Back in the early 2000s, NASA-funded scientists conducted an investigation into alternative protein sources to offer astronauts more palatable options on long space journeys.

The result? Lab-grown goldfish meat that “looked and smelled” exactly like fish.

The scientists didn’t go as far as tasting it, though. The cultivated meat hadn’t yet been certified as safe to eat, and concerns lingered about potential infectious agents from the foetal bovine serum used to grow it.

Fast forward to 2013, the cultivated meat industry saw another breakthrough after years of research when Dutch scientist Mark Post announced he had created the world’s first cultivated beef burger. The cultivated patty, which was painstakingly grown strand by strand in hundreds of plastic dishes, took two years to develop and cost a whopping US$332,000.

This breakthrough sparked a wave of enthusiasm in the sector: startups emerged, making bold proclamations and laying out aggressive product timelines. Investors too, fuelled by the promise and potential of this new innovation, poured millions of dollars into cultivated meat ventures.

In 2021, investment in cultivated meat companies topped US$1.36 billion, growing by over 300 per cent from the previous year. Among these companies is Californian firm Eat Just, one of the top funded startups in the industry, having raised around US$850 million since its founding in 2011.

Eat Just was also the first company in the world to gain approval to sell its lab-grown chicken nuggets to consumers in Singapore three years ago to much fanfare.

But despite cinching regulatory approval and having millions of dollars poured into the industry, lab-grown meat has yet to make its way onto grocery store shelves.

For years, companies have promised that commercially-viable lab-grown meat was right around the corner, however, repeated missed product launches and setbacks have eroded investor confidence in the space. From 2022 to 2023, total investment in the cultivated meat industry dipped by 78 per cent, from US$807 million to US$177 million.

And as funding dries up, cracks in the industry are becoming more apparent, with MIT Technology Review dubbing lab-grown meat as one of the “worst technology failures” of 2023.

How did an industry which once held so much promise falter so quickly?

Another expensive Silicon Valley mistake

At its current state, the cultivated meat industry is propped up more by wishful thinking than science.

Sure, the most basic part of the process, which involves growing a few living cells into many, is not new—pharmaceutical companies have routinely cultured animal cells at scale for decades for antibody and vaccine production, and the first vaccine developed for human use was made from duck embryonic cells.

However, this process typically produces undifferentiated cell biomass. To turn this into something edible, you’d have to blend it with plant-based ingredients, or alternatively, you could attempt something vastly more difficult: getting the animal cells to form into muscle-like tissue.

The former will limit you to the production of “minced” products, like chicken nuggets and meatballs, while the latter will enable you to create fully-structured meat, such as fillets and steaks. But even when it comes to the creation of processed, “minced” products, many startups have faltered—none have managed to achieve affordability and scalability to date.

Take Singapore food tech darling Shiok Meats, for instance. When the company showcased its first prototype in 2019—the world’s first cell-based siew mai—it was quickly shoved into the media spotlight, heralded as one of the up and coming food tech startups in both Singapore and Southeast Asia.

The company’s offerings were scheduled for commercial launch in 2023, but there was just one problem: the five shrimp dumplings it showcased had a whopping S$8,000 to S$10,000 price tag on them.

Shiok Meats eventually did manage to lower costs by swapping some of the pharmaceutical-grade ingredients used in the production of their cultivated shrimp (which accounted for 90 per cent of its price) for plant-based and edible ingredients two years later, but even then, its products still remained relatively expensive.

A kilogram of lab-grown shrimp meat now set the company back by S$5,000, bringing down the cost of each siew mai to S$150, and the company’s co-founder, Sandhya Sriram, was so sure that this could be further reduced to a “two- to three-digit number” by the start of 2021.

But that never happened. In 2023, Sandhya came out to share on LinkedIn that Shiok Meats was “unable to scale its crustacean stem cells into production” after facing allegations that its core technology did not work and losing half its staff six months prior.

Production pauses, contaminated cell lines, and failed experiments

Shiok Meats’ struggle to scale isn’t an isolated incident; it’s a reflection of broader industry-wide shortcomings.

Earlier this month, The Straits Times (ST) reported that the production of Eat Just’s cell-based meat, sold under the label Good Meat, had been put on pause. Its S$61 million Good Meat production facility in Bedok, which was initially slated to open in the third quarter of 2023, also appeared to be shuttered.

When Vulcan Post reached out to Eat Just regarding the pause in production, an Eat Just spokeswoman was quick to clarify that the company’s production in Singapore “had never been continuous”.

Eat Just’s production has always been more campaign style—our regular cadence since we began production in 2020 has been to produce and pause, produce and pause. There’s truly no news here; we are simply in a paused phase of production as we have been in the past, and we plan to resume production and service to consumers very soon.

– An Eat Just spokeswoman on the company’s reported pause in production

Even if that may be true, the lab grown meat company has had a history of encountering setbacks in its cultivated meat experiments.

Sometime in 2018, when Eat Just was exploring cell-based duck products like foie gras and duck chorizo, scientists ran a scan on the cells being used and found mouse cells, forcing Eat Just to scrap its duck products altogether.

