Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

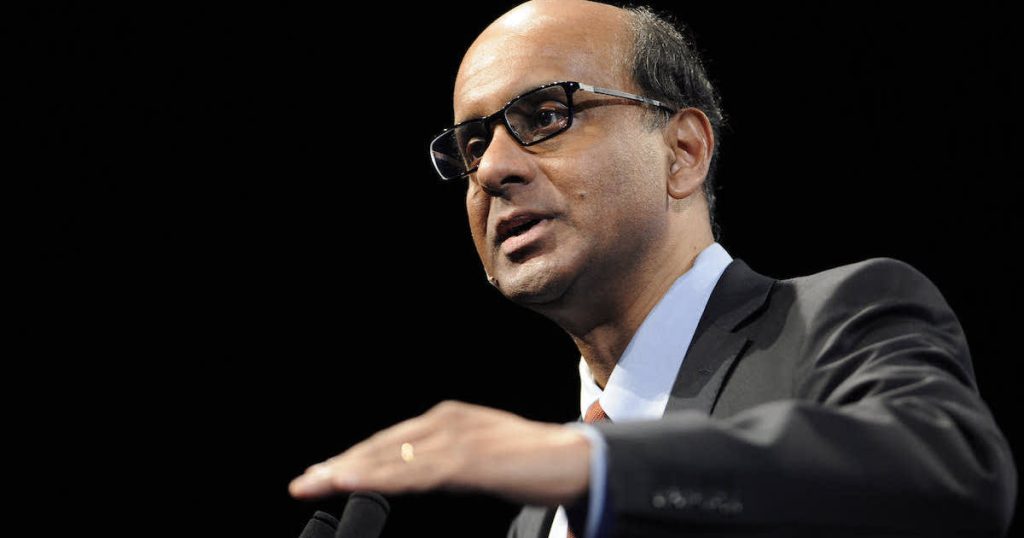

Singapore is going to pick its next president in a few months’ time and it seems that it might be another walkover, as the frontrunner to taking up residence in Istana is probably the most well-liked and respected politician in the city-state — Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam.

However, while people are wondering if he’s even going to see any challengers (and who might that be, as George Goh, founder of Harvey Norman, doesn’t meet the criteria to qualify automatically), it struck me that by the time he leaves the office (presumably after two full terms) Singapore might not need a successor.

It’s hard to see who could defeat Tharman in a popular contest and given his age, 66, he could easily hold the role for 12 years, until 2035.

By then, both Singapore and the world could be a very different place, given the current pace of technological innovation.

It may leave the importance of presidency either greatly diminished or even push it into obsolescence.

Governance by algorithm

The subject of outsourcing some or most of national governance to smart machines, supercomputers, algorithms and/or artificial intelligence is not new, but for the first time ever, we’re seeing technology acquiring capabilities that may permit this to happen within our lifetimes.

Being a politician is, after all, just a job — and no job is immune to technology, particularly one that is governed by codified laws, many of which could be easily translated for machines to understand and enforce without political or ideological bias.

The President’s role in Singapore is largely ceremonial, but it’s been also handed a few tasks of national importance — including safeguarding national reserves (and granting permission for them to be used in times of need), overseeing Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, as well as confirming appointments to select top administrative roles.

Thus far, this arrangement has worked well — but all it takes is to observe politics in other countries to understand that it might not always be the case.

Singapore is rather an exception than the rule in how countries are managed, with frequent conflicts between different branches of government all over the world.

Ultimately, how the laws are applied depends on people — ever the corruptible species. It doesn’t take much for the laws that were supposed to protect the nation to be used against it.

Let’s say a situation arises in which Singapore’s president is at odds with the government. He may block legitimately necessary access to reserves during another crisis, simply to undermine the cabinet, while claiming to be doing his job.

Conversely, a populist president, in cahoots with an equally populist ruling party, could greenlight spending of reserves even if there is no objective need to do so (but it may be politically expedient to give voters generous handouts ahead of another election).

The whole mantra of the president acting as a guardian of the reserves could quickly go out of the window.

Wouldn’t a superior solution be to simply set algorithmic conditions for access to them by the government? Objective data points like GDP growth, unemployment, inflation or budgetary deficit that is not fuelled by excessive discretionary spending.

Provided certain conditions are met, the government of the day would be permitted to access a certain amount of money from the reserves, entirely removing the ideological or political component from the process.

Nobody could accuse an intelligent machine of bias.

