All doctors are haunted by the mistakes they made. Some fare better than others, some not.

I remember the various conversations we had, colleagues, friends, flatmates, most over meals, some with tears involved.

How can you not be, when a simple scrawl—your signature—could quite literally cause as much harm as good?

I don’t think anything quite prepares you for life as a doctor and the responsibility that comes with it.

I remember stepping out onto the ward for the very first time; it was meant to be the highlight, the epitome of medical school, what we all slogged for: the day when we become doctors!

Instead it was a day full of edginess—of course, I hear you remark, you’re saving lives! How can you not be?—but the nervousness wasn’t for the life-saving drama that Grey’s Anatomy portrays so well or the glamour of bringing someone back to life.

It was for ‘everyday’ decisions… ‘Everyday’ for a doctor that is.

Medicine is so far advanced now that we take over so much of normal physiology. Not drinking, we give you fluids through a drip directly into your veins. Are you diabetic? We give you insulin to help your body breakdown the sugar you consume.

For a baby doctor, this is where it all starts, the simple everyday stuff.

How much fluids should I prescribe? Too much intravenous fluids, could potentially send a patient into fluid overload with fluid accumulating in their lungs; too little fluid and you could potentially cause kidney damage.

Soon, all these become a ‘norm’.

We soon learn that the human body is an amazing thing, able compensate for the various insults we throw at it. Homeostasis, we call it.

Our bodies can hold surprisingly a large amount of water, maintaining a fine balance between the water that’s in the cells, bathing the cells and of course in the veins. It takes quite a lot to throw the balance awry in someone fit and healthy, not so for the extremes of ages.

And so we ‘get away’ with it, refining our skills as time passes on. But some things are less forgiving.

I remember the time when I had excised a skin cancer, but it had been incomplete. I had done it with supervision, and we had taken it all the way down to the nasal bones thinking we had gotten everything out.

We then did a ‘local’ flap and had advanced skin down from the forehead to cover the defect. 6 weeks later, my boss had the responsibility of breaking the news to the patient that the excision had been incomplete.

The logical thing would have been to ‘re-excise’ it, but it wasn’t so straightforward. The local flap meant that the tissues were distorted and it would have been difficult to be sure the few cells left could be re-excised, not to mention that the cosmetic result would be suboptimal.

The other options were radiotherapy or watch and wait. The patient opted for radiotherapy in the end. There is a 4% risk of incomplete excision, and each patient is warned that another procedure might always be on the cards but it didn’t make me feel any better.

I resolved then to be ‘braver’, to ‘cut out more’, but there’s always risks with that. What if in the ‘more’ you take out a nerve and paralyse the face? What if in the ‘more’ you aren’t able to close the wound?

You ‘live and learn’ they say. And so with time, experience is gained. Your mistakes guide your practice, making you a better doctor.

You learn the art of practicing medicine, gaining an arsenal of skills at which to deploy, knowing when you can have a bit more leeway in challenging the body’s physiological reserves.

You toughen up, learning to live with your shortcomings and your own mortality. Callousness occurs, knowingly or unknowingly. Some doctors lose their humanity more than others, perhaps consciously or unconsciously reflected in the choice of specialty they eventually choose.

I chose to go into plastic surgery, a specialty where I get the opportunity to reconstruct various defects of natural or human causes; something where I could see the results of my handiwork upfront, but also a specialty where death is an uncommon occurrence.

Some of my colleagues are doing palliative care, where dying is part of everyday life. Some are intensivists, where you could literally ‘play God’, deciding whether or not to prolong somebody’s life.

But underneath it all, whichever specialty we go into, we each have our own struggles with the responsibility which only gets greater as time progresses.

Fluid prescribing no longer fazes me, but I now have the responsibility for deciding if someone needs surgery.

Another colleague recently had the responsibility of giving advice that would most probably lead to the withdrawal of care for a patient; hardly a decision anyone would dream of making, yet we do on a daily basis.

Yes, support is available from senior colleagues but advice, you learn very quickly, is given based on your assessment of the patient. The skills you learnt in medical school.

Present the wrong findings, and you get suboptimal advice.

We, the seniors soon learn which juniors are safe, which are unsafe, which ones whose judgements can be trusted, which ones where it might be better to have a quick look yourself.

I’ll be honest and admit I can’t remember where I first heard of this theory, but it clearly impacted me enough that I still remember it.

Knowledge presents in 4 different areas, the known known, the known unknown, the unknown known and the unknown unknown.

Everybody knows what they know, everybody loves finding out that about the hidden skill (the unknown known), everybody groans at the known unknown (the textbook of knowledge awaiting for your devouring before the exams) but perhaps the most unnerving is the last category, for how can you learn what you don’t know that you don’t know?

Time and again the ‘miracle cures’ of today are the ‘curse’ of tomorrow and they certainly weren’t kidding when they said a career of ‘lifelong learning’.

But perhaps it is the fear of causing unnecessary harm that keeps you safe. So we laugh about our mistakes, our near misses, we commiserate when we lose a patient, we work through what could have been done better.

We back each other up knowing that facing the same situation, we might have done the exact same thing, trusting in the one that holds life and death.

For truly as doctors we can’t prevent death, we just try and push it back, a day at a time.

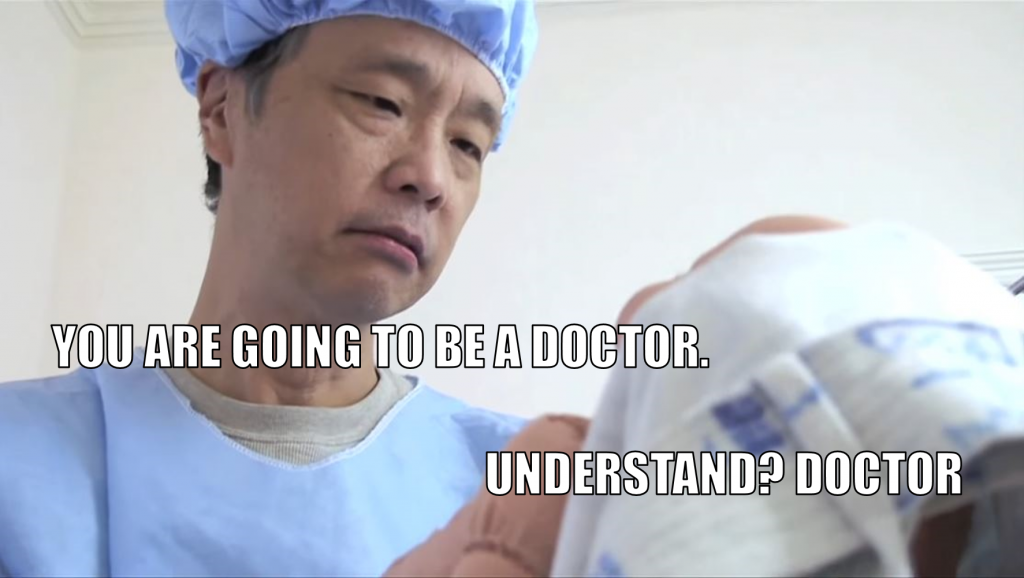

So parents, please don’t force your children into doing medicine.

Glamorous though it may seem, the hours are long, exams are always round the corner and are expensive, but above it all, it is people’s lives you’re gambling with—the very same people for whom your child will be responsible for.

Medicine is not for everyone.

This was written and contributed by L, a doctor who has always wondered why parents force their kids into medicine.

Feature Image Credit: Kevjumba YouTube channel