Disclaimer: Any personal opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

Channel NewsAsia published yesterday (August 16) a three-part interview with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong on YouTube, as a part of documentary Singapore Reserves Revealed, in which he speaks about the inner workings of reserve management — what constitutes them, how they are spent, or whether they can be touched at all.

I encourage everybody to watch it, of course, but given how frequently I write on the topic myself, I thought it would be useful for those who prefer to read to focus on the most important points concerning every Singaporean directly:

- What constitutes reserves and how big are they?

- Can we spend more money from them?

- Don’t we have enough already?

What reserves?

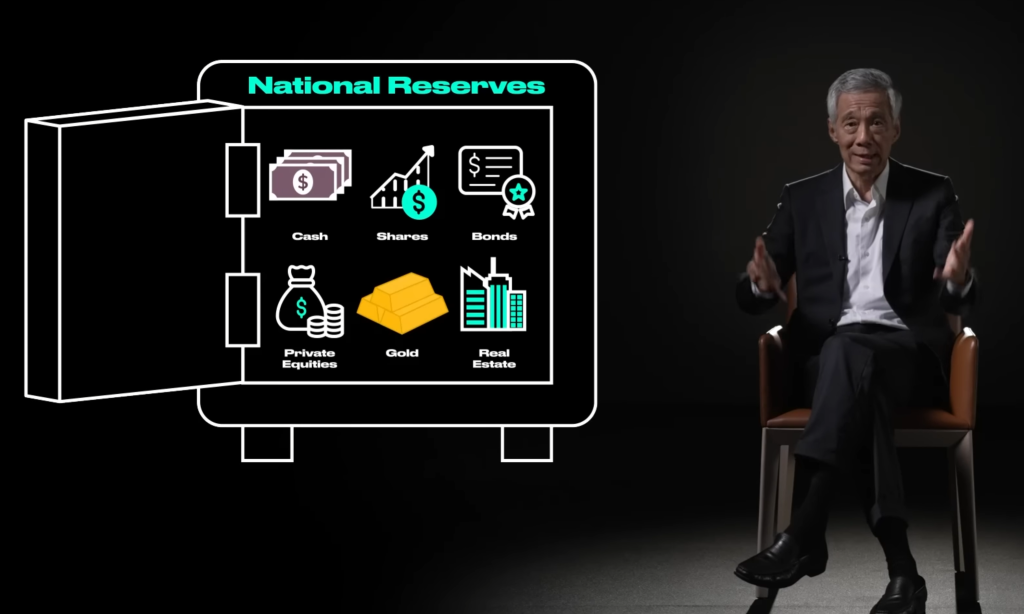

Part of the challenge in discussing the topic of reserves in Singapore is that they consist of many different types of assets, which aren’t used in the same way.

In the broadest sense, it’s everything that the country has that it can lean on in the time of need — cash or equities managed by the likes of Temasek or GIC, foreign currencies and gold at the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), or real estate and land owned by the government.

How much money is there?