Elsewhere, given the small size of Singapore and how much data about it is already collected, how far are we from being able to trace corrupt practices or cybercrime with the help of AI, greatly reducing the risks of abuse of power by humans?

In fact, most legislation is written in a way that follows a very basic conditional statement of a simple algorithm: IFTTT (If This, Then That) — if certain conditions are met, then the following rules apply.

Thus far, the obstacle to deploying automated AI solutions in governance or law was our lacking ability to track most aspects of residents’ lives, business, health, education et cetera.

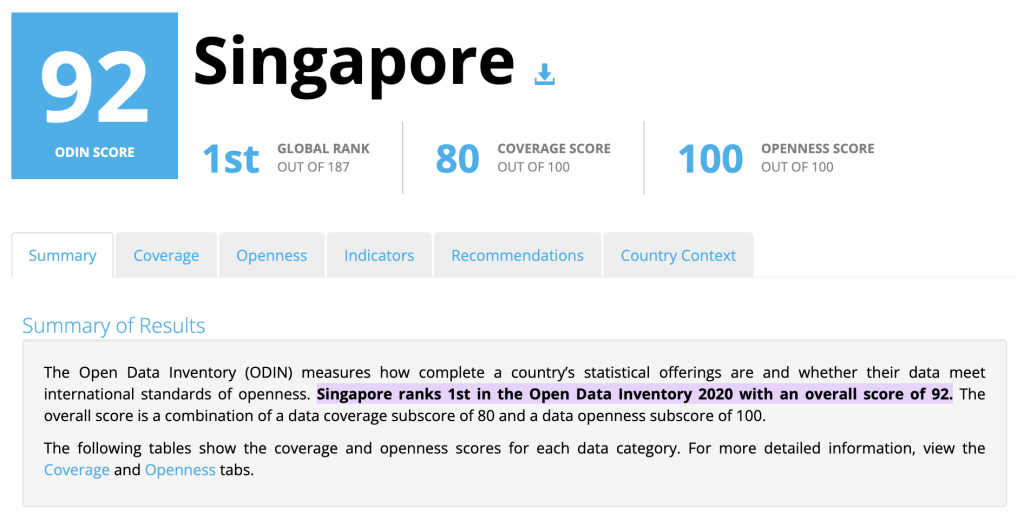

But that is changing rapidly, with more and more data not only being digitised, but becoming available in real time — and Singapore is already at the forefront of this shift.

Not only political office holders are going to fall under the pressure of technology, but thousands of people in public administration as well.

Fewer decisions are going to need human evaluation, as intelligent algorithms are going to be able to make them using the massive pool of information gathered about us, far more quickly (near instantaneously) than a human could look it up.

Tracking criminals (both in the real world and on the web), flagging suspect transactions, qualifying immigrants for visas, monitoring health of individual citizens or educational attainment of their children — all could very soon be automated and managed by well-trained AI models.

Of course, humans are still going to be setting the rules (at least some of them).

For example, it may be impossible for a machine to make a strategically sound choice regarding national defence, diplomatic relations with dozens of other states or domestic social, ethnic and religious harmony.

Humans will also be charged with determining the specific performance factors that national governance should pursue — in terms of things like financial sustainability, housing affordability or employment opportunities.

But it will be up to machines to provide the answers and do most of the work, just like today we are already asked to enter mere prompts into tools like ChatGPT or Midjourney and they provide us with the best currently possible output.

Human face of an AI industrial complex

Ironically, if the office of the president is going to survive, it will not be because of its importance to national governance but human affinity for decorum at the leadership level.

Ceremonial functions — the very same that many sneer at even today — are the only area where AI or any other form of automation is completely unnecessary and pointless.

Technological progress may reduce office holders to shaking hands and giving speeches, while smart machines ensure the country is running well every single day, under greatly reduced human supervision.

But if representing the nation remains the only role for the president, why not just keep it with the prime minister (who typically attends all of the most important gatherings anyway)?

Despite few real powers, the institution of presidency was meant to provide some safeguards in the most crucial aspects of governance, so that an independent office holder would have a few tools of last resort to limit excesses of an irresponsible cabinet (should there ever be one).

But if these functions are one day replaced with objective, data-based, ideologically and politically agnostic, intelligent machine or software, what would the president be needed for?

The answer may come sooner than we all expect.

Featured Image Credit: Munshi Ahmed | Bloomberg | Getty Images