“Nobody has a monopoly on good ideas”: PAP ministers on having more opposition voices in Parliament

Singaporeans will head to the polls this Saturday, May 3, in what may be the most unpredictable General Election in the nation’s history.

The ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), which has governed Singapore since independence, is facing a more competitive political landscape than ever before, with the opposition parties making steady gains in the last few elections.

In a livestreamed interview with The Daily Ketchup yesterday (April 30), PAP ministers Chan Chun Sing and Ong Ye Kung shared candid thoughts about the role of opposition in Parliament, and whether a more diverse political representation may be part of Singapore’s future.

Striking an “equilibrium”

Reflecting on the past five years with the increased number of elected opposition members in Parliament, Minister Ong acknowledged that the presence of opposition voices has influenced how policies are developed and debated.

“The fact that there is contestability—someone is there to voice out to say, ‘No, I disagree, I speak for a certain segment’—[makes you] a lot more careful. You take in a lot more views”

When putting up a statement, a motion, or a bill, the PAP also considers how opposition members might respond to legislative proposals. “You’ll be thinking, ‘What will the opposition say? What would be their perspective?’ And you try to take that in.”

But that’s not to say internal scrutiny within the PAP isn’t also robust. According to Minister Chan Chun Sing, backbenchers are also expected to challenge and debate with the front bench when necessary.

“When anyone puts up a policy proposal—whether it is [from] the PAP backbenches or the opposition—the frontbench has the responsibility to look at it very hard, very critically, and ask ourselves, ‘Does it work or not?'”

If there are good ideas from the opposition or [PAP’s] backbench, we will acknowledge it… because nobody has a monopoly on good ideas. All we want [are] good ideas for the country.

Minister Chan Chun Sing

That said, Minister Ong believes the ideal political model for Singapore lies in striking “an equilibrium”—where you have a strong ruling party that can be fast and decisive, but also a loyal opposition that provides checks and balances.

He noted that over the last parliamentary term, the opposition has not shied away from pushing back— sometimes even “quite fiercely”—on key issues.

“When they push back, sometimes there’s public resonance. So you know it cannot fly, even if you have the numbers,” he said.

At the same time, he also acknowledged the opposition’s conduct during moments of national crisis. “When it comes to a crisis, they never obstruct… they even speak up, which I appreciate.”

A “co-driver” to the government

But what is the right balance between strong governance and effective opposition to strike that equilibrium?

Minister Ong recalled a quote from the Workers’ Party that has resonated over the years. In 2011, then-WP chief Low Thia Khiang described the party as a “co-driver”—one that would serve as a check on the government in case “the driver drives off course or falls asleep.”

“I would say Singaporeans agree with that,” he said. “And it’s very hard to argue against it”

However, Minister Ong cautioned that if the opposition expands further, the role of the “co-driver” could shift.

“The co-driver [could also], let’s say, take on the role of a backseat driver and start giving you instructions,” he explained. “The driver can still take in all these inputs, [he’ll] still have his GPS, and [he’ll] still be in charge.”

But there will come a point when the co-driver goes beyond that—when he has “one hand on the steering wheel” and says, ‘I also want to drive.’

At that point, Minister Ong said that things could become “dangerous.” “You can crash, and then the co-driver will say, ‘Oh actually, I’m not the driver. If it crashes, it’s [PAP’s] responsibility.’”

If Singapore were to reach this point, he further added that the city-state would become uncoordinated. “Singapore would not only be small… but also indecisive [and] slow.”

This concern is echoed by Prime Minister Lawrence Wong, who has also cautioned in recent rallies that losing key PAP ministers to the opposition could weaken the government’s effectiveness.

Minister Chan Chun Sing also weighed in on the Workers’ Party stance, which clarified that it does not aim to form the government in this election—a position he described as “not very correct nor responsible.”

“When you go into a political contest and you say that these are your plans, you must really be prepared to make it happen,” he said, adding that such accountability is especially important at this stage of Singapore’s political development.

Nevertheless, Minister Chan emphasised that the government’s “first responsibility” is to Singaporeans. “It’s about whether we can build a system that can help our fellow Singaporeans.”

Every time there is a parliamentary debate, people raise various points, and it will help us sharpen various things. And this comes from the PAP backbenches as much as it can come from the opposition.

But what I really hope to see in Parliament is that we keep moving things forward so that we are in service of Singapore and Singaporeans.

