Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

Over the past few days, Singapore has been consumed by the rather unexpected outrage following LTA’s announcement that EZ Link cards would cease to function from June 1st, when everybody who isn’t yet on the new system, SimplyGo, has to transition.

Despite the fact that two-thirds of Singapore commuters are using SimplyGo already, opposition from the remaining minority has been very strong — likely surprising the decision-makers.

There seems to be a gulf in understanding what it is about, between those who don’t want to part with EZ Link and those who have already been blissfully unaware of how much it could matter to someone else, while they themselves have for years been using the new system already.

Comments critical of the protesters frequently seem to suggest that it’s just the resistance of those who lack technological savvy (presumably of an older age) and that progress should not be sacrificed just to keep a backward minority happy.

This is both inaccurate and unfair.

Friction and uncertainty

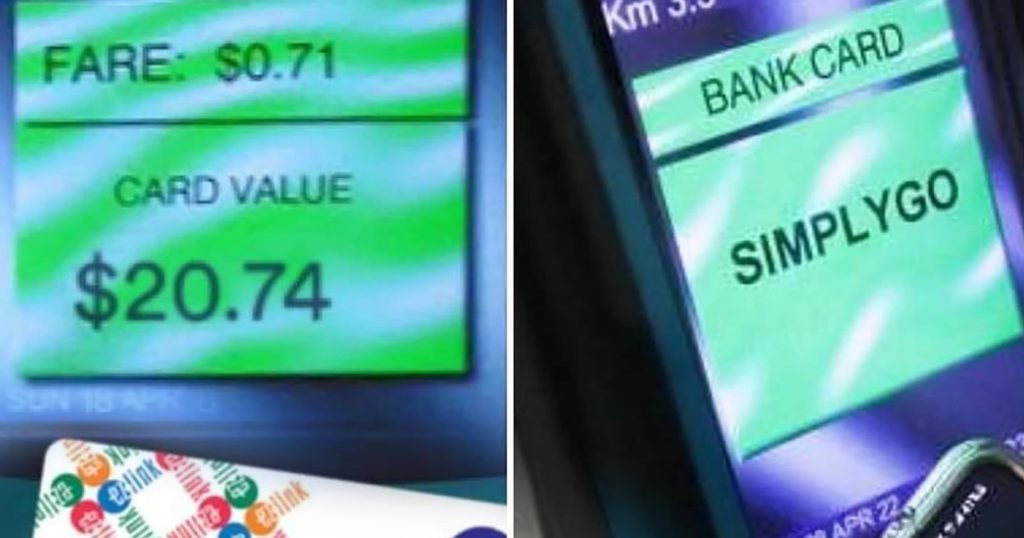

The main source of unhappiness is the disappearance of fare and balance information that is displayed upon tapping the reader at MRT gates or on buses. It provides a quick and easy way to track spending as you go along, and it also warns you when your balance is getting low, so you can top up your card the next time you’re travelling.

LTA and the “progressives” in this conflict point out that you receive this information in your mobile SimplyGo app, and you can even configure it to send you notifications about your expenses and reminders to add more money to your card.

Since almost everybody carries a smartphone in their pocket these days, it should not be a lot to ask people to just keep track of their travels there.

LTA has also clearly recognised that the group least competent in using smartphones might be the elderly, so it has exempted them (and other concession card holders) from the shift to SimplyGo.

It is, probably correctly, assumed that everybody under the age of 60 should be able to use their phone.

So, why are so many people up in arms about it?

Unlike some of the critics of LTA try to argue, the transition was not rushed or lacked planning. These things don’t happen overnight, after all.

It did, however, lack understanding of the user experience of different segments of commuters.

I can empathise with their concerns since I have always used EZ Link myself and enjoyed its simplicity. Coming from Eastern Europe, I have also faced financial misadventures in my younger years, which is why I know first-hand why it is important to track how much you spend — and how much money you have left on your card.

This may be poorly understood by those who pay with their banking cards or have set their SimplyGo app to an auto top-up, so they never have to check the balance. They can afford not to care.

However, while public transit in Singapore is very cheap, for a developed country that it is, even those small charges can add up for people who are cautious about spending.

Yes, you may indeed check your fares in the app, but the ability to view the charge at a glance while leaving the bus or MRT served the role of simple live tracking of expenses throughout the day.

Opening your phone up and sifting through competing notifications from different apps just to review your fares on SimplyGo adds considerable friction to the experience. Friction causes annoyance, hurting user satisfaction.

Meanwhile, lack of information increases uncertainty, causing further stress to customers.

Instant confirmation of the charge provides reassurance that you correctly tapped out when leaving the bus and that you didn’t pay the full fare. On the MRT, it confirms that you paid the correct fare, and if you suspect you may have been charged an erroneous amount, you can immediately approach the help desk then and there.

How many people want to go through the register of their rides when they return home?