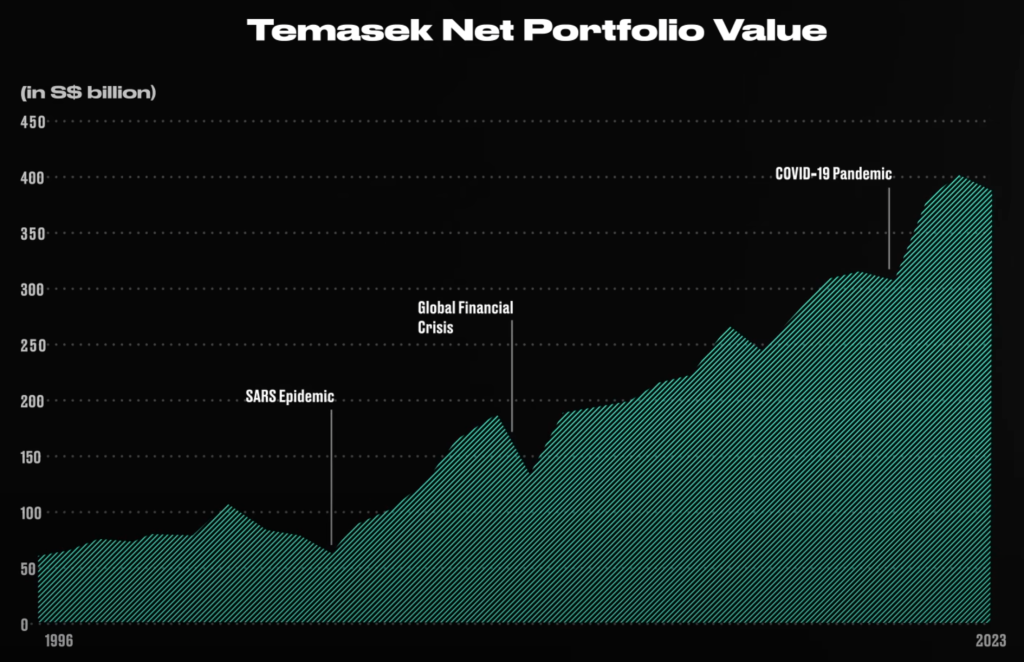

While usual conversations revolve around the assets held by MAS (S$452 billion worth of foreign currencies and gold), Temasek (S$382 billion) and GIC (unofficially estimated at over S$1 trillion under management, which indirectly includes funds from the Central Provident Fund), Singapore remains resilient in the face of potential severe crisis.

This resilience is bolstered by its substantial tangible assets such as land, buildings, ports, airports, and more. The total value of these assets cannot be reliably estimated since if any were to be sold, the circumstances of the sale would affect the end price.

Another issue is that, even under normal circumstances, the presented values are not equivalent to how much could actually be used to finance local spending needs. Even financial reserves have different origins which determine how — or even where — they can (or at least should be) be spent.

Unlike what many people think, reserves are not a vault full of gold that could, potentially, be drawn from at will.

For example, GIC was founded as a manager of excess foreign reserves held by MAS — which means the funds both organisations deal with are not denominated in SGD (so they can’t be spent directly in Singapore).

Because the city-state had been so popular with foreign investors for many decades, they needed to exchange their foreign currencies (chiefly USD) into SGD to do business on the island.

Those foreign currencies end up with MAS (which issues the SGD) and can be used to control the exchange rate of Singapore dollar versus other currencies (the bank can, for instance, use the USD to buy SGD, to reinforce its value if it feels it’s too low).

As Singapore had remained successful for many years, the accumulation of foreign currencies fast outpaced the policy needs of MAS. There was no reason to keep so much of the money in the bank doing nothing, so GIC was formed in 1981 to profitably manage that surplus abroad.

But, essentially, these funds are still an extension of foreign reserves and cannot be directly spent in Singapore since they are denominated in currencies of other nations. Any sale of these assets and exchanging them for SGD to finance anything at home would immediately impact the international exchange rates as well.