Minister Chan Chun Sing

-//-

In the live stream, Minister Chan and Minister Ong also spoke about the GST increases, the impacts of the US tariffs, and what it means to be a political leader, among other topics. You can watch the full video here:

Check out our GE2025 microsite for the latest election-related news, find out which constituency you belong to, and who’s running where on the election battleground here.

Also Read: What will the next Parliament look like? Here are the most likely outcomes & distribution of seats.

Featured Image Credit: Screengrab from The Daily Ketchup

If you think that lowering the eligibility age for singles to BTO is good, think again

Disclaimer: Unless otherwise stated, any opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

In every Singaporean’s life, there comes a time when housing becomes a key concern. For couples, it’s not uncommon for the question: “Do you want to BTO together?” to actually mean “Will you marry me?”

Even for those without a partner, moving out and having your own space is part of what it means to be an adult as well.

Yet, for many young adults, the dream of getting your BTO has never been more difficult.

Over dinner the other night, a friend of mine worried that his BTO flat at Tanjong Rhu might be too close to the expressway and that the noise would be a problem, only to be shut down by another friend who hadn’t even gotten his BTO despite multiple applications: “Got flat good enough liao, you don’t want it, give me la!”

But they’re not alone. From complaints about long waiting times to frustration about oversubscribed projects, young Singaporeans have been airing their dissatisfaction with the system. Rentals are a hot topic as well, with a 2024 survey by PropertyGuru finding that most tenants considered rental prices too high.

It’s no surprise, then, that housing has become a campaign issue for many parties in this election. The Workers’ Party and Progress Singapore Party have both suggested lowering the minimum age for singles to buy BTO flats, while the Singapore People’s Party has suggested setting the threshold to 30.

In addition, the SPP is calling for the expansion of the Selective En Bloc Redevelopment Scheme to more estates, and the PSP is pushing for Singaporeans to be able to buy new flats without having to account for the cost of the land.

Evidently, housing is a huge talking point for this election—but do these policies actually help solve the problem?

The two facets of Singapore’s housing crisis

Firstly, it’s clear that there are two different problems that Singaporeans are complaining about.

The first is that there aren’t enough BTO flats in Singapore.

Projects like Central Trio @ AMK were oversubscribed by 7.9 times, while projects in Bedok and Kallang-Whampoa were oversubscribed by 4.9 and 4.4 times, respectively.

These numbers indicate that there is already fierce competition for BTO flats, and crucially, they reveal the ratio of couples seeking flats compared to the number of flats available.

If projects can be oversubscribed by seven to eight times, with some projects even oversubscribed by 14 times, it is no surprise that Singaporeans are taking issue with the scarcity of BTO flats.

