Last year, a group of 9 Malaysian students attempted to crowdfund their overseas education and ended up drawing a lot of flak.

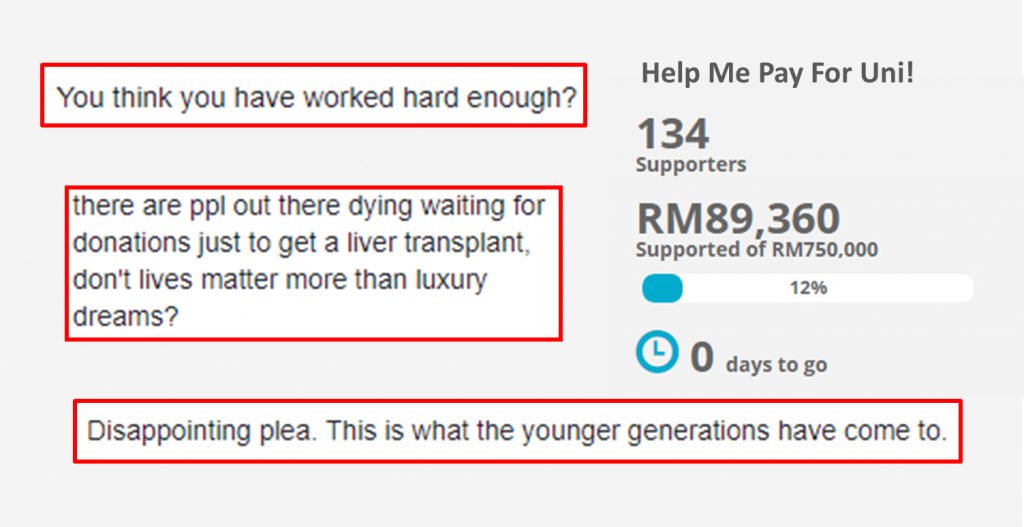

The comments ranged from how they were being too entitled by just asking and waiting for money, whereas others questioned the need to go to a university overseas in the first place.

More recently, we came across another crowdfunding attempt, this time by a dental student in IMU.

[Update: The crowdfunding page has since been taken down.]

The student did provide a long write-up in the crowdfunding bio, but in its essence, her main reason for wanting to go overseas is, “I believe that being abroad especially at this stage of my life is the best option for me as it aligns with my goals and plans for the future.”

From a quick Facebook search of the posts and shares, the comments have mostly been positive, with many users expressing support.

However, there were quite a few who raised doubts, and there is a growing thread of comments on her crowdfunding page too. Many of them question the crowdfunding attempt.

According to those commenters, if she already had the means to complete her education locally, is it necessary to pursue her studies overseas, particularly through crowdfunding?

That was a similar sentiment that dogged the nine students last year, who ended up only raising 12% of their RM750,000 goal.

This got us thinking though.

Are Malaysians really so unsupportive of students looking to crowdfund their studies?

On SkolaFund, a Malaysian website that is specifically for students to crowdfund for studies, there are 69 campaigns listed as “Ended”.

A quick search tells us that out of the 69 listed, only 8 were unsuccessful, in that they did not reach their target funding. However, we also noticed that one of the unsuccessful girls actually had a second entry where she raised 101% of her goal.

This proves that there are Malaysians out there who are happy and more than willing to contribute towards crowdfunding for education.

Are they only supporting those who choose to study locally?

Not the case at all.

On SkolaFund again, we found another girl, who also successfully hit her target to fund her overseas exchange.

So why didn’t the two cases highlighted at the beginning of the article garner such support?

It’s possible that the medium they used to crowdfund could have played a part. On SkolaFund, assurances are given, such as verifying every campaign before launch, and they transfer the tuition fee directly to university.

There are also clear breakdowns of exactly how those funds will be used.

Is it because the fundraisers are asking for an amount that is exorbitantly high?

It could be that the amount asked for turned off potential donors, even if they were thinking of contributing a portion.

What we noticed is, the JPA scholars and the dentistry student asked for amounts that ranged from RM350,000 to RM750,000.

Is it an unreasonable amount? Not quite. That is the cost of education overseas these days. Albeit it is still a considerably high sum of money.

However, in contrast, the SkolaFund requests are capped at RM10,000, which seems like a much more “reasonable” request.

Something else the comments brought up was the issue of giving back.

How would these crowdfunded students eventually contribute back to society?

The 9 students did say they planned to volunteer and give their time after returning, but they left out specifics.

In comparison, here’s a writeup from a student currently trying to raise money on SkolaFund.

There is also the question of accountability.

Who is to know for sure that these students are going to “give back” as they promised?

I don’t doubt that Malaysians are generous with both their time and money when they feel the cause is right.

And that might just be the clincher—some Malaysians don’t feel like they should be contributing the education crowdfunding when there are more needs out there that are more desperate and should be addressed first.

Crowdfunding for education in itself has been done for quite a while overseas. Several different models are now present, including one where the fundee pays back the donors by giving them a cut of their income once they’ve graduated.

This is more similar to taking a loan instead. Loans do come with certain conditions and qualifications too, so this could be an additional option for students who are unable to get the loans.

From what we can tell, we don’t have a platform that uses this loan-like model yet in Malaysia.

Perhaps Malaysians might find it easier to accept that model seeing as it is somewhat a form of an investment. Famed business magnate and investor Warren Buffett has been quoted saying he would pay USD$100,000 for 10% of a student’s future earnings.

But for now, it’s clear that a vocal group in Malaysia would rather channel their funds elsewhere instead of an education crowdfunding initiative.