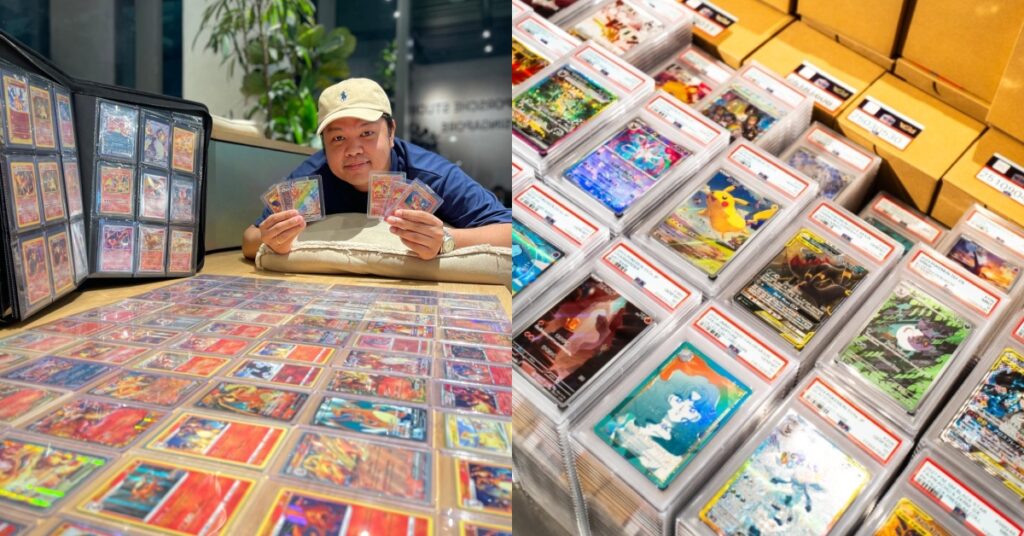

The case isn’t simple even for Temasek, which keeps much of its assets in Singapore (originally all of them, given that it started as a holding manager for GLCs in 1974). While the value of its portfolio has increased by over six times since 1996, unwinding parts of it would often mean selling a stake in local companies — like Singapore Airlines or Singtel.

So, if you wanted to draw from Temasek’s pool, you might have give up ownership of some of the country’s largest, most successful, but also most economically important enterprises.

In essence then, while Singapore has over a trillion SGD worth of reserves managed by GIC, MAS and Temasek, and billions (if not trillions more) in other tangible assets owned by the state, those figures are not really as meaningful to average Singaporeans as this one is:

How much can we actually spend?

Even today, S$23 billion — or around 20 per cent — in Singapore’s annual budget comes from reserves: Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC) to be precise.

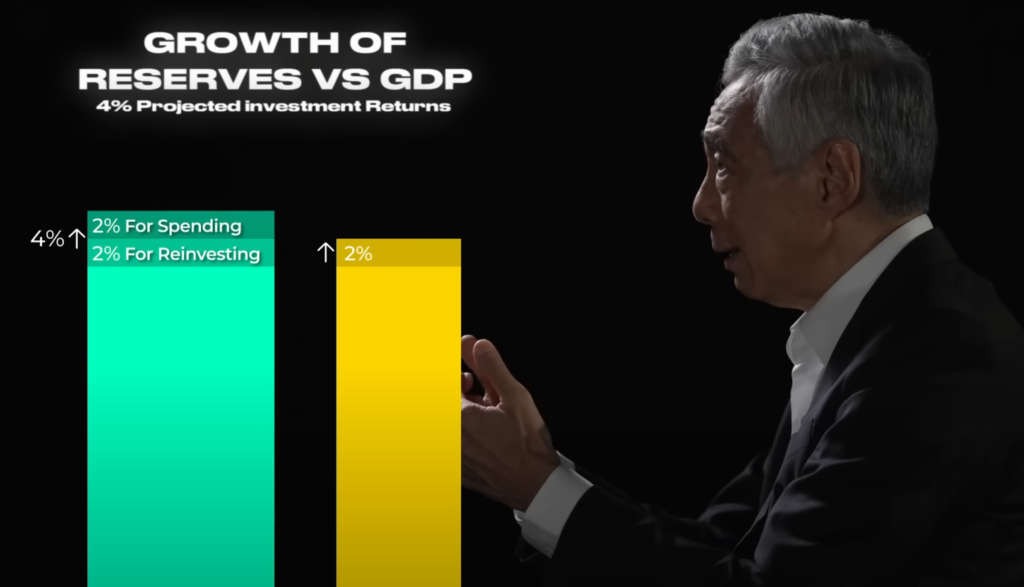

NIRC equals 50 per cent of average long-term return rate on assets managed by MAS, GIC and Temasek. The remaining 50 per cent is reinvested back for the future.

Could Singapore spend more than that?

Not really — at least not without undermining long-term financial security of the country.

You see, those accessible, liquid reserves only serve their purpose if they at least keep growing at the same pace as the local economy.