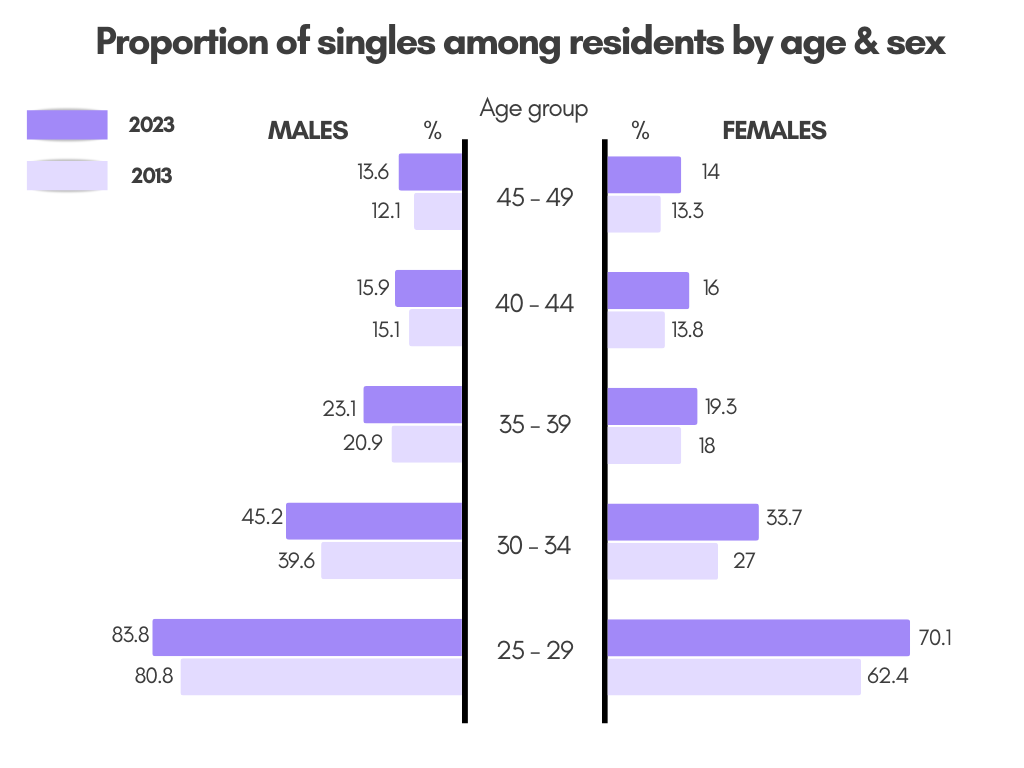

The second problem is the increasing number of single Singaporeans, who are also applying for BTOs and smaller flats.

These Singaporeans, however, can only apply for flats once they reach 35 years old, and even then, only for smaller flats.

Nevertheless, the increasing number of singles also means that the demand from this group of Singaporeans is not insignificant.

The two-room flexi flats that singles could apply for are also seeing massive oversubscription numbers, with projects at West BrickVille being 36 times oversubscribed and Tower Breeze being 29 times oversubscribed.

It’s no wonder that almost all policy proposals on housing centre on trying to alleviate the situation for singles, by allowing them to get flats at a younger age.

Yet, these policies also seem to be missing the forest for the trees. Trying to alleviate the high demand for the small number of flexi-flats is a good idea, but it should be viewed in the context of the larger market for flats in Singapore.

Not all flats are good flats

That being said, not all estates and BTO flats are equal. While there are oversubscribed projects, there are also undersubscribed projects that do not sell out because of their unpopularity.

Last October’s BTO exercise saw Taman Jurong Skyline in Jurong West being undersubscribed, due to its lack of MRT access.

Tengah is also another unpopular option, as the new estate lacked amenities.

What this means is that it’s not just purely a supply problem, but also somewhat a demand problem—namely that Singaporeans are picky about where they stay.

Consider then, what would happen when we lower the minimum age for singles to apply for a BTO flat. The demand for prime location flats, especially those in central locations and mature estates, will rise far more than the demand for flats in undersubscribed projects.

Are we really sure that that’s what we want for Singapore?

More people applying for the same number of houses means lower chances for everyone to get the flat that they want, and longer waiting times for applicants as they try again and again unsuccessfully.

Singles might get more chances at getting a flat, since they can start applying earlier, but this comes at the expense of families who are now competing with them for the same number of flats.

More applicants, more competition

By lowering the age at which singles can apply for BTO flats, we would basically be allowing for more people to apply for the same number of flats, when competition for the flats is already causing complaints and dissatisfaction.

Of course, that’s not to say that singles don’t deserve a flat, and that they should suck it up or keep renting indefinitely.

What I am saying is that simply lowering the eligibility requirements would likely heighten the competition for each flat, especially those in prime areas, and that this is not ideal.

Instead, what should be done is to redirect the demand for flats to non-prime areas. These areas are undersubscribed, which means that there are plenty of balance units to be sold. Each unit that remains unsold is potentially a flat that could be used to alleviate demand from the already oversubscribed projects in prime locations.

This is where the focus should be, rather than simply lowering the eligible age for singles to get flats.

Of course, that’s easier said than done. Singaporeans are picky, or they would have already chosen to apply for these projects. Young Singaporeans are used to having access to amenities like schools, public transport, and supermarkets.

These amenities are what mature estates have and non-mature estates do not. And while they do take time to build up, they are also essential to turning flats from being in ‘bad locations’ to being ‘good flats.’

In the meantime, renting out balance flats in non-mature estates can be a way to at least temporarily alleviate the demand for prime location flats. Rental tenants don’t expect to stay there forever, and so might be more willing to temporarily put up with the lack of amenities if there is a good reason, for example, lower rental costs.

Providing extra rentals would also mean lower rental prices across the board, as those who can accept living in non-mature estates move there from mature estates.

The government already runs the public rental scheme, intended for Singaporeans who have no other housing options. It might be a good opportunity to expand this scheme, albeit without the subsidies, since this new group of applicants would not be in the same financial position.

Demand for flats will be split between those who can accept staying in non-mature estates temporarily and those who really need a flat in mature estates. At the very least, this will give the government some extra time to develop and build new projects in mature estates, if absolutely necessary.

