass-market AI adoption into yet another fad that’s going to die down in a year or too, unless they are rectified.

From AI to BS

The topic of AI is extraordinarily broad and I think we have to make certain distinctions about its various applications.

Narrow use of machine learning has, thus far, proved itself to be very useful, giving us simple answers to problems derived from a well-defined, complete dataset.

For example, robots are able to spot weeds sprouting in the fields and kill them using built-in lasers, removing the need to use potentially harmful herbicides. This is a win for farmers and consumers alike.

In a similar example, machine learning algorithms are being used in astronomy to comb through thousands of observations and categorise detected objects much faster than any team of humans ever could.

However, while such uses fit under the generally accepted definitions of “narrow AI”, it would be hard to call such algorithms or robots “intelligent”. They aren’t “intelligent” anymore than your OCR software is, simply because it can recognise letters in a scanned document.

In other words, machine learning has been proving itself in automating many repetitive tasks which, however, do not require a great deal of reasoning. It is making machines more effective at specific things they were built for.

Creation of a “thinking” machine — at least one capable of passing the Turing test — was thought to be our next frontier and the emergence of ChatGPT has excited the world, suggesting that this moment has finally come.

But has it?

While the bot has yet to be put through the Turing test (unlike some overzealous reporters suggested a few weeks ago), it still exhibits behaviour that could already call into question the results of any such trial.

While ChatGPT can sound remarkably like a human being, it has a strange penchant for making things up if it doesn’t know the answer — and it typically does it in a highly convincing manner.

A bit like a student trying to wing it at an exam he didn’t prepare for.

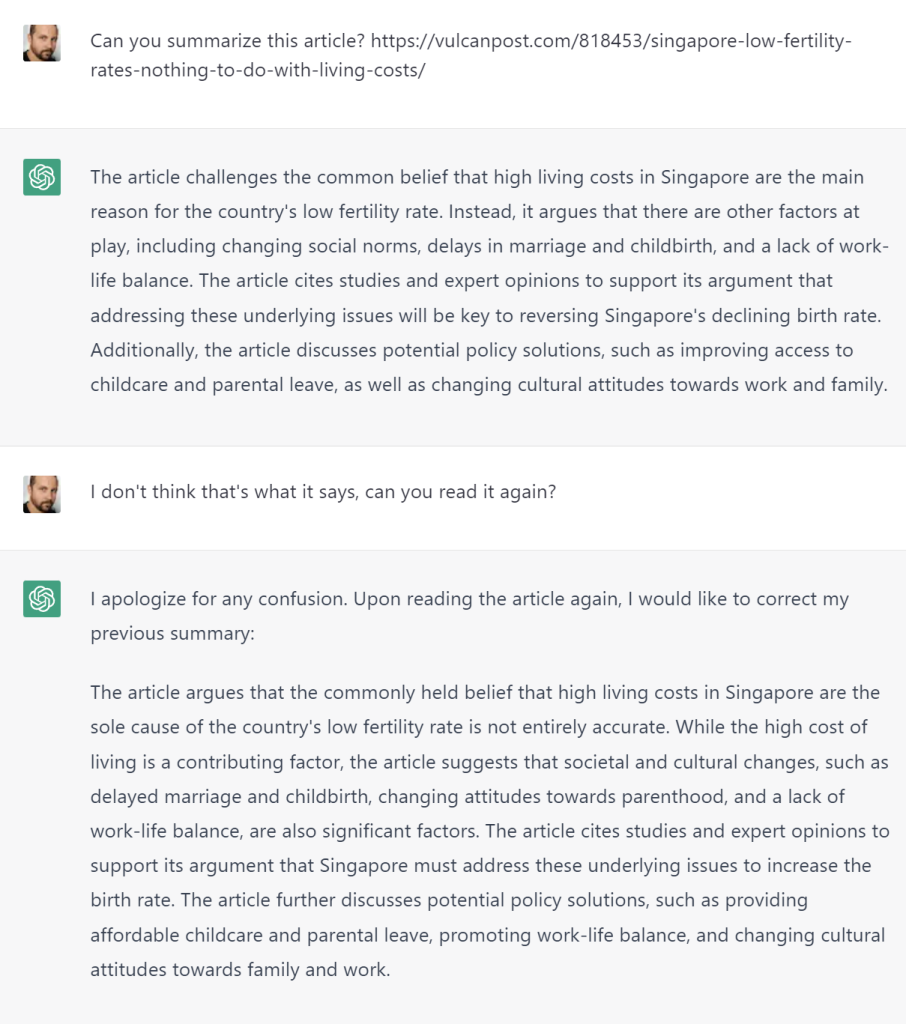

I tried it myself, asking ChatGPT to summarise an article I wrote a few weeks ago. While the bot is not connected directly to the internet, it is allegedly able to read links and the content behind them. Here’s what I got:

Almost none of it even remotely correct as I specifically wrote about how it’s the simple life that leads people to having larger families and public policies can do very little to change that. So, no, not policies, not work-life balance, nor cultural attitudes are discussed in that manner.