Those who can afford not to care about being occasionally charged a buck or two more than they should are unlikely to understand those who worry about paying their bills.

LTA has grossly underestimated the importance of these details to a fairly large group of people. This is why they’re so angry now, not because they don’t know how to use a smartphone.

The changes are causing them distress, and trying to dismiss it doesn’t solve anything.

One card to rule them all?

As if that wasn’t enough, LTA’s communication isn’t helping. One of the chief arguments for the switch to the new system was that it could eventually replace the legacy ones, while adding new features.

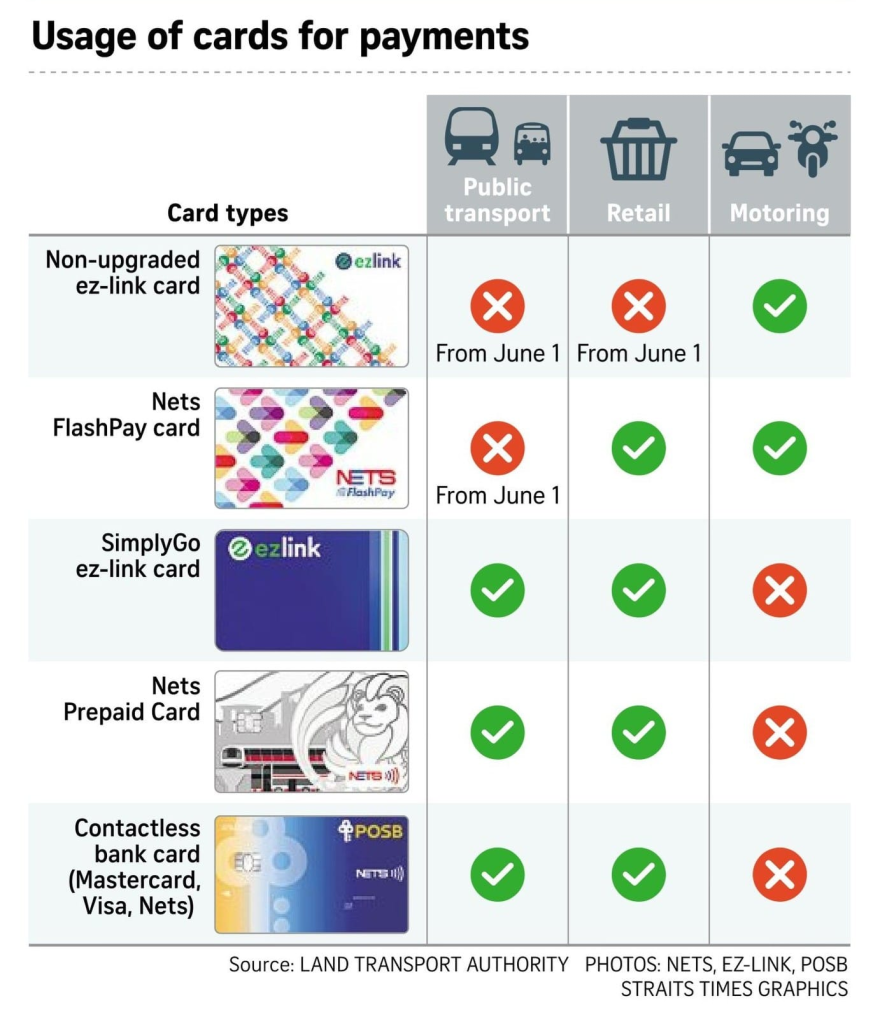

But, as it happens, beyond exemptions for concession cards (the existence of which is going to keep some old systems in operation for an undisclosed period of time), the “upgrade” also disables the ability to pay with EZ Link in stores, while not extending SimplyGo to motoring charges, meaning that instead of one card customers will now have to use two.

And that EZ Link is still going to be around, after all. How is that considered a step forward?

This table doesn’t even include concession cards, of which there are also two types (SimplyGo and old CEPAS).

You should go back to the drawing board if you have to produce charts instructing clients how to use multiple different cards instead of just one, to pay for your services.

Less is more.

And even more friction

Finally, there are questions about the smoothness of operation of the SimplyGo system as a whole.

