Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

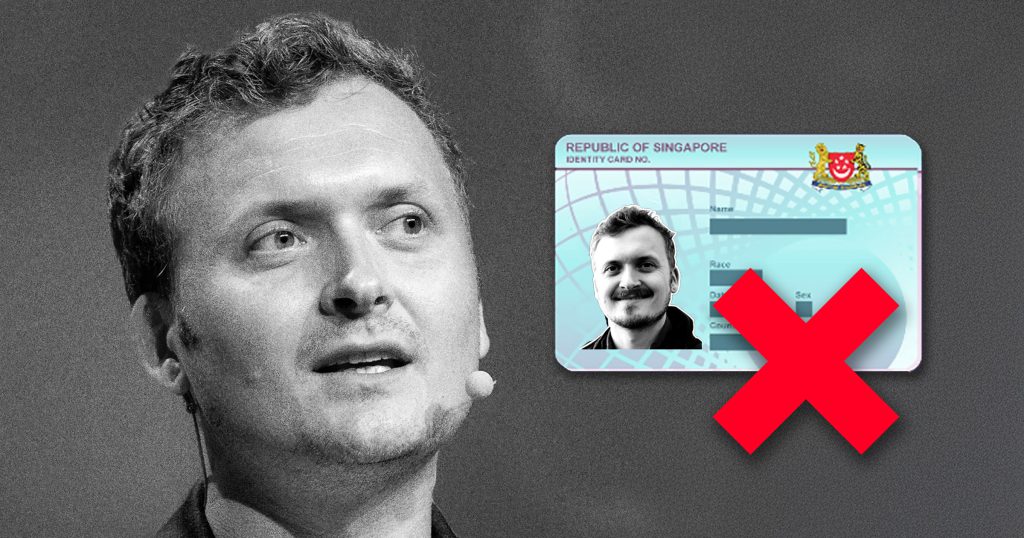

You may have seen it in the news a couple of days ago—a CEO of a Singapore-based crypto analytics platform, Nansen, vented his frustration about getting his permanent residency (PR) application rejected on X in a viral post that garnered over 2.7 million views and a few thousand responses.

Just got my Singapore Permanent Resident application rejected!

— Alex Svanevik ? (@ASvanevik) October 14, 2024

$88m capital raised

25+ jobs created

1 child born

Guess it wasn’t enough.

Where to move next?

On the face of it, his complaint may seem valid. After all, if you’ve contributed so much in economic value and jobs, and your family is here too (his wife is reportedly a PR already), then why would the country reject your bid?

Surely this would work very much everywhere else, especially in business-friendly jurisdictions, which Singapore competes with.

So, why was he rejected and what does it take to become a PR?

Permanent risks

Of course, my opinions are highly speculative, as Singapore authorities merely list some basic eligibility criteria and never say exactly why your particular application—whether for PR, Employment Pass or S-Pass—has failed.

With the exception of the Global Investor Programme, which imposes impossibly high requirements for qualification (like running a reputable company with a turnover of a few hundred million dollars in addition to a S$10M investment), but is otherwise formally structured, it’s not as simple as ticking several boxes.

This is mainly because Singapore is tiny and cannot take people in as freely as, let’s say, the UAE can (and does these days). Hence, applications are reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

Still, why would a pretty wealthy CEO of a multimillion dollar crypto tech startup be refused permanent residence here?

Let’s look at the hints in Singapore’s various policy stances and the benefits of permanent residence.

First, the city-state has been rather lukewarm towards all crypto investments.

It’s likely due to the fact that even after all these years the application of the technology has found limited credible uses and had its reputation tarnished by scams, bankruptcies, money laundering and so on.

If FTX could go bankrupt, no crypto company, no matter the size, is entirely beyond risk. By comparison, US$88 million raised for a startup isn’t exactly all that impressive, especially given Singapore’s financial hub status, with billions upon billions of dollars moving through it each year.

In other words, Singapore authorities have to assess not only what you have contributed so far but also the reputational risk you or your ventures may present in the long run, as you are granted far more liberty under a PR status.

Mr Svanevik currently runs his company on an Employment Pass. Despite its benefits, EP is a highly restrictive work pass that allows you to work for one specific company only (in this case, his own) and is subject to renewals every few years.

It’s not transferable and does not permit taking employment in any other businesses or setting up new companies. It’s possible to work for more than one, but each new position would require a separate EP application, allowing the authorities to control what a foreigner does in Singapore.

When you become a Permanent Resident, however, you’re granted complete freedom in that regard.

You’re largely equal to citizens, just without the right to vote and with some restrictions on state benefits. But you can start as many new companies as you want, and your residence permit never expires.

So, let’s circle back to Nansen.

While this particular company may present low risks (since it’s about analytics, not trading tokens), it is permitted to operate in Singapore, its boss can work and live in the country under the EP, the authorities may be concerned if any future ventures—in an industry they inherently distrust—would continue to be.

Of course, every business is subject to regulation, but rules alone do not eliminate all risks.

Now, let me be clear: this is not to suggest that Mr Svanevik or any other person, in particular, may be up to no good, but rather that the immigration administration has to consider whether he genuinely requires the benefits of permanent residence—and if the country can accept the potential risks associated with granting it to him (or anybody else).

Essentially, ICA is asking a specific question: does this person really need the PR?

Money isn’t everything

As Nansen’s CEO admitted his wife is a PR, and he didn’t suggest she’s wealthier or more successful than he is. This is because PR status is not about the money but how deeply rooted you appear to be in Singapore.

Of course, I do not know the specific conditions under which she was granted her blue IC, but she clearly appeared to be a safer bet.

Yes, if you bring millions of dollars and numerous jobs in, this may work in your favour—but do you really treat it as your home? Or will you pack your bags up and leave if things go south, for whatever reason?

Or even worse—will you take advantage of it and then flee, leaving the authorities to hold the bag while angry Singaporeans decry open immigration policies?

The city-state doesn’t need more money. In fact, it gets so much of it that it had to erect barriers to ensure it doesn’t become a haven for questionable behaviours and people.

Ironically, perhaps, a person of lower status may have a higher chance of succeeding in their PR application, given that they would depend on a local job, be married to a local spouse, have their family or children in Singapore, or even come from a neighbouring country like Malaysia—all of which provides reassurance they already are a well-embedded member of the society.

On the other hand, foreign entrepreneurs often raise more questions than they answer.

They have usually left another country already and are open to moving on to a more attractive jurisdiction if need be. Their presence in Singapore is often largely speculative and transactional in nature.

This is why the city-state is happy to offer a strictly regulated Employment Pass but may not be quite so eager to confer the status of a permanent resident on them.

And, let’s be honest, Mr Svanevik didn’t increase his chances, if he does decide to reapply after all (as many do, often for years), after openly decrying the bureaucracy and considering relocation, both for his company and his family.

Thanks for all the kind words and advice in DMs on this ?

— Alex Svanevik ? (@ASvanevik) October 14, 2024

I will not be re-applying for PR.

Having to ask bureaucrats to support your application, or to submit the same paperwork 10 times does not seem consistent with the values that Lee Kuan Yew founded this nation on.

I was… https://t.co/hCushUOxLc

By dismissing it so casually, he just gave ICA more evidence that he doesn’t really consider Singapore to be his permanent home after all.

Featured Image Credit: OPTO/ICA