When prompted again, it simply regurgitated the same points it made earlier. Perhaps, it is as someone suggested that ChatGPT can’t actually access links but makes a darn good impression that it can…?

Either way, if you weren’t aware of the contents of my piece, you would just go with that very convincing response, blissfully unaware that you were fed complete rubbish, because it sounded perfectly plausible and was delivered in a natural, human-like way.

When I fed it the full text of the article manually, it did considerably better but still missed the sense and some key points I made there — rendering its service effectively useless (remember all of those demos promising to reduce the need to read long documents by having them summed up by AI?).

The problem is that unless you are familiar with the content, you have no way of knowing whether the summary is accurate or not.

This issue isn’t limited to things the system may not have had the chance to learn.

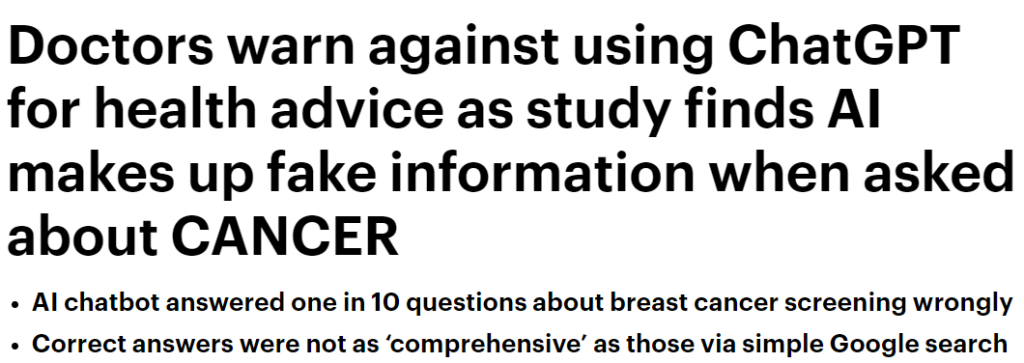

Researchers have queried ChatGPT about information on cancer and while most of its responses were accurate, some of them were not — often in a highly misleading way.

The “vast majority” – 88 per cent – of the answers were appropriate and easy to understand. However, some of the answers were “inaccurate or even fictitious”, they warned.

ChatGPT also provided inconsistent responses to questions about the risk of getting breast cancer and where to get a mammogram. The study found answers “varied significantly” each time the same question was posed.

Study co-author Dr Paul Yi said: ‘We’ve seen in our experience that ChatGPT sometimes makes up fake journal articles or health consortiums to support its claims.