Singapore’s housing complaints are twofold: the first is that there aren’t enough ‘good’ flats going around, and the second is that Singaporeans who are single aren’t being given enough opportunities to get a place of their own.

The policies being proposed to lower the age at which singles can apply for flats can deal with the second problem, but it will likely run into the same issues as the first problem unless something is done to address the supply of ‘good’ flats as well.

Demand is only half of the equation when it comes to solving the housing woes that Singaporeans complain about. The far more important factor to deal with is supply, which, thus far, no one has made any real suggestions on.

- Read other articles we’ve written on Singapore’s current affairs here.

Also Read: Singapore at 60: How does it compare to when it was 50, 40, 30, 20 & 10? Here are the numbers.

Featured Image Credit: Derek Teo/ Shutterstock.com

What will the next Parliament look like? Here are the most likely outcomes & distribution of seats.

Disclaimer: Any opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

The Singapore General Election campaign ends today with the cooling-off day following tomorrow and the final vote on Saturday. I have commented on the electoral chances of candidates in specific constituencies in my articles published over the past few weeks, so in this final summary, let’s take a look at where it all leads.

What could the Singapore parliament look like on May 4? How many seats can the PAP win? How many electoral divisions can the opposition conquer? And how many parties will Singapore see in the parliament this term? Two? Three? Or maybe four?

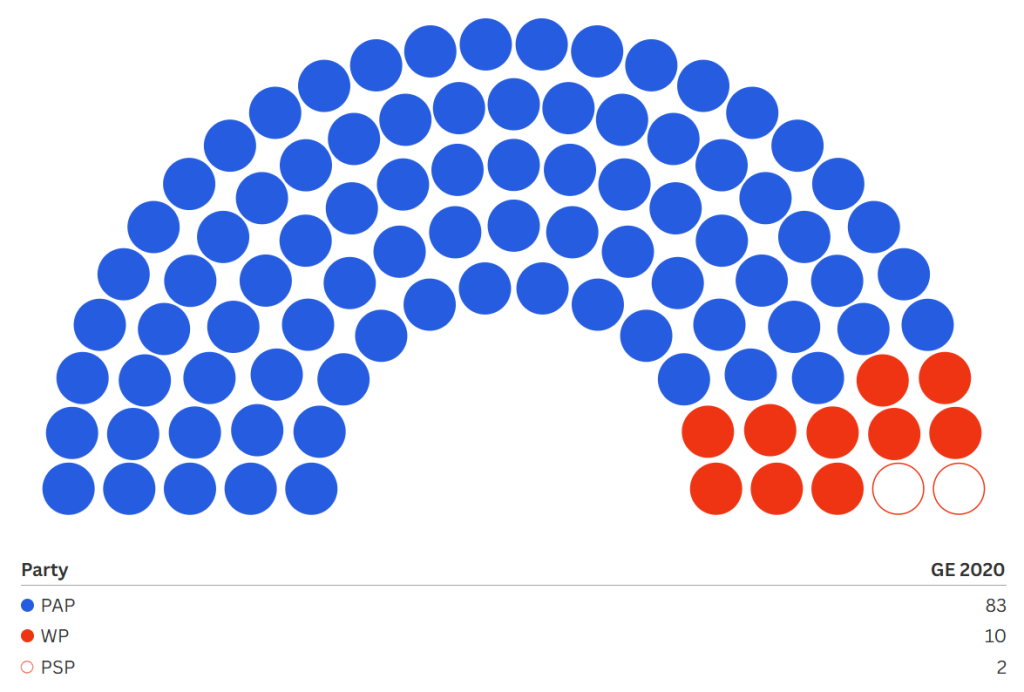

Here’s where we start, the result of the General Election in 2020:

83 seats for the PAP, 10 for the Workers’ Party and an additional two NCMPs from Progress Singapore Party of Tan Cheng Bock, for a total of 95 parliamentarians.

This year, 97 seats are up for grabs in the election, though the final number of MPs will depend on the distribution of any potential NCMP slots.

The following analysis is based on the assumption that there are no more than four parties that can realistically compete for seats in Singapore’s Parliament: PAP, WP, PSP and perhaps SDP. I do not want to dismiss other participants casually, but the electoral success of any other party or independent candidate would be a major surprise to everyone.

Battlegrounds

As usual, the People’s Action Party is fielding candidates in all 33 constituencies. Their biggest rivals from the Workers’ Party are contesting eight of them, including two which are considered to be their safe, core areas: Aljunied GRC (5-member GRC) and Hougang SMC.