In the interview, PM Lee explains that GDP and reserves currently expand roughly in line with each other, after subtracting NIRC, which is diverted to the budget. This means that out of four per cent average return on reserves, two per cent is reinvested and it’s a comparable level to roughly two per cent annual growth of GDP for a developed nation that Singapore now is.

With GDP of over S$500 billion SGD and reserves at MAS, GIC and Temasek worth over S$1 trillion, their proportion to GDP is in the region of 2:1. This means that half of an estimated four per cent annual return on those reserves, amounts to, as I explained, 20 per cent of the annual budget.

But if GDP keeps going up and reserves cannot keep the same pace, then a larger proportion would have to be drawn to prop up the economy in case of another crisis such as Covid.

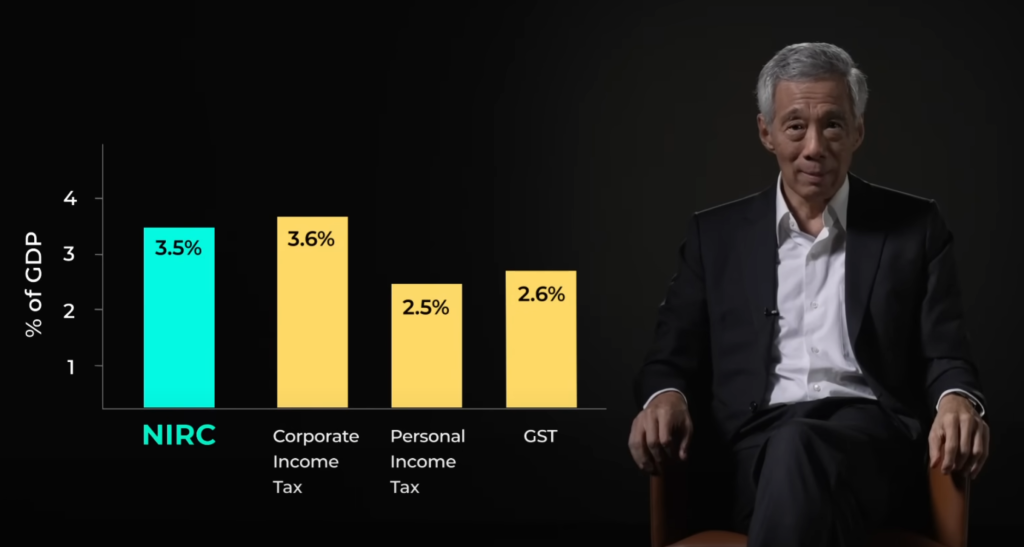

A similar fate would await NIRC which, at 3.5 per cent of GDP, is about as big of a source of revenue every year as corporate income tax and larger than personal taxes or GIC. If reserves do not grow in line with GDP, then NIRC’s share would begin to drop, necessitating raising taxes to make up for the shortfall.

In the absence of reserves, Singapore would have to double its Corporate Income Tax or more than double its income taxes or GST, which PM Lee estimated to be at least 10 percentage points more — not nine per cent, introduced next year, but 19 per cent (comparable to the VAT rates in Europe, for example).

In reality, it could be even more than that, since tax revenues tend to drop off as rates are raised, so less money is collected for each subsequent percentage point.

In other words, Singapore is already profiting from reserves each year, but objectively speaking, cannot draw any more from them without hurting their purpose. It already is at the reasonable limit.

This brings us to the final question:

Can we ever have enough?

The short answer is no.