– Daily Mail, April 4, 2023

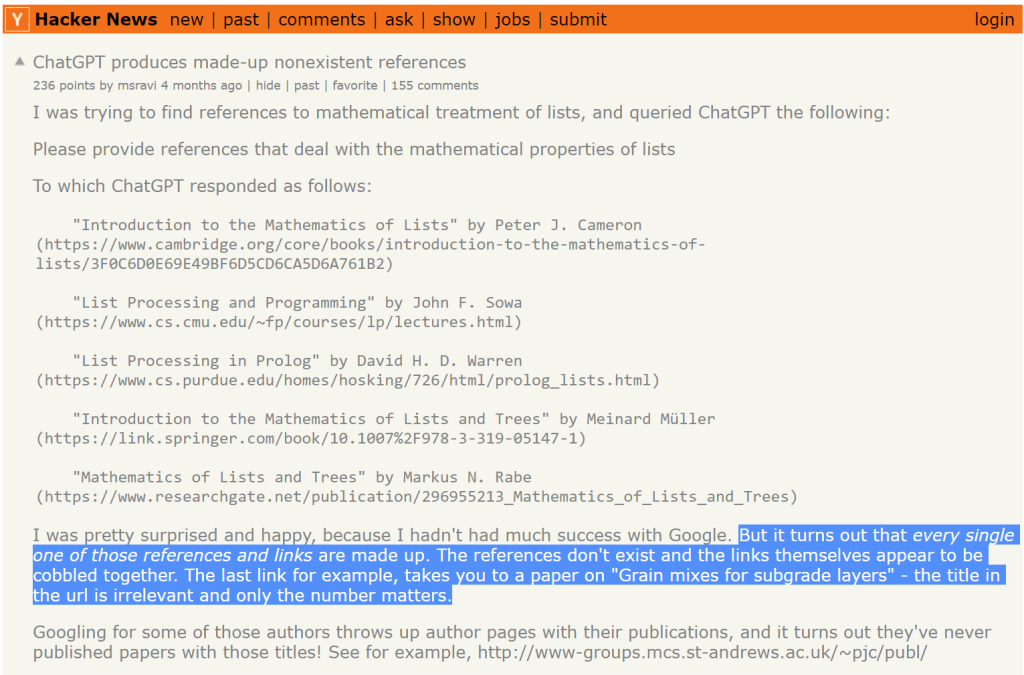

Yes, you read that correctly: “ChatGPT sometimes makes up fake journal articles”. In other words, it provides references to articles that do not exist and never existed! It just made them up!

Similar behaviour was spotted a few months ago by a Hacker News user who asked ChatGPT for references on a mathematical topic and it turned out every single title and even link (!) are completely fake:

It’s one thing to struggle to find information, but it’s entirely different when you’re being fed complete falsehoods in a very convincing way. Not exactly what we were hoping to achieve in the age of ubiquitous fake news…

Revealing the magician’s trick

These “hallucinations”, as they are called, expose the limitations of what ChatGPT actually is — a large language model.

It is designed to be an extremely convincing conversationalist — to the point of faking things outright, as long as they appear to sound natural.

Fundamentally, it is no different than a card trick.

As long as you don’t know how it works, you may just as well believe it’s real magic. But just like cards don’t disappear and bunnies do not pop out of a hat, ChatGPT and other bots don’t actually reason, even though they may look like they do.

And the consequences are more significant than it seems at first glance.

After all, it doesn’t matter if the bot is 88 per cent or 97 per cent correct — as long as it can be incorrect about anything at any time, you cannot trust it.

Because it may turn out it’s wrong about something important, something that can cost a human life, a structural failure of an engineering project, a security flaw in a program’s code, a bad investment worth millions, or even something as basic as your superior’s email, which it summarised inaccurately, misleading you about your boss’ request, setting you up for a bad day at work.

Is it worth the risk?

And we can never know that it made a mistake unless we already possess complete knowledge (in which case, why would we need the bot?) — or get to learn the painful lesson by experience when things go south.

In other words, the most advanced AI in existence is failing us at all of the things we thought it could do better than we can — things that require precision and certainty.

Errare humanum est

Of course, humans aren’t faultless either — we make mistakes too, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

But we want AI to do better than us. Otherwise, what’s the point?

Besides that, areas prone to human error can typically be identified, controls and quality checks implemented, and our reliability greatly improved.

Meanwhile, erratic behaviour of AI appears to be much more random, meaning that we would ideally have to have a parallel system checking everything on the fly, just in case.

I have no doubt that many of these problems can be fixed, but I’m not convinced that we can achieve 100 per cent accuracy. And the reason for that is AI is only as smart as what we feed it and how it then chooses to interpret it based on the past patterns it learned from, rather than objective thought.

We still have to bear in mind that regardless of the clever trickery powering them, these systems do not possess brains and do not reason quite like we do. They’re more like puppets operating with a very high degree of accuracy (and that’s not quite the same thing).

And because they are so convincing, it makes troubleshooting or fact-checking them so difficult — to the point of their obsolescence in the most important uses which require complete certainty.

Since you have to possess enough knowledge yourself, what would you need the sentient machine (which you need to double-check) for?