Here are the remaining six, each being a battleground to watch:

- Sengkang GRC (defended by WP)

- Punggol GRC

- Tampines GRC

- East Coast GRC

- Tampines Changkat SMC

- Jalan Kayu SMC

In total, 20 seats are in contention in those electoral divisions.

PAP’s other major challenger is the Progress Singapore Party, which came very close to flipping West Coast GRC last time and received two NCMP seats in parliament for their effort.

This year, the party is contesting six constituencies, including two GRCs and four SMCs, with a total of 13 seats. Its best chance is, once again, in the West, under a redrawn West Coast-Jurong West GRC—though they should not be counted out in other locations either.

In 2020, they were just upstarts on the local political scene, but after five years in Parliament, with an outspoken current Secretary-General Leong Mun Wai, their brand as something more than just Tan Cheng Bock’s pet project could resonate with voters in other places too. Here’s the complete list:

- West Coast-Jurong West GRC

- Chua Chu Kang GRC

- Bukit Gombak SMC

- Kebun Baru SMC

- Marymount SMC

- Pioneer SMC

Finally, there’s the Singapore Democratic Party of Chee Soon Juan, which has been waiting nearly 30 years to return to Parliament after their complete defeat in 1997.

It is contesting four constituencies, two GRCs and two SMCs, with 11 seats. Realistically, however, the SMCs are the only two where they can hope to upset the PAP. Contesting Marsiling-Yew Tee and Sembawang GRCs against Lawrence Wong and Ong Ye Kung, respectively, is a tall order.

It’s no surprise, then, that Paul Tambyah and Chee Soon Juan chose more promising one-vs-one contests, as I explained before here. They’re running in:

- Bukit Panjang SMC

- Sembawang West SMC

where they won’t be facing any PAP ministers.

In total, this adds up to 35 seats that the opposition can compete for with the PAP, plus six already considered safe in the hands of the Workers’ Party.

Electoral scenarios

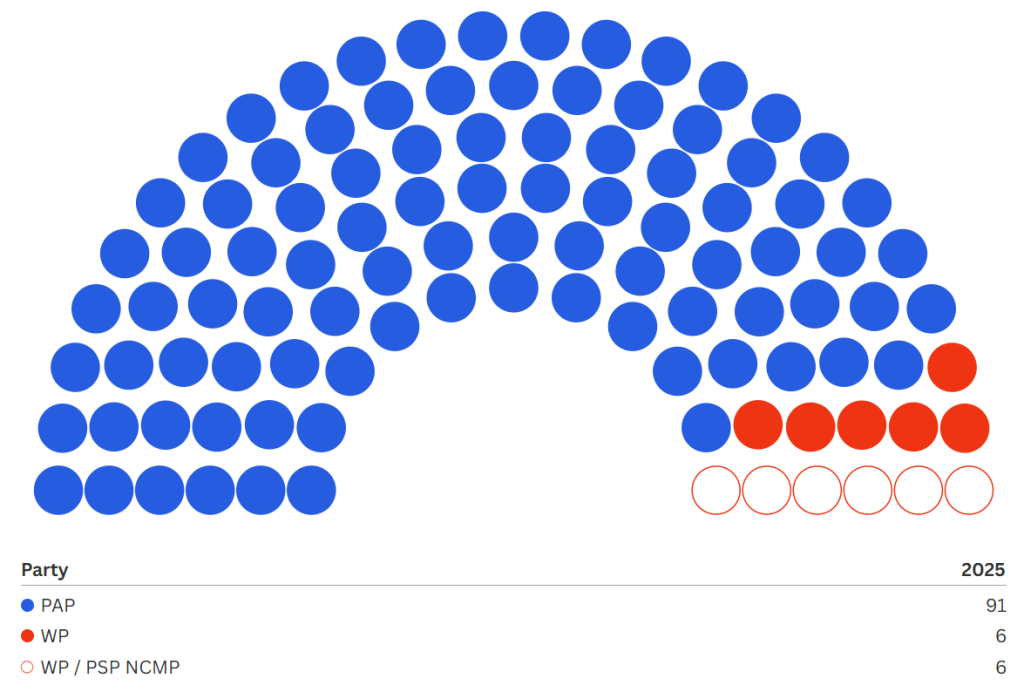

1. PAP retakes Sengkang, restores its position from 2015

A dream scenario for the ruling party, which isn’t without chances in Sengkang this year. If it wants to take it back then now is the time, otherwise it may become another long-term WP-hold.