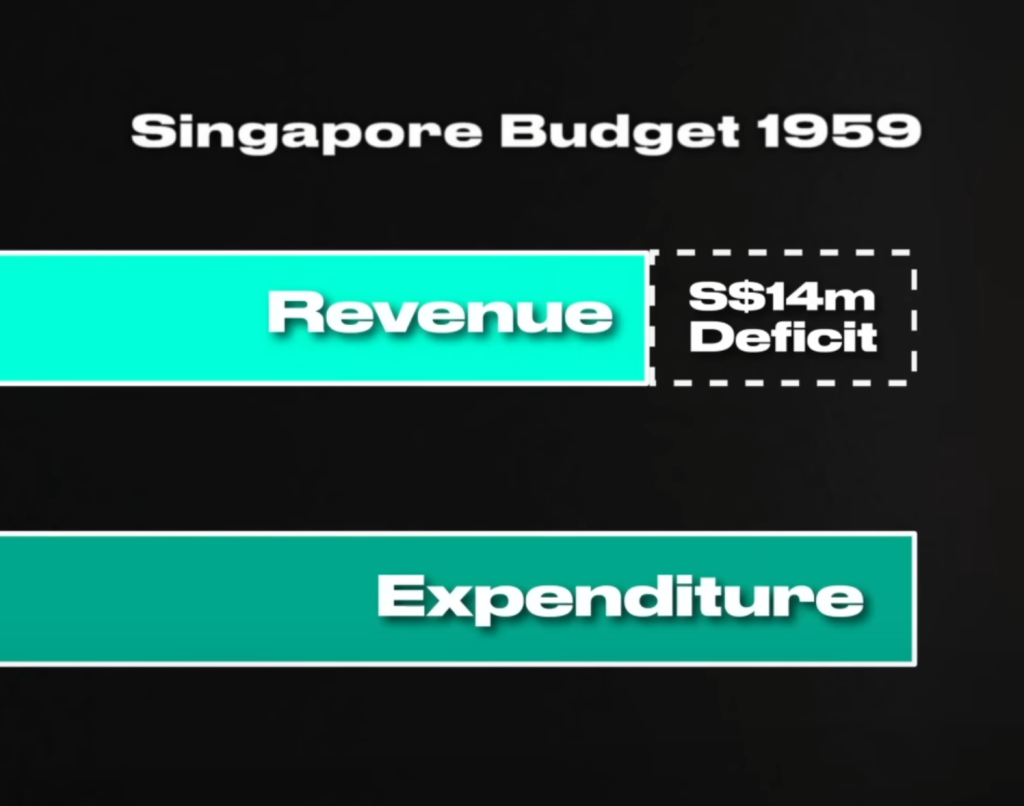

PM Lee brought up an example of early, pre-independence Singapore budget of 1959, where the deficit was S$14 million. Sounds small today (even if we account for inflation), but it was a lot then. Obviously, if the island had reserves it could draw from, it would not have been as big a problem.

Most countries solve it by taking on debt. They borrow money and pay interest to lenders just to finance their regular spending. So, not only do they make less than is necessary, but the shortfall is becoming more expensive because of those interest payments.

This has become an economic snowball for many nations, which keep borrowing only to run even bigger deficits (as they have to keep paying more in interest), necessitating even more external financing, until they can’t pay their debts anymore and face economic implosion (like several European countries in the aftermath of 2008/09 crisis).

No amount of money will ever be enough to protect Singapore from a similar fate.

At the very least, as I mentioned before, reserves should keep growing in perpetuity at a pace equal to GDP growth. Ideally, it should be more, so that they become a larger source of revenue in the future.

However, building them up today is much harder than it was in the past, when Singapore was a developing nation, quickly catching up to the rest of the world at a pace of eight to 10 per cent annually.

Since it started managing its assets so early on, it was able to benefit from huge impact of compounding of high return rates on its various investments — both in and out of the country.

However, doing so now would not yield nearly as strong results. It’s not just because Singapore is a mature, developed economy, which can only grow so much each year, but it’s also due to the fact that it’s more difficult to deploy vast sums of money at a high profit.

It’s easier to find an opportunity that returns 10 or 20 per cent per annum on an investment of a million dollars than it is for a billion, not to mention hundreds of billions of dollars.

This is why, despite having amassed such vast wealth, the job of managing Singapore’s reserves is not — and will not ever — be done.

Featured Image Credit: CNA via YouTube