Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

Between 1517 and 1528, decades before Nicolaus Copernicus shook the world with its heliocentric model of the solar system, proving that Earth revolves around the Sun and not the other way around, the Polish astronomer — a polymath, really — observed and described an economic phenomenon which, in later years, became known as Gresham’s law in the Western world (after an English financier and contemporary of Copernicus).

500 years later, it continues to be relevant, though not in a domain Copernicus was likely to have predicted in his time — Artificial Intelligence (AI).

His conclusion, which you likely have heard somewhere before, is that “bad money drives out good money out of circulation”.

To be fair, Copernicus wasn’t the first to observe it, but he was the first to rigorously explain it and suggest mitigating actions.

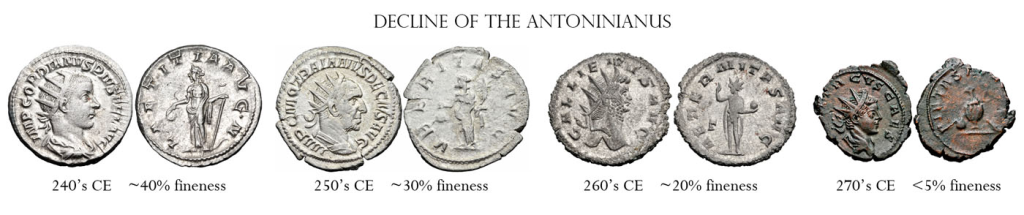

This was a problem in the past when value of currencies in use was based on the proportion of precious metals like gold in silver they contained.

Reducing their content while maintaining face value was used either by individuals, as an act of fraud, to steal a little bit of every coin (e.g. by shaving it off, collecting the precious material), or by governments themselves, in an attempt to mint more money than their gold and silver holdings would permit.

Both good and bad money comes with the same nominal value, but only good money accurately reflects the value of the component metals. Bad money, on the other hand, uses cheaper replacements — like copper or nickel, instead of silver and gold.

In a system where both are allowed to circulate, people quickly learn which money is intrinsically more valuable and keep it for themselves, since the gold or silver it contains can be melted and sold at a higher price later on.

As a result, good money is driven out of circulation entirely, as people will always act to maximise their personal benefit.

This observation applies in some form to all human economic activity, and generative AI is no different — though for certain reasons, the Gresham-Copernicus law is a bit more relevant to it than other things, as I explain below.

Less art in art

First of all, the threat of dilution of value by smart algorithms is obviously not good news for creators/artists. It could, however, be absolutely disastrous for all of us, as it is likely to affect not only how pretty pictures are made but the quality of all information we consume.

When it comes to creative work, what generative AI does, especially in creating images/graphics or video (but also text), is it greatly reduces expensive, time-consuming human contribution, without reducing the utility of the work.

In consequence, you’re getting “less art in art” — just like you would get less silver or gold in your money — but nobody cares as long as it’s not noticeable (which in most cases it is not) and serves its purpose.

This, however, is applicable to any good or service. Reducing costs by moving production abroad or employing machinery to increase output works just like using AI to create an image of a cat or a piece of promotional text for a marketing campaign.

Where the consequences reflect Copernicus’ observations more closely is in regard to things that are in perpetual circulation (rather than individual, commercial transactions) — chiefly, information.

We consume a mountain of it every single day on social media, news outlets, Wikipedia, and billions of websites we can search through using Google, as well as in more traditional, paper form too (which isn’t immune to the impact of AI either).

Generative AI is already advanced enough to dwarf the volume of human output on any topic in existence, without us ever being capable of verifying its accuracy on our own.

What is even worse, machines are also able to learn what sort of language and presentation is superior at attracting human attention (like generating clicks to a website). This means that not only is AI able to create garbage at will, it can also learn how to make it seem like it’s perfectly correct and then sell it to us.

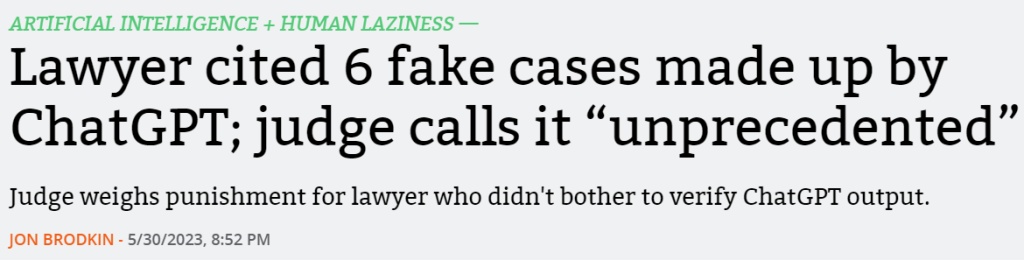

In fact, it can add layers to the lies making up fake references to non-existent source material, as one unfortunate lawyer learned the hard way recently.