PSP, weighed down by some of its own controversies from the past years, fails to flip the West Coast, and the Parliament sees a mix of very strong PAP and opposition divided in half into elected MPs and NCMPs

The parliament has 103 members as a result, given that the NCMP scheme guarantees a minimum of 12 opposition voices in the chamber.

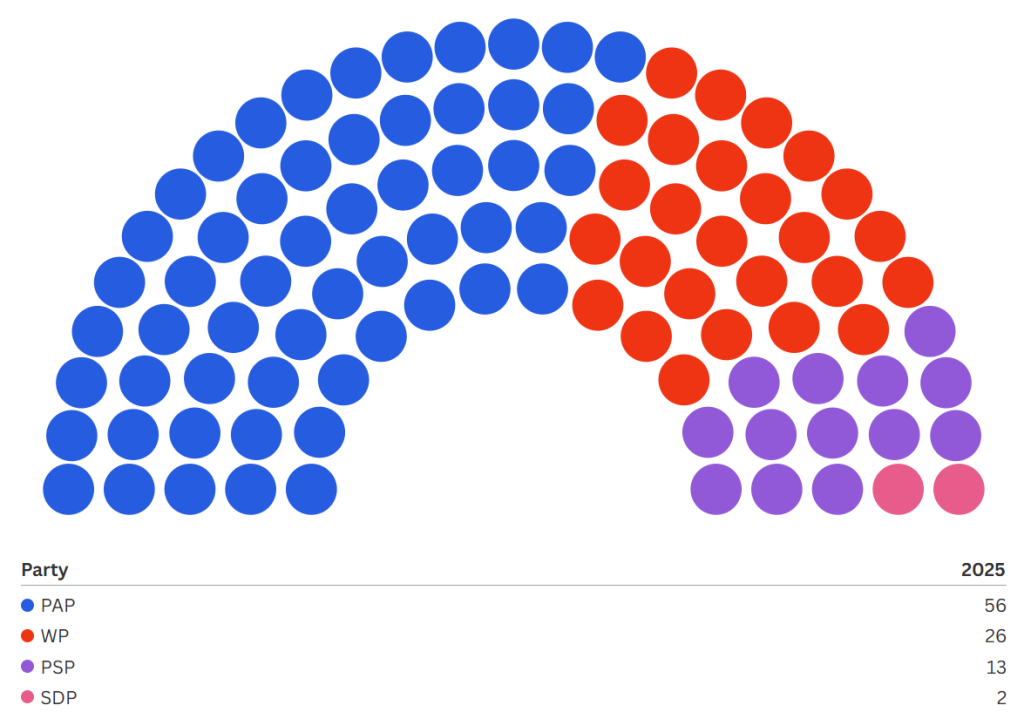

2. Opposition sweep: how would it look like?

We’ve looked at one end of the spectrum, now let’s look at the other—what would the Parliament look like if the opposition swept all of the seats it could even remotely contest? If WP and PSP win all of their constituencies, and SDP manages to put its two leaders in the Parliament too:

In a 97-member Parliament, PAP would still command a strong majority of 57% of all seats, but below the margin needed to occasionally amend the Constitution. Just like the first scenario was their dream outcome, this is their nightmare.

It isn’t very likely, but it is not outside of the realm of (remote) possibility.

3. Major opposition success

Now let’s consider some more realistic outcomes, starting with what is reasonably achievable by the opposition this year.

Workers’ Party is hoping to defend Sengkang and extend its winning streak by taking at least one other GRC or even two. Their SMC chances don’t look quite as good as their prospects for Punggol, Tampines and East Coast.

If they win two of these, they will grow their team by another nine or 10 MPs.

On the opposite side of the island, PSP hopes to finally win the West Coast, which would increase their presence in the Parliament to a full five members. This is an achievement well within their reach and one they have been preparing for.

Finally, to call the GE a success, the SDP would have to win at least one seat, given that the NCMP scheme would no longer be applicable.