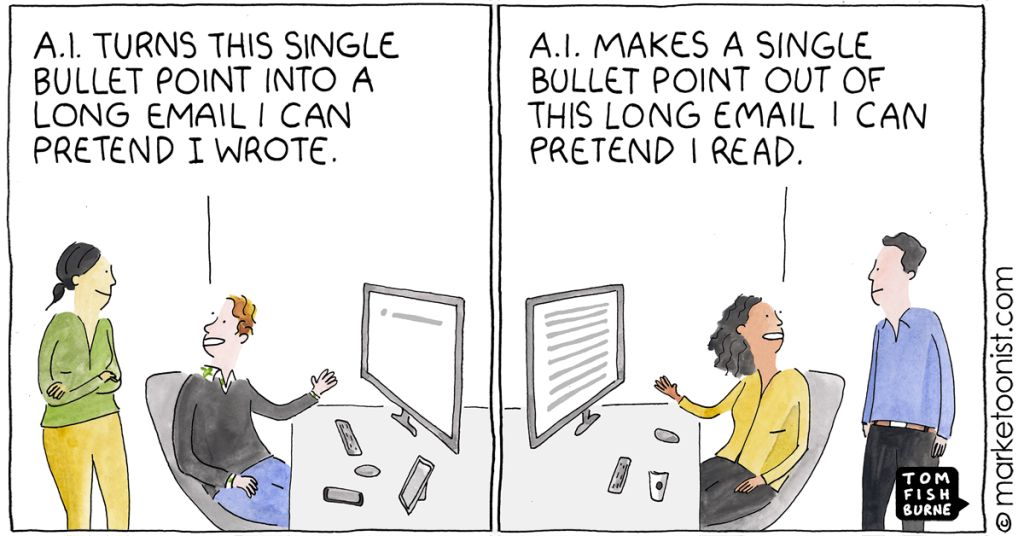

Ironically, our AI companions appear to be doing much better in areas we didn’t quite need or intended them to, as observed by this tongue-in-cheek tweet:

We were hoping AI could take the heavy load off our shoulders, so that we could enjoy more pleasant pursuits, but so far it’s been quite the opposite.

AI tools like Stable Diffusion, Midjourney or Dall-E are able to generate impressive art or highly realistic images on the basis of simple text prompts, like these “photos” of Pope Francis in a winter jacket which went viral a few days ago:

Or this retro photography from communist China showing things that never happened and people who never existed:

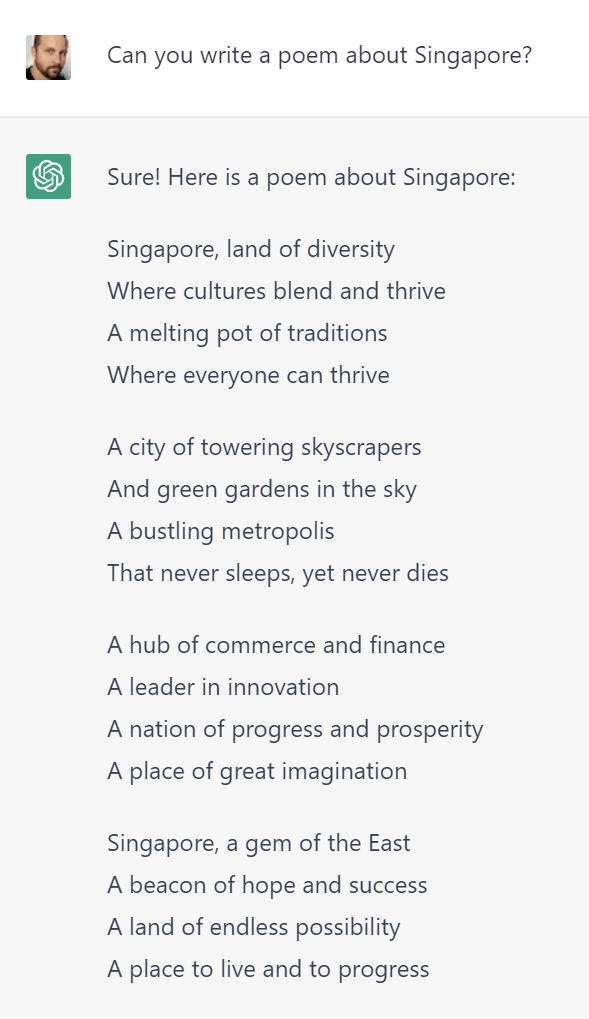

Meanwhile, ChatGPT can quickly churn out any number of poems or prose about anybody and anything (like Singapore).

Of course, it isn’t exactly a Nobel prize candidate, but that’s the thing about creative pursuits — it doesn’t have to be.

And yes, you can occasionally find glitches in some of the images but, again, they do not have to be perfect and any error is quickly visible to the naked eye. This makes it easy to correct them, unlike potentially made up information you have to confirm the validity of.

Areas where errors are non-critical is where AI excels.

But it also means that humans are still necessary to understand where those errors may have been made and correct them.

Undoubtedly, it is going to improve our efficiency in many tasks (like graphic design or coding), but it’s not likely to completely replace us.

At least not anytime soon, as it would require a far greater accomplishment than algorithmic output of plausibly sounding sentences.

For all the hype about artificial “intelligence”, we still have quite a way to go before we can use the term without disclaimers.

Featured Image Credit: bennymarty / depositphotos