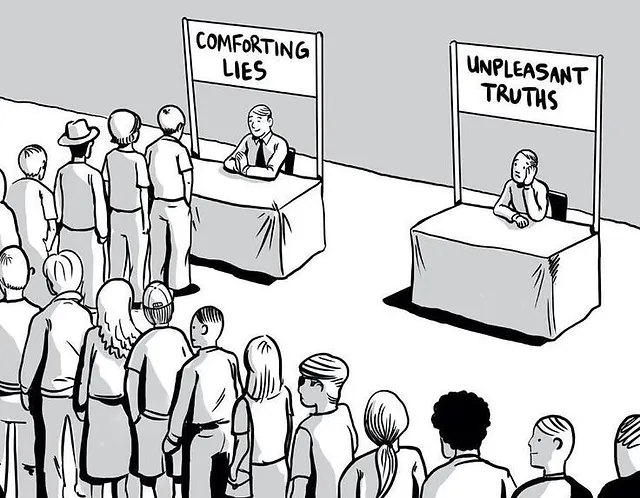

When confronted with two things that have an appearance of accuracy, most people will choose the one that is more appealing to them.

In essence, then, AI can debase the value of information on any topic, pandering to our expectations or subjective beliefs, driving unpleasant but accurate facts out of circulation.

This is, of course, due to human nature — both among content consumers as well as creators using these tools to take advantage of us, since AI is ultimately just a technology serving particular interests of somebody who directs it to produce a desired output.

We like to have our convictions confirmed and others like to use (or abuse) it for their own benefit.

This may be done in order to make money, but it may also be used to mislead people on any topic of political, ideological, or even religious significance.

Model collapse

What’s worse, because generative AI is learning from the input provided, which includes the internet as well (where anybody can publish anything), the phenomenon described by Copernicus may lead to several rounds of progressive debasement of information, up to a point of near complete worthlessness.

Today, AI is learning from fairly accurate input material created and verified by humans, but within years, machine-generated content is likely to flood the web, becoming treated as a source, cyclically reprocessed by large language models leading to what is called model collapse.

Model collapse refers to a degenerative process where, over time, AI models lose information about the original content (data) distribution. As AI models are trained on data generated by their predecessors, they begin to “forget” the true underlying data distribution, leading to a narrowing of their generative capabilities.

While this is an intrinsic flaw of machine-learning algorithms, it is exacerbated by our own propensity to gobble up falsehoods which, in turn, become more widely shared, gradually drowning out the truth, and skewing language models towards learning from increasingly mangled content.

Putting the genie back in the bottle

I think I can state without any controversy that demand for the truth isn’t really high and it’s our nature to favour information that we’d like to be true, even if it’s not.

This is accurate even today, when we still have fairly good tools allowing us to do quick fact-checking on most of what we read or see online. People spend most of their time voicing opinions, but rarely check them against reliable information.

With AI, those misguided opinions may soon become a part of the source material they were never supposed to be and gain traction because many people will find them appealing.

Short and long-term consequences of these phenomena are really difficult to predict.

In the near future, it may lead to complete chaos out of which new order will have to emerge in later years as the value of most information — particularly available online — may completely collapse, preventing us from knowing what is true and what isn’t.

Ironically, it may lead to reduced use of technology and perhaps even a return to physical media produced before the AI boom, as they become perceived as more reliable.

These observations of a possible implosion of the digital world as we know it are not dissimilar to Copernicus’ analysis of economic consequences of currency debasement which, in his view, had caused entire countries and nations to collapse in the past.

The root of the problem was the pursuit of profit from minting money, that Copernicus proposed to erase. Its nominal value should match the intrinsic value of materials used, nothing else.

Coins should be a means of exchange, not a way for the authorities to enrich themselves, since that creates an incentive to debase the currency. And while it may temporarily boost national income, it has knock-on consequences, as the same motive is passed onto the public, driving good money out of circulation and a new round of debasement is required to achieve a similar effect, ultimately leading to destruction of all value with time.

If the profit incentive is removed, there is no reason for anybody to alter the coins and they retain their worth over the long term.

We have achieved this in the modern world by detaching value of the currency from any commodity, controlling it instead by law, foreign reserves (allowing us to balance international exchange rates) and allowing the free market to determine its value on the basis of the strength and attractiveness of local economies (this is why US dollar — or Singapore dollar — retain their value very well).

Unfortunately for us, applying this principle to AI is going to be extremely difficult, if not impossible, as it would require most businesses to forgo profit-seeking (which would also destroy the incentive to develop AI tools) and lead to creation of some form of centralised authority placed over the content machines are fed and the output they produce. A Central Bank for Information.

Besides being difficult and impractical legally, some would argue that it infringes on freedom of expression, leading to comparisons with Orwell’s 1984, where the Big Brother decides what people are allowed to know — and these parallels and fears would not be entirely unfounded.

Given all that’s going on in the world, how many of us would trust such an entity to be impartial and accurate?

Looks like the best we can do is trying to fight AI with AI.

If we can’t control all inputs and outputs, then we can at least allow such a centralised authority to act as an advisor, providing context to the information we consume, without having the power to outright prevent any from being published.

It could be an AI-powered fact-checker based on human screening of the content it is fed, not too dissimilar to X’s “community notes”, which provide additional information without the need to resort to blanket censorship.

While not ideal, AI could take this concept to a new level, blunting somewhat the harm which could be done by unbridled machine-learning algorithms placed in the wrong hands.

Featured Image Credit: Depositphotos