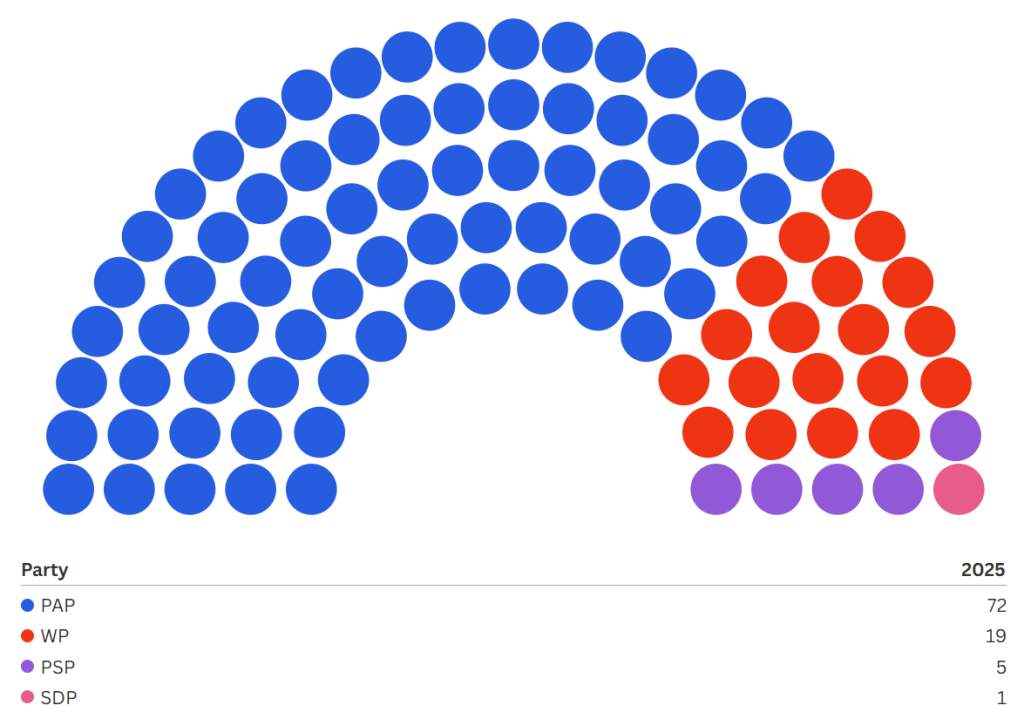

Here is what such a parliament would look like:

Such a result would, without doubt, be called a major success for the opposition. Adding three whole GRCs would end the NCMP scheme and their reliance on it.

And while difficult, it is not something that couldn’t be reasonably considered before the vote.

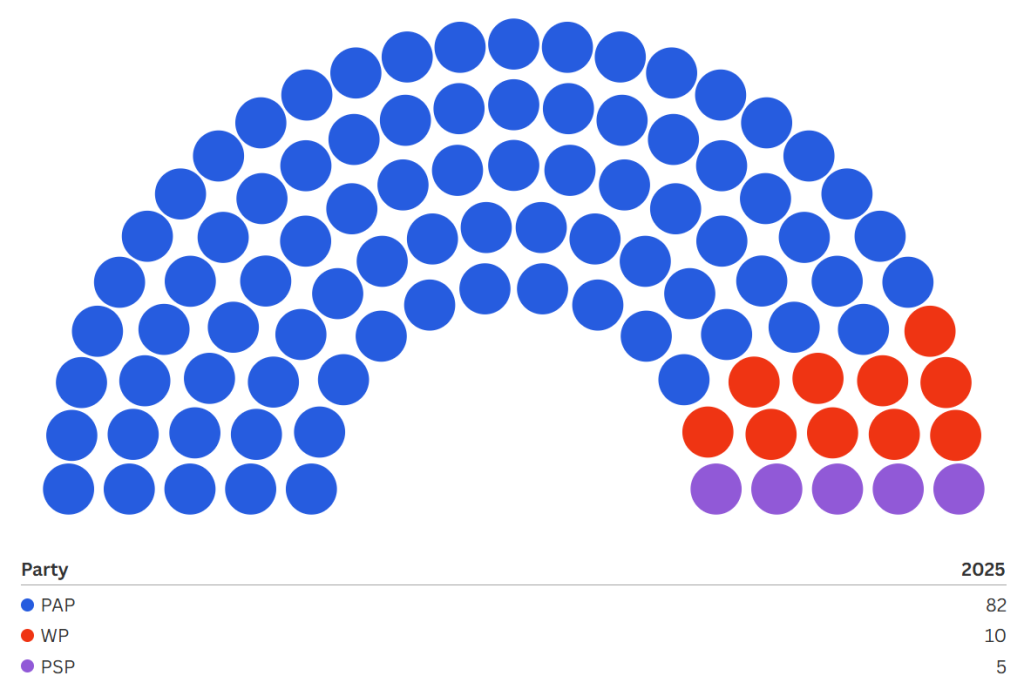

4. WP stumbles, PSP flips

A more conservative look at the chances of all participants, bearing in mind that the Workers’ Party has had its share of controversies both during the last parliamentary term, as well as during the ongoing campaign.

