House visits, walkabouts, posters on lamposts and the roaring cheers at rallies—these were the sights and sounds that I heard as a child during the election season.

But times have since changed. With the advancement of technology and the unexpected timing of the COVID-19 pandemic, Singapore had its first digital election in GE2020.

Not only did we see the absence of physical rallies, but GE2020 has brought a lot of attention to the impact of new media sources, from social media to podcasts, and many political figures have since leveraged these sources to reach new voters.

Meet the “new” media players

1. Instagram and TikTok

When it comes to new media, we cannot leave Instagram and TikTok out of the conversation, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic.

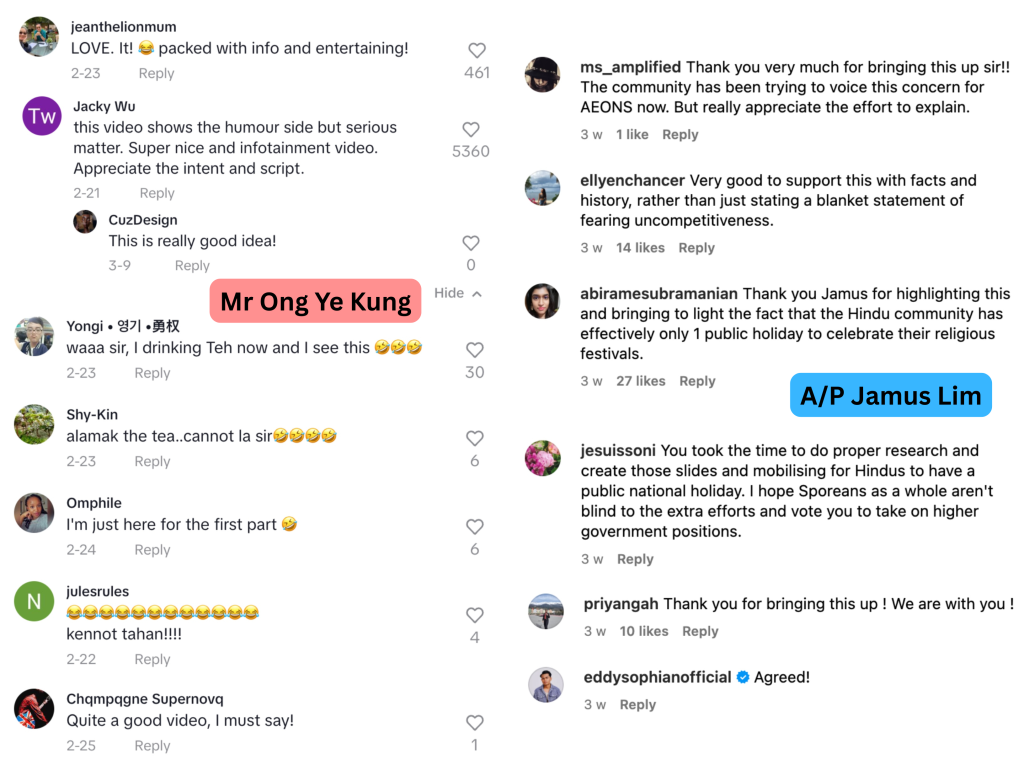

Whether they are in parliament or not, each political figure has their own “style” in interacting with their virtual audience while also educating them on public policies, including Singapore’s Minister of Health, Mr Ong Ye Kung.

@ongyekung Spilling the tea on why vaping is more toxic than it seems. ??

? original sound – Ye Kung Ong – Ye Kung Ong

Some political figures might be more active on Instagram, such as Associate Professor Jamus Lim of the Workers’ Party (WP), who is known for his carousel posts elaborating on his parliament speeches.

2. Podcasts

Many politicians have also made appearances on podcasts, with both the incumbent and opposition parties giving insights into their thoughts on the local political landscape.

Some notable podcasts known for their commentary on current affairs are The Daily Ketchup, Yah Lah BUT, and Teh Tarik With Walid.

Many use Instagram and TikTok to consume online content, but given that not everyone listens to podcasts, what draws politicians to them?

These videos often place politicians in an informal setting, where they engage in mostly casual banter with the hosts, while the audio format adds an “intimate layer” to the listeners’ experience—it’s like you are listening to a private chat that “fosters a sense of connection” that is challenging to replicate elsewhere.

Podcasts are more off-the-cuff, which allows the politicians’ personalities to really shine through and could make them seem more relatable if they know how to use the format well.

Dr Tracy Loh, senior lecturer of communications management at Singapore Management University responding to The Straits Times

One example could be seen with Singapore’s Prime Minister Lawrence Wong’s interview with The Daily Ketchup, where the self-proclaimed introvert shared how his life has changed since taking over from Mr Lee Hsien Loong, who is now the senior minister.

A double-edged sword

Some parties have emerged victorious in the social media game, and WP’s trailer for GE2020 often came to mind. Although the six-minute video didn’t have any dialogue, it went viral, to the extent that someone gave a commentary on the success of the video from a PR perspective.

Another politician who became a “social media darling” was Dr Tan Cheng Bock of the Progress Singapore Party (PSP), who became an “Instagram sensation” with his “hypebeast ah gong” persona.

Dr. Tan also remained one of the most followed opposition leaders on Instagram, with approximately 55,900 followers at the time of writing. But we’d have to admit, the “hypebeast” gimmick became old after a while.

Political Scientist Walid Jumblatt Bin Abdullah, who hosts the podcast Teh Tarik With Walid, shared that while politicians cannot avoid social media, they need to keep a balance between being light-hearted yet informative with their reach.

“There’s a fine line between being informative and cringe, and you need to balance that,” added the Associate Professor. He also highlighted that there are some politicians who just hop onto every TikTok trend and do them without any substance to it, though he did not mention any names.

If you just do that, then you think “oh this is a way to reach young voters!” I hope they lose. Because it’s so patronising to young voters to think that “oh just because i do this, young people are going to like me,” that’s not how voting works.

Associate Professor Walid Jumblatt Bin Abdullah on The Daily Ketchup podcast

However, we also know that nothing could be truly deleted from the Internet, and some politicians were called out for their past behaviour.

Ivan Lim underwent a “trial by Internet,” after he was introduced as one of the new candidates to contest for the former Jurong GRC under the People’s Action Party (PAP), where netizens accused him of having “poor character,” and a petition on change.org was created to campaign for his removal.

Mr Lim eventually released a press statement denying all allegations against him, but bowed out of the race three days later due to the online backlash.

Not long after, former WP member Raessah Khan was also placed in hot water for her social media posts that discussed race and religion, where she was investigated by the police after two police reports were submitted by members of the public.

With party leaders and then-teammates by her side, Miss Khan subsequently gave a public apology to the press, explaining that it wasn’t her intention to “create social division but to raise awareness (about) minority concerns.”

Finding a balance between reel and real life

With more people seeking out election content through alternative forms of media, there is no denying that it has become a useful weapon for any party to connect with the Singaporean electorate.

That said, politicians should not neglect interacting with their residents in their constituencies on the ground. After all, some people prefer to see what’s happening in the flesh, and that might play a part in casting their vote.

Check out our GE2025 microsite for the latest election-related news, find out which constituency you belong to, and more here.

Featured Image Credit: The Daily Ketchup, designed by Vulcan Post