Temasek-backed Upside Foods also found similar contaminants—rat cells, to be precise—in their cell lines back in 2019.

The company has made progress since the incident, opening a production factory to scale its offerings, but an article by MIT Technology Review in 2023 alleged that Upside Foods was still producing its textured chicken product by growing thin layers of chicken skin cells in laboratory flasks, which are then manually pressed into chicken pieces—versus growing the chicken breast products in their bioreactors.

Is cultivated meat truly environmentally friendly?

Looking at the state of the industry, it’s painfully obvious that the technology isn’t at all there yet—it just seems more like a story about optimism. What should’ve been left in academia has now seemingly turned into a waste of time and resources.

Yet, many of these companies still chase the idea that these cell-based meats are viable and ethical alternatives to slaughtering animals.

Beyond the ethical allure of lab-grown meat, it is often hailed as a sustainable alternative to raising livestock. Feeding animals on farms requires a lot of land and energy, both of which can produce carbon dioxide emissions. On a global average, one kilogram of beef can account for emissions roughly equivalent to 100 kilograms of carbon dioxide.

Cultivated meat could potentially eliminate these environmental challenges as it requires less land, water and greenhouse gases. But according to researchers at the University of California, whether or not cultivated meat can deliver on its big climate promises still remains questionable.

In fact, they found the environmental impact of lab-grown meat to be “orders of magnitude” higher than retail beef based on current and near-term production methods.

This is because energy is required to run the reactors that house cultivated cells as they grow, which will likely involve the use of fossil fuels.

Sure, they could be replaced with renewables once they become widely available, but even then, the reactors, pipes, and other necessary equipment for production facilities often have associated emissions that are tough to eliminate entirely. In addition, animal cells need to be fed and cared for, and the supply chain involved in that also comes with emissions attached.

Cultivated meat production can benefit Singapore’s economy

But be that as it may, Singapore still stands to reap significant economic benefits from lab-grown meat.

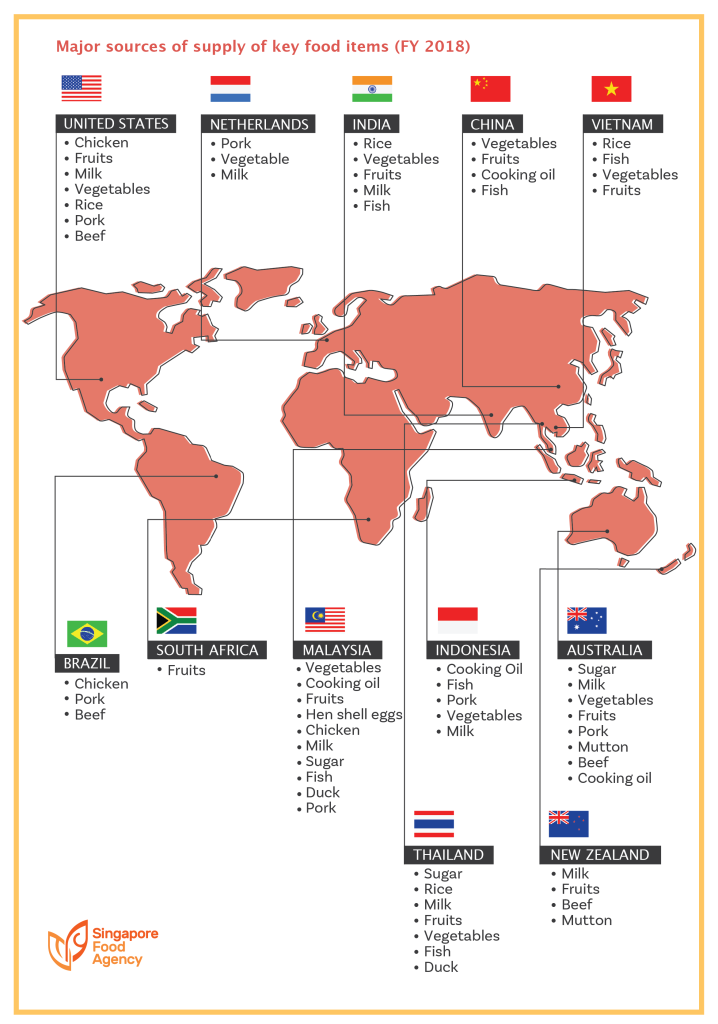

Given the nation’s land scarcity, cultivated meat could play a pivotal role in reducing the reliance on imported meat and address supply chain vulnerabilities. Presently, Singapore imports more than 90 per cent of its food from more than 180 countries and regions.

Although the government is working towards ramping up local food production to meet 30 per cent of the nation’s nutritional needs by 2030—up from less than 10 per cent currently—it falls short, especially when you consider that global demand for food is projected to increase by 50 per cent come 2050 with population growth.

Apart from this, with countries increasingly looking inwards and prioritising their needs over international trade following COVID-19, inflation and international security threats, deglobalisation poses additional challenges to Singapore’s food security, making investments in cultivated meat production even more strategically significant for the city-state’s economic resilience.

But these investments may never gain fruition, considering the current state of the industry.

Featured Image Credit: Lehigh University