While it is able to put up a good fight in the constituencies contested, it’s not unlikely that it will stay where it is—controlling Aljunied, Hougang and keeping its Sengkang team as well.

Meanwhile, PAP’s West Coast GRC lineup, burdened by the fallout of the S Iswaran scandal, is vulnerable to PSP’s challenge, which the latter could turn into a victory, making it a solid second opposition party in the parliament, with half the seats that WP has.

Given the fact that the opposition’s progress has historically been quite slow, it would fit the pattern of them flipping one constituency at a time.

Among those ripe for the taking, West Coast-Jurong West GRC stands uniquely vulnerable, given the scandal involving the former anchor minister, which not even slightly modified boundaries may be enough to offset.

That said, PAP is not without chances, of course, as justice was meted out. Iswaran was sent to prison, and the second in command there, Desmond Lee, is a full minister too—and a young one, compared to the opposition team led by the 85-year-old Tan Cheng Bock and 66-year-old Leong Mun Wai.

Range of possible outcomes

Of course, we could slice and dice the chamber in any number of alternative ways, but these few examples are meant to illustrate the possibilities.

Another way to look at them is simply by the range of seats each party is most likely to contest successfully, under the same conditions I set in the beginning (they are, of course, my own, entirely subjective opinion):

People’s Action Party

Broad range: 57 to 91 seats

Reasonable range: 71 to 87 seats

The ruling party can hope to fight WP back in Sengkang and defeat all other opposition parties, including PSP in the West Coast. It’s their dream outcome, but not an unrealistic one given the past performance.

However, it could also lose as many as three to four GRCs. Besides the West Coast, Tampines and East Coast look vulnerable, and Punggol seems to be a close race too, although PAP might have an edge there with the DPM Gan Kim Yong and Sun Xueling duo.

Workers’ Party

Broad range: 6 to 26 seats

Reasonable range: 10 to 20 seats

The leading opposition party seems untouchable in Aljunied and Hougang. Defending Sengkang should also be doable, despite the Raeesah Khan scandal that left the constituency with an empty seat for the past four years.

On the other hand, it should offer PAP a strong challenge in other GRCs and could win one or two of them this year, depending on how people weigh the scandals that rocked both the government and the opposition in the past year.

Progress Singapore Party

Broad range: 0 to 13 seats

Reasonable range: 0 to 5 seats

PSP will be trying to prove itself this year after its narrow loss in 2020. However, while the party could resist the PAP in all of its constituencies, the only good chance it has at success is in its home division of West Coast.

If it fails to win it again, there’s still the consolation prize of NCMP seats, assuming the Workers’ Party doesn’t win any other constituencies.

Singapore Democratic Party

Broad range: 0 to 2 seats

Reasonable range: 0 to 1 seat

Finally, SDP might be contesting 11 seats, but all eyes are on Paul Tambyah and Chee Soon Juan. Both have their chances, but the relocation of the latter, after Bukit Batok SMC disappeared after the EBRC review, might undermine his chances.

Meanwhile, Paul Tambyah is back for a rematch in Bukit Panjang SMC, having lost by less than 7.5% in 2020, and it wouldn’t be a shock to anybody if he succeeded in his challenge this year.

SDP might not be the favourite in either of the races, but if it came out on top, no one could say they didn’t see it coming.

What do the results really mean in Singapore?

As you can see, the ruling party is still expected to hold a significant majority in the parliament, and their most capable rivals can only gather enough candidates to contest around 40 seats out of 97—realistically even fewer than that.

On the other hand, Singapore shouldn’t be evaluated by the same standards as any other democratic country. Here, a loss of a single constituency by the PAP is considered a major event and a warning signal sent to the government. In other words, it means a lot more than simple math would suggest.

This is why the government candidates have been campaigning quite intensively to secure the “strong mandate” for another five years, even though they are nearly certain to remain in charge.

At the end of the day, when the sun rises on May 4, the government will still be run by the PAP, but the scale of its victory is bound to influence its policies going forward.

Check out our GE2025 microsite for the latest election-related news, find out which constituency you belong to, and who’s running where on the election battleground here.

Also Read: Ong Ye Kung: Singapore must be decisive, but with checks & balances

Featured Image Credit: Shutterstock/ Workers’ Party/ Graphic designed by Vulcan Post