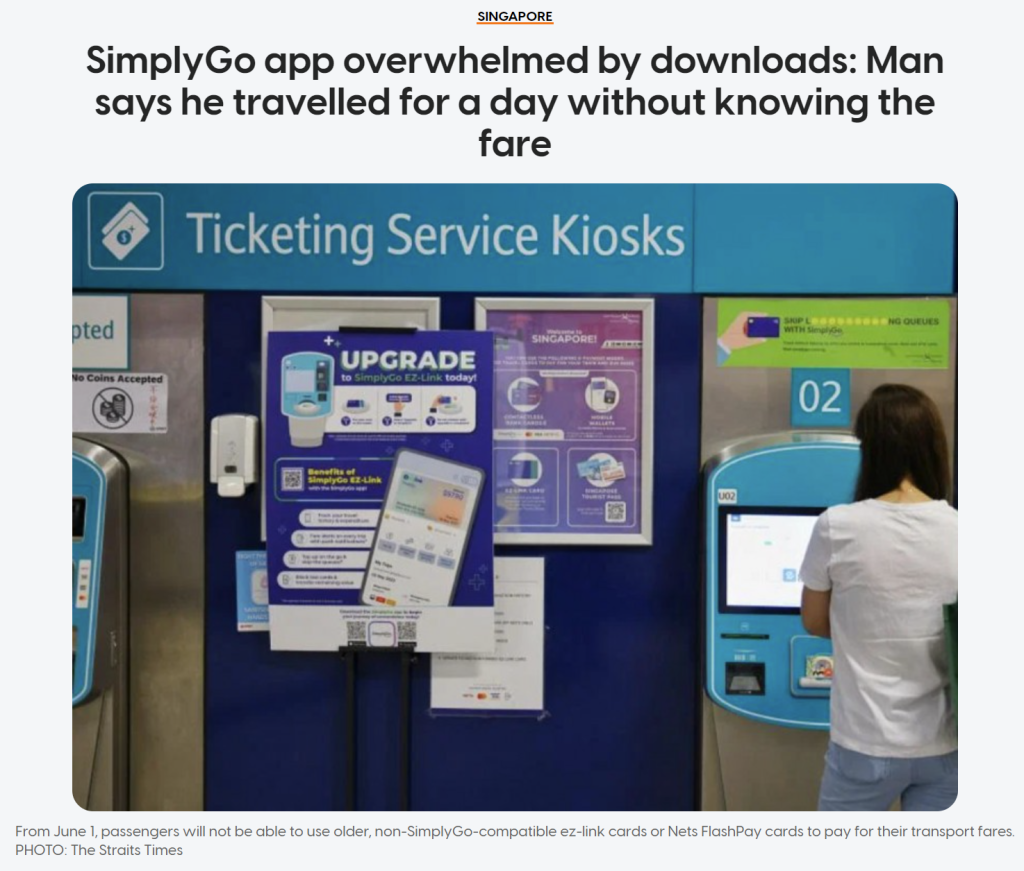

First of all, there were the severe difficulties that thousands of users faced when trying to upgrade their EZ Link to SimplyGo following the announcement on January 10.

Not only was the mobile app crashing, but the upgrade process often failed even at ticket offices and dedicated machines. It’s easy to blame it on overwhelming demand – but wasn’t it the role of the LTA to plan for an easily predictable usage surge?

It certainly doesn’t help in building trust for the new system. Even if we are generous and recognise that every new launch has teething issues, haven’t we all built enough experience over the years to get ready for it? Shouldn’t it be a bit better each time?

Secondly, there’s anecdotal evidence of problems with both registering charges and top-ups, which some people reported were having delays between minutes to hours.

In other words, even if you wanted to use the mobile app to check how much you paid for your trip upon leaving the MRT, the information may not be there yet. Some claimed it only appeared in their accounts the following morning.

One commuter reported having checked the app before travel, seeing it had a small but sufficient balance, only for it to be deducted to pay for past fares sometime later, rendering him unable to board the bus he was waiting for.

Subsequent top-up took several minutes to register, keeping him stuck at the stop, not knowing when he was going to be able to go home.

Again, perhaps these issues can be rectified with technical fixes, but it’s really concerning to see them in a system that’s been in development for 5 years and has reportedly already onboarded a majority of commuters since 2022.

How can there still be technical hiccups at this point?

Because, let’s remember, SimplyGo no longer stores information on the card — it’s all on the servers somewhere else. Which introduced a single, major point of potential failure.

Yes, thanks to this design, we can have remote top-ups, the ability to disable a lost card, control over multiple users and so on. But it’s only useful when it works. And it doesn’t help public impressions when it spectacularly crashes on the first day.

We don’t need avoidable stress

What it all boils down to is stress. Most of us are already stressed enough not to need to now worry about uncertainties and annoyances in using a new system that doesn’t deliver truly ground-breaking advantages.

Companies all over the world spend tons of money to refine how they present information to customers, because a reassured customer is a returning one.

Perhaps this is the origin of the problem with SimplyGo — public transit is an essential public service that people have to use no matter how friendly the payment system is.

It seems to have been built around the goal of adding certain technical features, with inadequate effort to understand how the changes may be received by different groups of customers.

Moreover, as long as it was not compulsory, it attracted mostly people who didn’t care about some of the old features going away. The rest stuck to what they knew and liked.

But now they are being forced to do what they have avoided for so long; it perhaps shouldn’t be a surprise how unhappy they are after all.